Again this year, the first death of the season is that of a local high-altitude worker. Once again, the cause of death was not a mountaineering accident, such as a fall or an avalanche. The key question, however, is not how Lakpa Tenji Sherpa died, but why.

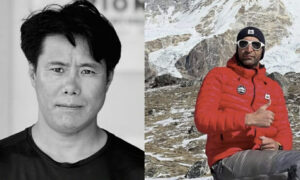

Lakpa Tenji Sherpa worked with Seven Summit Treks. He summited Makalu on May 6.

“He passed away at Camp 3 while his fellow guides were carrying him down,” Rakhesh Gurung, the head of Nepal’s Department of Tourism (DoT), told Everest Chronicle.

Didn’t feel well

According to the paper, the agency told the DoT that Lakpa Tenji, 54, “didn’t feel well during the descent.” Publicly, Seven Summit Treks only reported that their group of 11 reached the summit at 3 pm — four foreign clients and seven Nepalese workers.

Later, they added Flor Cuenca of Peru to the list. She climbed without oxygen or sherpa support beyond Base Camp. Cuenca typically keeps her climbs quiet until she finishes.

The only climber in that group who shared her live tracker was Allie Pepper of Australia, who also climbed without oxygen. Pepper reached Camp 3 at almost midnight Nepal time, according to her tracker.

The team reached Advanced Base Camp the following day (yesterday). Currently, she is on the way to Makalu’s lower base camp. It is unclear what other members of the team did.

Conditions on Makalu have been tough in the last few days. The lack of snow on the route forced climbers to deal with rock, ice, and relentlessly high winds.

After the summit and throughout yesterday, Seven Summit Treks shared several congratulatory posts on social media, praising the achievement of their clients. Some members (or their home teams) have also announced their summits. But not a word of what had happened that day, how Lakpa Tenji was dragged by other sherpas, and how he died at Camp 3.

“None of the Seven Summit Treks representatives were immediately available to discuss the circumstances of the death,” wrote Everest Chronicle.

Impossible without sherpas

And yet, on commercial expeditions, sherpas are vital to everyone’s safety and success.

“I just had breakfast with other Makalu climbers from Imagine Nepal and couldn’t stop talking about how amazing our sherpas were,” Naila Kiani told ExplorersWeb from Kathmandu, where she flew after summiting Makalu on May 5.

“Conditions were so tough, we couldn’t have summited without them.”

For Kiani, Makalu was her 11th 8,000’er and the second toughest mountain of her life, after an epic on Gasherbrum I. There, only a handful of people proceeded without ropes through heavy snow on the upper sections, and she had to support her sick partners.

On Makalu, the route between Camp 1 and Camp 2 was particularly hard because of strong, cold winds.

“I’ve never experienced such cold temperatures,” Kiani said. “And the terrain was all rock, blue ice, and ice swept by the wind.”

She explained how the sherpas give not only physical and logistical support but also motivate them.

“They work so hard and yet they are always singing and smiling. On the way to Camp 2, I wanted to turn around, but Phur Geljen encouraged me to reach the camp and rest there. ‘Then you decide,’ he said. That guy is amazing.”

Workers under pressure

Her guide never pressured her either to continue or to turn around. “He repeated that I could decide what to do at any moment.”

However, in this time of industrialized climbing and nearly guaranteed summits, this is not always the case. Contrary to what happens with guides in Europe or America, sherpas have no authority to turn a client around. This is true even when it is obvious that the person is in no state to proceed but insists on continuing.

On the other hand, a high-altitude sherpa earns more on an expedition than he would in a normal job for an entire year. He can also expect a bonus and tips if they reach the summit. Finally, there might be pressure from expedition leaders, who actually have the last word. This is a toxic mix that can easily lead to tragedy or near tragedy, as happened last year with Indian climbers Baljeet Baur on Annapurna and Piyali Basak on Makalu.

Thus, the key question we asked at the beginning of this article: Why did Lakpa Tenji die? Was he healthy and fit enough? Was he under pressure to continue, either from the climber, the expedition leader, or himself?

We just don’t know. But something has to change in the relationships between high-altitude guides, their clients, and the expedition leaders.

Hard conditions on May 6

Meanwhile, climbers continue to go up and down Makalu. Kiani confirmed that she met Allie Pepper and Flor Cuenca on her way down between Camp 2 and Camp 3 on May 5.

They were both going strong, especially Cuenca, “the strongest woman on the mountain,” said Kiani. The Pakistani climber recorded the moment they met, below.

As always, Cuenca carried her gear and tent, used no oxygen, and was not supported. We will ask Cuenca about what happened when she returns to town.

Kiani also noted that the winds decreased temporarily on May 5, but then increased again. So the summit push on May 6, which included the Seven Summit Treks group, may have been very tough.

Bartek Ziemski and Oswald Pereira of Poland also launched a no-O2 summit push on May 5 at 8 pm, hoping to summit the same day as the 7ST team. However, the cold and Ziemski’s worsening respiratory problems forced them back at 7,950m around 2 am.

They retreated to Camp 3, left some gear there, and continued to Base Camp. Ziemski still hopes to have another chance to ski down from the summit. Snow is currently falling and may improve skiing conditions.

Another Pole, Marcin Miotk, is currently on his way up, aiming to summit on May 11. Nirmal Purja also summited Makalu with his Elite Exped group, but he didn’t specify a summit date. Finally, an 8K Expeditions client, Liliya Ianovskaia of Canada, summited today, supported by brothers Migma Dorchi Sherpa and Dawa Tasi Sherpa.