Today, Slovenian alpinist Nejc Zaplotnik would have turned 73. Widely regarded as one of the most influential climbers of his generation, he left an indelible mark on mountaineering through his bold ascents, philosophical writings, and tragic early death.

Zaplotnik’s resumé includes over 350 ascents across Europe, Africa, and North America. His career coincided with the golden age of Slovenian alpinism, characterized by ambitious expeditions to the Himalaya and other ranges, often with limited resources. We look at some of his notable climbs.

Jernej Zaplotnik, better known as Nejc Zaplotnik, was born in Kranj, Slovenia in 1952. He joined the town’s Alpine Association in 1969 and soon made a name for himself in the Slovenian and Yugoslav climbing scenes.

Alongside climbing partner Tone Percic, Zaplotnik climbed a difficult route on 2,558m Grintovec, the highest peak in Slovenia’s Kamnik-Savinja Alps.

In 1970, Zaplotnik joined the Mountain Rescue Service of the Slovenian Alpine Association. In 1971, he married Mojca Jamnik. Together, they had three children.

Grintovec Peak. Photo: JakobZ

Early climbs

Also in Slovenia’s Kamnik-Savinja Alps, Zaplotnik and Francek Ster made the first ascent of Tomazev Steber (Tomaz’s Pillar) on 2,540m Jezerska Kocna’s north face in 1971.

He also made several important climbs in Slovenia’s Julian Alps. On Triglav, Jalovec, and Skuta peaks, he climbed several routes, focusing primarily on winter and solo ascents. For example, in 1978, Zaplotnik ascended the difficult 900m Skalaska Route on the north wall of 2,472m Spik Mountain.

He finished another important solo climb in 1980, on the north face of 2,864m Triglav. Here, he ascended the extremely challenging Cop Pillar route.

His ski descents were also notable, including those on the north face of Kocna and Skuta. He made other ski descents on Triglav, Jalovec, and Grintovec peaks.

In 1976, Zaplotnik ascended the difficult Schmid Route of the Matterhorn with Ivan Kotnik. He and partner Marko Stremfelj then climbed the even harder Carlesso-Sandri Route on Civetta in the Italian Dolomites.

In 1972, Zaplotnik went to Tanzania to climb the east wall of 5,149m Mawenzi Peak in the Kilimanjaro massif. Next, he moved on to Yosemite and did the Salathe Wall with Janez Gradisar.

Mawenzi Peak. Photo: Altezza Travel

Makalu

Zaplotnik participated in three expeditions that completed new routes on three 8,000’ers: Makalu’s South Face, Gasherbrum I’s Southwest Ridge, and Everest’s West Ridge.

In the autumn of 1975, only one expedition targeted Makalu. Under the leadership of Ales Kunaver, the Yugoslav Himalayan Expedition chose to take on the unclimbed South Face. The 21-man team included Zaplotnik, Janko Azman, Stane Belak-Strauf, Janez Dovzan, Viki Groselj, Ivan Kotnik, and Marjan Manfreda, among others.

The South Face of Makalu. Photo: Summitpost

Other expeditions had tried Makalu’s South Face before. The Californian Makalu Expedition, led by William Siri, attempted the South Face–Southeast Ridge route in the spring of 1954, before the peak’s first ascent in 1955. However, the climbers aborted at 7,150m because of the approaching monsoon.

In the autumn of 1972, a Yugoslav expedition led by Ales Kunaver targeted the South Face without supplemental oxygen. In early November, climbers Miya Malezie and Janko Azman reached the top of the South Face at 8,100m. From there, they turned around, stymied by the route’s difficulty.

In 1974, two parties attempted the face again. An Austrian expedition led by Wolfgang Nairz reached 7,500m in the spring before aborting in bad weather. That autumn, Fritz Stammberger led an expedition that made it to 7,800m, but bad weather again foiled them.

Nejc Zaplotnik in Makalu Base Camp. Photo: Viki Groselj

The first ascent of Makalu’s South Face

Kunaver’s party arrived at Makalu Base Camp on Sept. 5, 1975. They established Camp 1 at 5,850m on September 7 and Camp 2 at 6,300m on September 9. On September 14, they bivouacked at 6,600m. They established Camp 3 at 7,000m on September 16 and Camp 5 at 7,500m on September 23.

Their rapid progress was interrupted soon after. Heavy snowfall and avalanches destroyed Camp 4. It took till October 2 to rebuild it. Camp 5 was established at 8,050m two days later. They later camped in snow caves to avoid avalanches.

The team summited in small groups. On October 6, Stane Belak-Staruf and Marjan Manfreda summited via the South Face. On October 8, Zaplotnik and Janko Azman reached the top, followed by Ivan Kotnik and Viki Groselj on October 10 and Dovzan on October 11. Manfreda didn’t use bottled oxygen, while the other summiters did.

The 1975 Slovenian route on the South Face of Makalu. Photo: Animal de Ruta

New route on Gasherbrum I

In the summer of 1977, Zaplotnik was part of a nine-man team that received a climbing permit for 8,080m Gasherbrum I in the Karakoram. Led by Janez Loncar, they would attempt the unclimbed Southwest Ridge.

The climbers navigated a complex icefall to set up Camp 1 at the base of a steep couloir. They progressed through challenging terrain — a rocky chimney, ice slopes, and a vertical rock pitch — to establish Camp 2 at 5,760m.

According to Zaplotnik’s report for the American Alpine Journal, from there, they climbed the White Dome’s avalanche-prone 50° slope. That day, an enormous slide narrowly missed them.

They set up Camp 3 at 6,340m, then descended to Base Camp to rest. Soon after, Loncar and Filip Bence fell ill, leaving only five fit climbers.

Andrej Stremfelj and Zaplotnik carried gear from Base Camp to Camp 2 in a day, and then moved it to Camp 3. Above Camp 3, Borut Bergant fixed some rope on the summit pyramid’s base. Then they climbed the steep, icy West Face on poor rock.

Andrej Stremfelj and Zaplotnik continued past the ropes alongside a 70° couloir that led to two snow shoulders. They placed Camp 4 on a precarious snow shelf somewhere between 7,000m-7,300m and endured a windy, sleepless night.

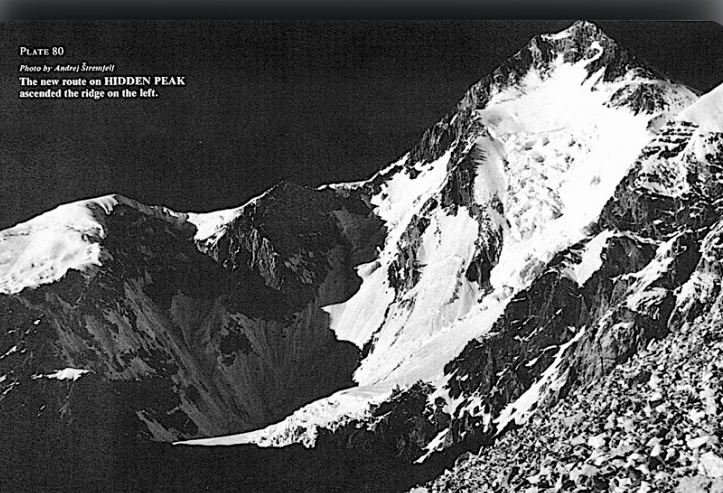

The new route on Gasherbrum I, along the ridge on the left. Photo: American Alpine Journal

The Southwest Ridge

On the morning of July 8, Stremfelj and Zaplotnik departed Camp 4. After hours of climbing on icy rocks, they reached a gap below the summit at midday. They finally summited Gasherbrum I in fog and extreme cold. At the summit, they raised the Yugoslav, Pakistani, and Slovenian flags, took a few useless photos in the fog, then began the difficult descent to Camp 4 in a blizzard.

Stremfelj and Zaplotnik missed the fixed ropes and had to navigate a vertical chimney to reach Camp 2 and then Camp 1.

Meanwhile, Drago Bregar was at Camp 4, intending to push for the summit. But on July 10, the team lost contact with him. Some team members tried to reach the upper slopes to look for him, but on July 14, it started to snow again. They couldn’t find Bregar.

“I sat at Base Camp, looking at my second 8,000’er, Bregar’s grave,” Zaplotnik wrote.

Andrej Stremfelj, Nejc Zaplotnik, and Marko Stremfelj before their summit bid on the Everest West Ridge Direct in 1979. Photo: Andrej Stremfelj

New route on Everest

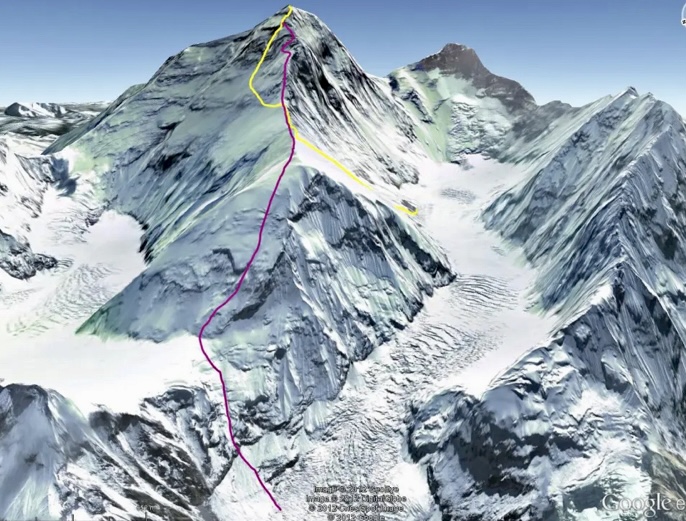

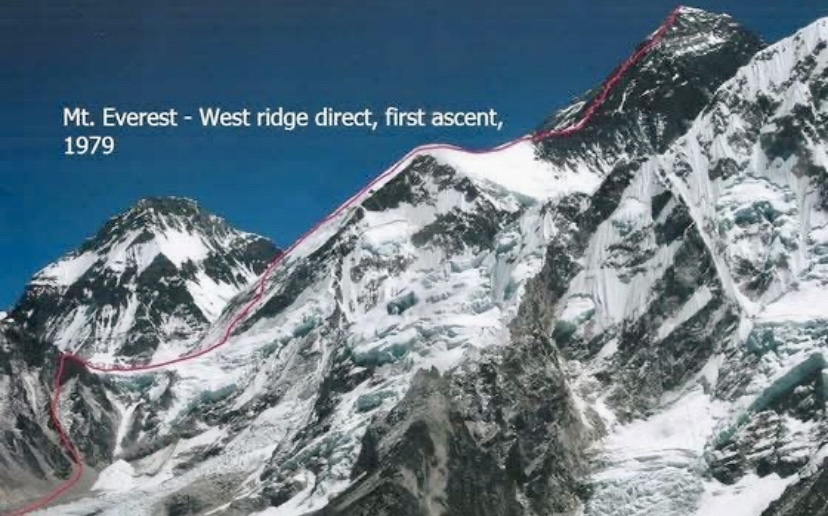

In the spring of 1979, a strong Slovenian team led by Tone Skarja and including Zaplotnik tried a new route on Everest — the complete West Ridge, also known as the West Ridge Direct.

The expedition arrived at Base Camp at the end of March with 700 porters. The climbers scouted the safer Lho La route, transported loads to the pass, and tested gear. For the next month, they established camps to 7,300m, fixing ropes on very steep terrain.

Storms delayed progress until May 9, when they established Camp 5 at 8,120m. On May 10, Viki Groselj and Marjan Manfreda attempted the summit but retreated at 8,300m because of route-finding issues, oxygen valve failures, and frostbite.

On May 12, Dusan Podbevsek and Roman Robas faced similar navigation challenges, barely surpassing 8,300m.

The Everest West Ridge Route of 1979. Photo: Animal de Ruta

The West Ridge Direct

On May 13, brothers Andrej and Marko Stremfelj and Nejc Zaplotnik left Camp 5 in brutal -35° cold plus a wind. Marko turned back because of a faulty oxygen valve, but Andrej Stremfelj and Zaplotnik pressed on. After climbing a very demanding short section on the upper part of the peak, the two climbers rejoined the American Route and the Hornbein Couloir, summiting in the early afternoon.

On May 15, Stane Belak, Stipe Bozic (filming the ascent), and Ang Phu Sherpa left Camp 5 after a snowfall delay. As a trio, they moved slower, reaching Everest’s summit at 2:30 pm. During their descent, they were forced to bivouac in the open at over 8,200m on the Hornbein Couloir.

Borut Bergant, Ivan Kotnik, and Vanja Matijevec had been waiting at Camp 5. They found the trio below the couloir, seemingly fit to descend. Tragically, Ang Phu then slipped and fell 1,800m to his death. They discovered the body the next day.

Because of the accident and oxygen system failures, they made no further attempts.

The 1979 route. Photo: Stipe Bozic

The difference between the 1963 and 1979 routes

The 1979 Everest West Ridge Direct and the 1963 American Route (by Willi Unsoeld and Tom Hornbein) both tackled Everest’s West Ridge, but their routes and approaches differed.

The 1979 team climbed the entire West Ridge from Lho La (6,050m) to the summit, a 6.5km route. This was the first confirmed full ascent of the West Ridge, avoiding deviations. The team of 24 climbers, with five summiting (A. Stremfelj, Zaplotnik, Ang Phu Sherpa, Belak, and Bozic), faced UIAA Grade V challenges near the summit. They used supplemental oxygen above Camp 5 (8,120m) and fixed ropes extensively.

Unsoeld and Hornbein climbed from the Western Cwm in 1963, joining the West Ridge at around 7,500m. They then diverged to the Hornbein Couloir (8,000-8,500m) to the summit. This partial West Ridge climb, covering less of the ridge’s full length, was the first traverse of Everest. The pair descended via the South Col, using minimal fixed ropes and limited oxygen.

Nejc Zaplotnik on the summit of Everest. Photo: Andrej Stremfelj

Lhotse South Face attempt

In the spring of 1981, Zaplotnik was a member of the Lhotse South Face Expedition led by Ales Kunaver. The team progressed well but abandoned their attempt on May 20 at 8,250m because of bad weather and exhaustion.

Zaplotnik’s death

In the spring of 1983, the Split Alpine Expedition set off for 8,163m Manaslu. Led by Vinko Maroevic, they targeted the dangerous South Face–South Ridge route. The team had 16 climbers, including Zaplotnik, and decided not to use supplemental oxygen.

The expedition started well, and they established four high camps, reaching 7,101m.

However, on April 24, an avalanche hit some of the climbers roughly 100m above Camp 1 on the Manaslu Glacier. It killed Zaplotnic and Ante Bucan. Srecko Grekov was badly injured.

Zaplotnik was 31 years old, which seems young considering how much he had already accomplished.

For more details on Zaplotnik’s life and career, we highly recommend Zaplotnik’s book Pot. It’s a cult text, a ”bible for a generation,” as Slovenian climber Marko Prezelj once said.

We also recommend Bernadette Mcdonald’s book Alpine Warriors and her excellent article Nejc Zaplotnik Mountain Poet, published in Alpinist.