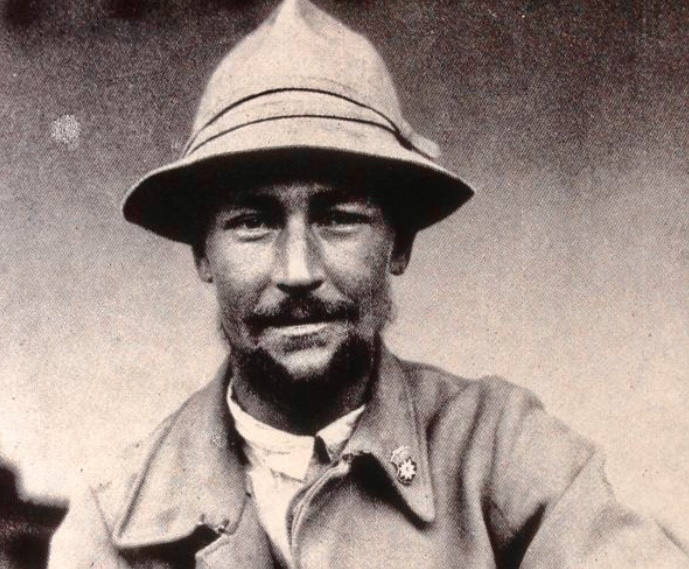

Peter Aufschnaiter was an Austrian climber who lived an adventurous, varied life, including turning a prison escape into seven years in Lhasa. To the general public, he is most familiar as Brad Pitt’s sidekick in Seven Years in Tibet, the Hollywood adaptation of Heinrich Harrer’s book. But Aufschnaiter was more than the soft-spoken guy with the Tibetan wife; in fact, that romance never happened. On his birthday, we revisit his life and mountaineering career.

Aufschnaiter was born on November 2, 1899, in Kitzbühel, Austria, where he began climbing before attending school. His family ran a small hotel, and his early exposure to the Tyrolean Alps sparked a lifelong passion for mountaineering.

He learned to draw maps and studied agronomy at the University of Munich, graduating in 1925. His diploma focused on irrigation systems for alpine agriculture.

Kitzbuheler Horn from the northwest. Grosses Wiesbachhorn is in the background. Photo: Thomas Laiminger

In 1929, Aufschnaiter joined a German-Austrian expedition to 8,586m Kangchenjunga. Led by Paul Bauer, the team climbed without supplemental oxygen. Aufschnaiter helped set up ropes and take precise altimeter readings while documenting the route. Bad weather finally stopped the party at 7,400m.

Two years later, Aufschnaiter returned to Kangchenjunga with a German expedition, again led by Bauer. Once again, they climbed without bottled oxygen but turned around at 7,940m in poor conditions. The expedition lost four of its members: Hermann Schaller and Pasang Sherpa died in an avalanche at 6,100m, and Sherpas Babu Lall and Lobsang succumbed to illness (non-AMS).

The upper section of Nanga Parbat. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

From Nanga Parbat explorer to war prisoner

In 1939, Aufschnaiter led a small team to 8,126m Nanga Parbat. Aufschnaiter, Heinrich Harrer, Hans Lobenhoffer, and Ludwig Chicken (no kidding) wanted to find a safe route for a climb the next year. The team set up a camp at 4,200m on the Diamir Glacier. They tried the West Face but had to abort due to rockfall and avalanche danger.

They then moved to a middle rocky ridge (the Aufschnaiter Rib) and put up 1,200m of rope, reaching 6,096m. The route then broke into loose stones and led only to a lower summit at 7,785m. Aufschnaiter took photos and left tools for the next trip. This reconnaissance was part of a broader German effort on Nanga Parbat, and Aufschnaiter’s detailed photographic and topographic records were important.

The team left the mountain on Aug. 28, 1939. Three days later, on September 1, Germany started World War II. The mountaineers reached the port of Karachi on September 5, where British police put them in handcuffs.

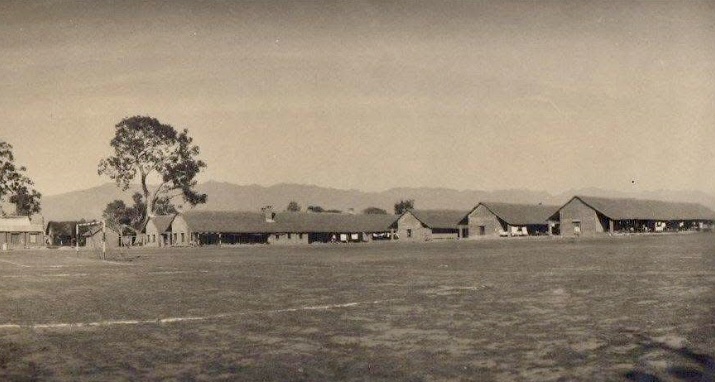

The prison camp at Dehra Dun was 400km north of Delhi. Wire fences held 1,200 people from Germany and Austria. Conditions were relatively good, with guards letting prisoners play sports and read books, but escapes were harshly punished. Aufschnaiter used the time to study the Tibetan language.

The prison camp at Dehra Dun. Photo: BTDT Archives

Escape

Aufschnaiter started a climbing group in the camp. He taught others how to walk on ice and studied secret maps. In 1942, he and his teammate Harrer tried to run away dressed as workers, but search dogs found them quickly. In 1943, they dug a tunnel, but it collapsed after 18m.

On April 29, 1944, seven prisoners cut the perimeter wire during a storm and split up. Only Aufschnaiter and Harrer headed north. They were carrying dry bread, a small gun, and a fake letter saying they were soil experts. After 65 days, they reached the Tibetan border.

Potala Palace, Lhasa. Photo: Wikimedia

Two years to Lhasa

The walk was 2,050km, with much of the route above 4,500m. According to Harrer’s book Seven Years in Tibet (1953), guards stopped them twice in Nepal. Finally, Aufschnaiter and Harrer went the long way around, adding weeks to their journey. Aufschnaiter lost two toes to frostbite, and Harrer lost 25kg. In December 1945, they climbed a mountain pass at 5,500m and saw Lhasa.

On Jan. 15, 1946, the two mountaineers walked into Lhasa. According to the 1993 American Alpine Journal, “the closer they came to the forbidden city, the less suspect they became.” Lhasa had 30,000 people at that time, and many temples. Aufschnaiter showed his fake papers to the government office, and the city needed workers, so he was soon signed up to work.

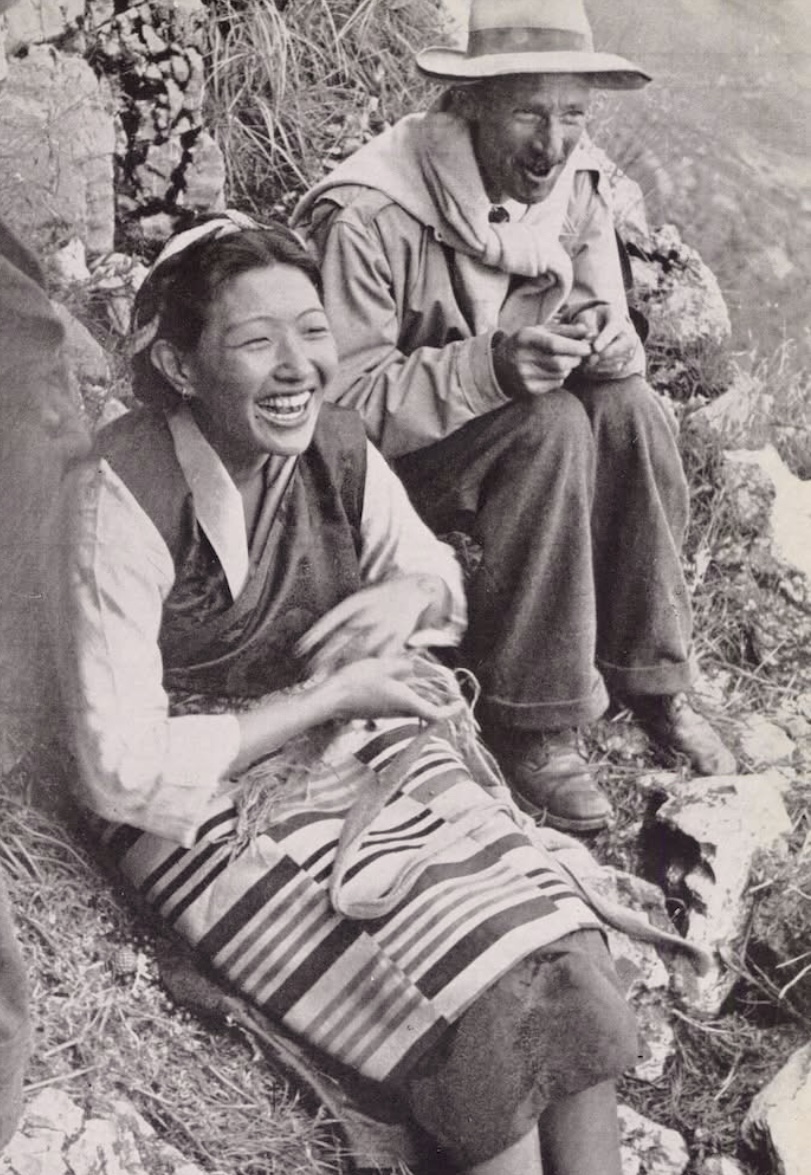

Peter Aufschnaiter with the Dalai Lama’s sister. Photo: Nepal Mountain Academy

Contributions in Lhasa

First, Aufschnaiter fixed the city water, as its old wooden pipes were losing half the water. He installed three kilometers of clay pipes and built a clean pond. After that, the situation in the city improved, as fewer people got sick.

Aufschnaiter didn’t return to Austria after fleeing the British internment camp but did use his position in Tibet to request high-yield potato tubers from European alpine regions via diplomatic mail and border traders in Kalimpong and Yatung. This helped people in Tibet grow 30 percent more food at 3,800m. He also drew maps of 200 hectares of grain fields and taught forty local men to measure land. He introduced vegetable gardening in the Lhasa valley, cultivating carrots and cabbage, and designing flood control dikes along the Kyichu River to protect farmlands.

By 1948, Aufschnaiter ran the land office in Lhasa. His map of Lhasa at a scale of 1:25,000 remained the best map until the 1980s. He also built a small power plant on the Kyichu River, providing the first electric lights to the Dalai Lama’s summer home. Aufschnaiter also surveyed seismic activity and installed a small hydroelectric turbine generating 20-30kW. While he worked, he filmed Tibetan daily life with a 16mm camera.

Meanwhile, Harrer taught the young Dalai Lama English and science. Harrer and Aufschnaiter met most nights to talk. Aufschnaiter’s notebooks (now in the Austrian National Library) are full of soil tests, ice measurements, and water-wheel drawings. These diaries, spanning 1944-1951, include over 1,000 pages of meticulous observations on geology, botany, and ethnography.

Peter Aufschnaiter with local dignitaries. Photo: Nepal Mountain Academy

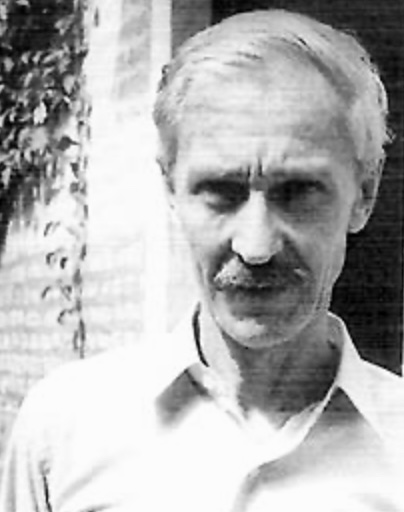

Losing his citizenship

After the war, Austria took away the passports of people who had stayed away too long. In 1950, Aufschnaiter received a letter stating that he was no longer an Austrian citizen. He eventually got his passport back in 1972, one year before he died, after persistent appeals.

In October 1950, Chinese guns sounded in the east, and Lhasa’s leaders discussed the possibility of fighting. The Dalai Lama asked Harrer for ideas, and Aufschnaiter drew safe roads to India, but continued working. When Chinese officers took Aufschnaiter’s office, they paid him to keep mapping, but said that he couldn’t leave the city. Finally, Aufschnaiter left secretly on his own with 40kg of papers on a mule.

Aufschnaiter worked in Gyantse and southern Tibet for approximately 10 months under Chinese supervision and then entered Nepal in 1951, taking a United Nations job in Kathmandu in 1952.

Peter Aufschnaiter. Photo: Archiv Senft

Climbing again at age 55

In 1955, Aufschnaiter joined a climbing team in India. On June 15, he and George Hampson reached the top of 6,069m Ronti.

“We went up the Nanda Kini valley, crossed Humkum Gala at 5,182m, and another pass by Nanda Ghunti. We camped on rocks near a snow gully with old slide marks. Starting at 6 am, we reached the top at 1:03 pm, and got back to camp at 5:15 pm,” they wrote in the American Alpine Journal.

The last 200m were steep ice, and Aufschnaiter cut steps with his old ice axe from 1939. After this outstanding alpine-style first ascent, Aufschnaiter explored routes on Tent Peak and other lesser mountains in the 1950s.

Books and movies

Aufschnaiter’s 1940 report on Nanga Parbat in the Zeitschrift des Deutschen Alpenvereins (Journal of the German Alpine Club) helps climbers today.

In Nepal, he wrote about Tibetan farms for the United Nations, and his book Peter Aufschnaiter: Sein Leben in Tibet (Eight Years in Tibet) was published ten years after his death, based on his manuscripts. It included detailed maps of Lhasa and the surrounding areas and surveyed its rivers and glaciers. The book also had agricultural notes on soil types, descriptions of irrigation systems, plus photos and sketches of Tibetan tools, houses, and water wheels. Aufschnaiter’s book was more like a government report, not an adventure story. An English translation followed in 2002, emphasizing scientific data over drama.

Peter Aufschnaiter’s grave in Kitzbühel, Austria. Photo: Wikimedia

Harrer published his book, Seven Years in Tibet, in 1953, and it sold millions of copies.

The 1997 movie, directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud, starred Brad Pitt as Harrer and David Thewlis as Aufschnaiter. The Hollywood adaptation was loosely based on Harrer’s 1953 memoir, sharing the core story of his WWII escape from the British POW camp, the Himalayan trek, and seven years in Tibet tutoring the 14th Dalai Lama amid China’s 1950 invasion.

A dramatic account

While the book presents a detailed travelogue showing Harrer’s complex character and his sometimes strained relationship with Aufschnaiter, the movie reduces Aufschnaiter to a minor role. It omits his contributions and personality, adds a fictional romance, downplays historical controversies, and prioritizes cinematic drama over accuracy. The movie is visually striking, but it is not a faithful version of their shared journey.

Aufschnaiter went home to Austria in 1960. He taught mapmaking in Innsbruck and took people trekking in summer. He passed away in Innsbruck on October 12, 1973, and was buried in Kitzbühel.