On March 22, 1966, American climber John Harlin fell 1,000m to his death on the Eiger’s North Face. He was just 600m from completing his ambitious Direttissima route. Fifty-nine years later, we look back at his career, marked by innovation and a deep connection to the Alps.

From fine arts to pilot

John Elvis Harlin II was born in Kansas City on June 30, 1935. He graduated from Sequoia High School in California and later attended Stanford University, majoring in fine arts and dress design. In the early 1950s, Harlin began climbing.

Later, he joined the U.S. Air Force where he trained as a pilot, flying jet-fighter bombers.

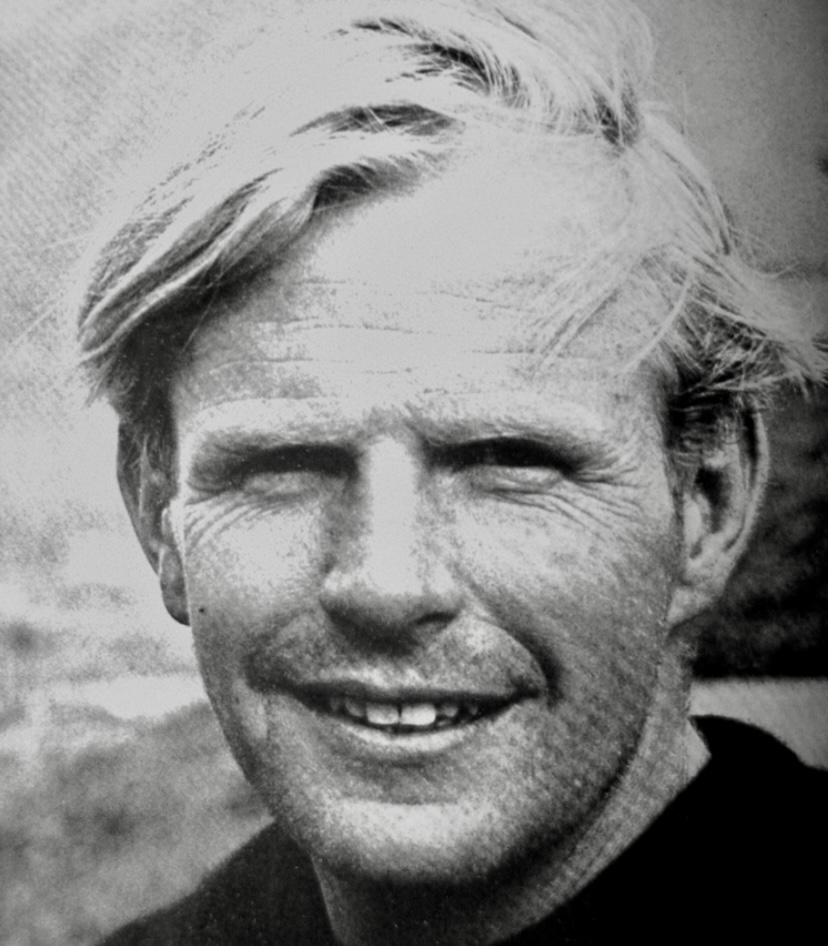

John Harlin. Photo: John Harlin III

During his Air Force service, Harlin was stationed in Europe. In 1954, he made his first trip to the Alps. Just 19, it marked a turning point in his life. That year, he attempted the Eiger North Face by the Heckmair route but didn’t succeed. The climb began a lifelong obsession with the peak.

He married Marilyn Harlin, and they had two children: son John Harlin III and daughter Andrea Harlin. In the early 1960s, the family moved to Switzerland and Harlin immersed himself in the alpine climbing community.

John Harlin and his family in Switzerland. Photo: John Harlin III

First American to climb the Eiger North Face

In the summer of 1962, Harlin became the first American to climb the North Face of the Eiger. He ascended via the 1938 Hechmair Route with German climbing partner Konrad Kirch. The climb took several days and required exceptional skill and endurance.

The same year, Harlin attempted the central Pillar of Freney in the Mont Blanc Massif, a steep granite route first climbed by Chris Bonington’s team in 1961.

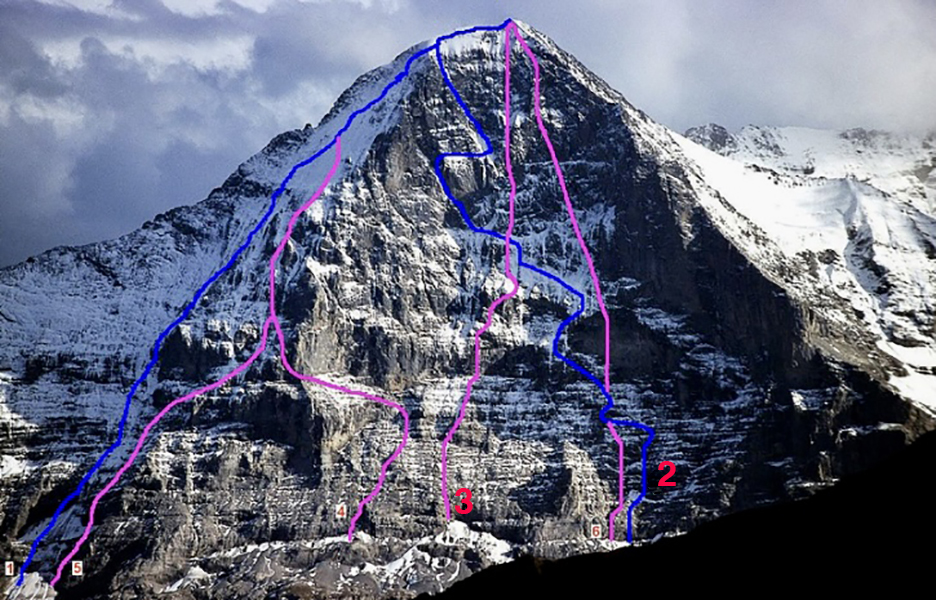

The North Face of the Eiger. Photo: Wikimedia

Other notable climbs in the Alps

In 1963, alongside American climbers Gary Hemming, Tom Frost, and Stewart Fulton, Harlin made the first ascent of the South Face of the Aiguille du Fou in the Mont Blanc massif. This climb was a technical masterpiece, involving steep rock and ice.

In 1964, Harlin, Chris Bonington, and Rusty Baillie climbed the northeast ridge of Cime de l’Est in the Dents du Midi in the Valais region of Switzerland.

In 1965, Harlin and Royal Robbins made the first ascent of the American Direct route on the West Face of the Aiguille du Dru, a steep and committed line that demanded advanced rock and ice skills.

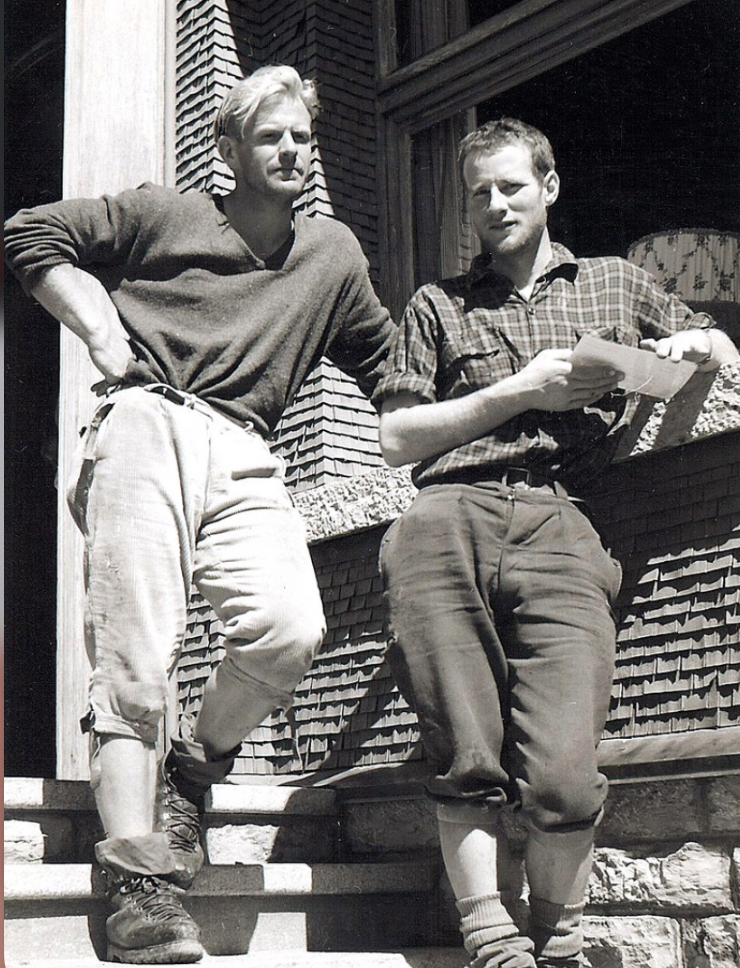

The Aiguille du Fou team. From left to right: John Harlin II, Tom Frost, Gary Hemming, and Stewart Fulton. Photo: Wikimedia

In June 1963, Harlin became the Director of Sports at the American School in Leysin, Switzerland. He also founded the International School of Modern Mountaineering.

Locally, Harlin earned the nickname Blond God. He was an excellent athlete, a member of the all-American Services football team, and, when younger, the junior wrestling champion of California.

Return to the Eiger

In the 1930s, many viewed the Eiger North Face as a crazy objective.

“The forcing of the Eigerwand [North Face] is principally a matter of luck, at least 90% of the latter is required,” Dr. Hug, a Swiss member of the Alpine Club, said at the time. “Extreme forms of technical development, a fanatical disregard of death, staying power, and bodily toughness are, in this case, details of merely secondary importance.”

Colonel Strutt, the retiring President of the Alpine Club, agreed. “The Eigerwand continues to be an obsession for the mentally deranged of almost every nation. He who first succeeds may rest assured that he has accomplished the most imbecile variant since mountaineering first began,” Strutt said in his farewell address.

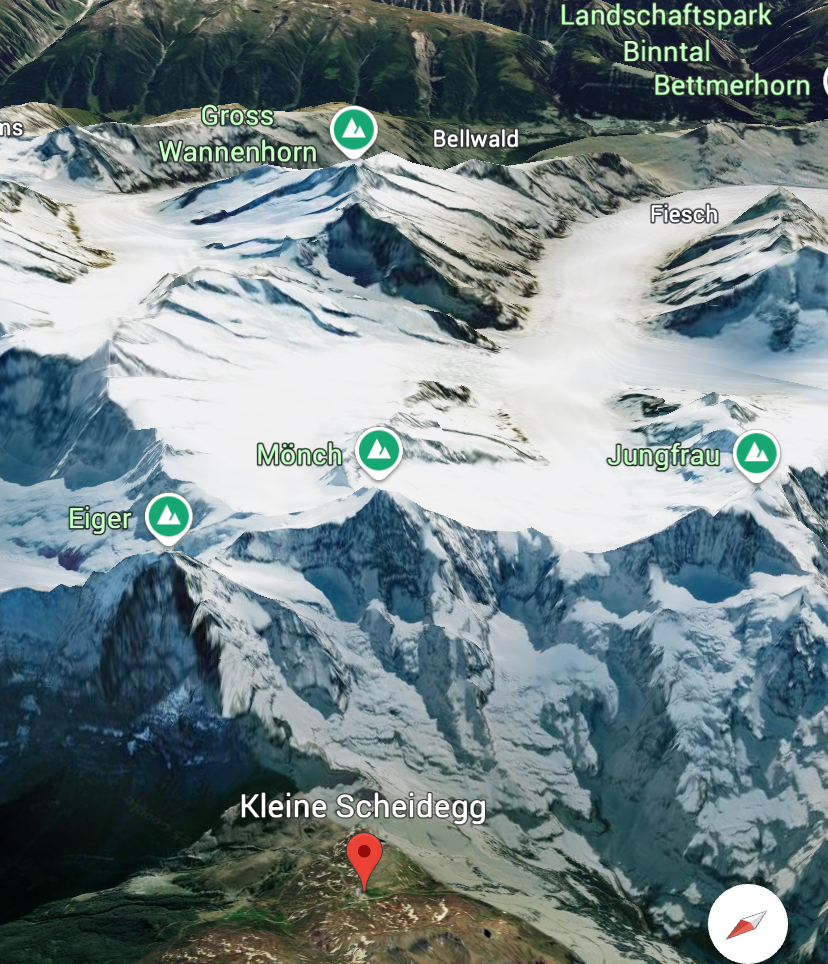

The North Face of Eiger from Kleine Scheidegg. Photo: Philippe Gatta

The North Face of the Eiger, rising 1,800m from its base to the summit at 3,967m, is notorious for its steepness, loose rock, and deadly weather. But it was finally ascended for the first time in 1938 by a four-man team that included Anderl Heckmair and Ludwig Vorg from Germany and Heinrich Harrer and Fritz Kasparek from Austria. The Heckmair route features ice fields, rock bands, and high exposure.

A German-Austrian party that included Toni Hiebeler, Walter Almberger, Anderl Mannhardt, and Toni Kinshofer made the first winter ascent of the Heckmair route in March 1961.

One year after his initial ascent of Eiger’s North Face in 1962, Harlin started to think about a direct line up the face.

John Harlin, left, and Konrad Kirch after the successful ascent of the North Face of Eiger in 1962. Photo: John Harlin III Collection

The team

Harlin made several reconnaissance climbs on the North Face. Finally, in February 1966, he organized a strong team. The group featured Colorado rock specialist Layton Kor (famed for his big-wall climbs in Yosemite), Scotsman Dougal Haston (known for Scottish winter ascents and prior Eiger climbs), experienced UK alpinist Chris Bonington, and Don Whillans in support. Don Whillans later withdrew from the expedition after a disagreement with the team.

In early February, Harlin’s party headed to Kleine Scheidegg, where journalist Peter Gillman would report on the ascent.

John Harlin in Grindelwald, Switzerland, in 1960. Photo: John Harlin III

There had been rumors that a German team had their eyes on the same objective. At Kleine Scheidegg, it became clear that the teams would be rivals, with both keen to be the first to finish a direct line on the North Face.

The German team included leader Jorg Lehne, Gunter Strobel, Klaus Huba, Sigi Hupfauer, Karl Golikow, Rolf Rosenzopf, Gunther Schnaidt, and Peter Haag.

Harlin’s party aimed for an alpine-style dash, weather permitting, while the Germans planned a relentless ascent with fixed ropes, regardless of conditions.

The route marked with the number 2 is The Heckmair Route. Number 3 shows the Harlin Direct route. Photo: Wikimedia

Starting the climb

Both teams began on Feb. 2, 1966, establishing base camps near Kleine Scheidegg.

The Germans fixed ropes systematically and advanced higher each day. Harlin’s smaller team pushed when the weather allowed, often climbing parallel to the Germans.

Both teams faced brutal winter storms, sub-zero temperatures, and frequent snowfall. Additionally, there was the danger from the North Face itself, offering exposure to rockfall and avalanches.

By mid-March, both parties had fixed ropes up to around 3,400m. Around March 15, after weeks of rivalry, the teams began sharing ropes and bivouac sites, prompted by harsh conditions and mutual respect. Harlin and Lehne negotiated a loose alliance, though separate summit pushes remained the goal.

Kleine Scheidegg near the Eiger. Photo: Google Earth

The fall

On March 22 at around 10:00 am, Harlin was ascending a fixed rope alone. He was on his way to join the others, approximately 610m below the summit, at 3,360m. But the 7mm rope snapped, likely because of wear, ice damage, or rockfall. Gillman, who was at Kleine Scheidegg watching the climbers with a telescope, saw Harlin fall 1,000m to his death.

The British-American team was devastated. Kor descended soon after, effectively leaving the climb. Haston and Bonington stayed, determined to finish.

The Germans, higher on the face when the accident occurred, learned of Harlin’s death by radio and offered support. The tragedy catalyzed a full merger of the two teams, and they would now go for the summit together.

Kleine Scheidegg. Photo: Hideo Obayashi

The John Harlin Direct

On March 25 at 2:30 pm, Haston, Lehne, Strobel, Hupfauer, and Huba reached the summit after a final 200m push. A storm hit the mountain after they summited, forcing a grueling descent via the West Flank, completed over two days.

The climbers, some suffering serious frostbite, named the line The John Harlin Route.

“When John Harlin fell to his death from the Eiger on March 22, 1966, the world of mountaineering lost one of its brightest stars. In the not quite thirty-one years of his life, Harlin had forged a career that was unique in ambition and achievement,” James Ramsey Ullman wrote in the American Alpine Journal.

For further details on Harlin and the 1966 climb, we recommend reading Eiger Direct by Peter Gillman and Dougal Haston.

John Harlin. Photo: Toni Hiebeler