In 1978, American mountaineer Johnny Waterman completed the first solo ascent and traverse of Mount Hunter’s twin summits in Alaska. His grueling 145-day odyssey redefined the limits of solo mountaineering, showcasing incredible endurance and skill. We examine the climb, its significance, and Waterman’s legacy.

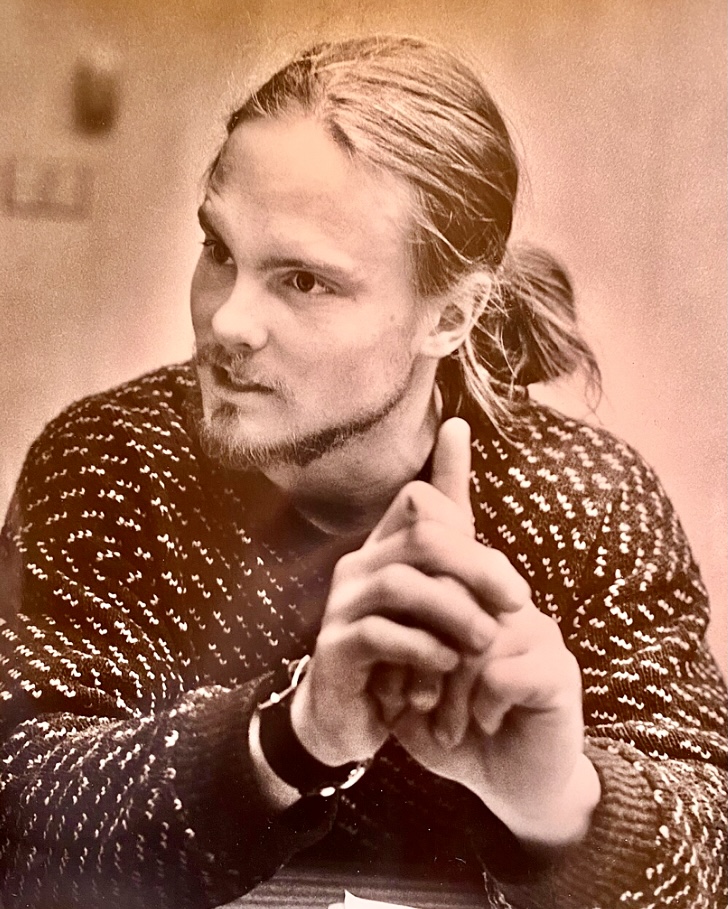

Johnny Waterman. Photo: Laura Waterman

Johnny Waterman

John Mallon Waterman, better known as Johnny Waterman, was born in 1952. He grew up climbing with his father, Guy Waterman (a mountaineer and conservationist who also wrote several books about the outdoors), and his older brother Bill.

When Johnny Waterman was still in his teens, he began backpacking and rock climbing in New York and New England. He led a 5.10 route (Retribution) in the Shawangunk Mountains in New York State at 15. At 16, he climbed McKinley’s West Buttress with the Appalachian Mountain Club.

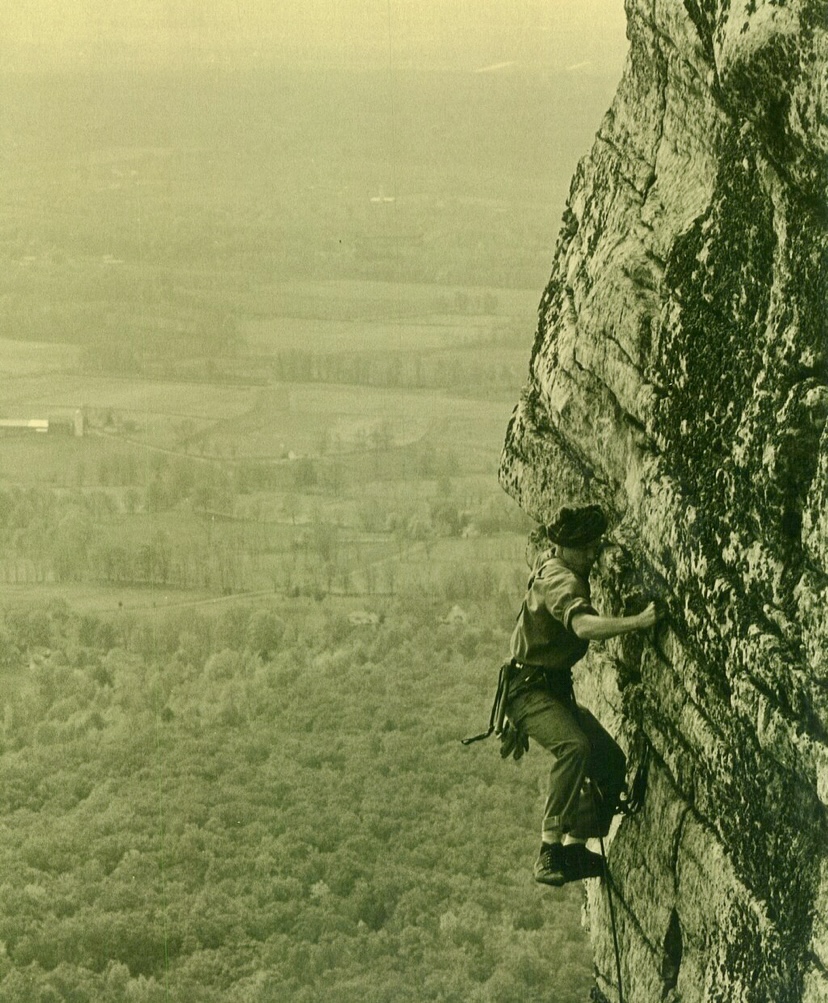

Johnny Waterman’s father, Guy Waterman, on a cliff. Photo: Wikimedia

According to Bradley Snyder for the American Alpine Journal, Waterman was years ahead of mainstream mountaineering: “John might have coasted through mountains on sheer natural ability, but he took the craft of climbing seriously, and trained himself to be a fast, safe, consistent climber on any terrain.”

Notable climbs

After high school, Waterman made trips to England, Scotland, Canada, the Alps, and Turkey, and carried out several remarkable ascents. In Canada, he made the second ascent of Snowpatch Spire’s South Face.

The South Face of Snowpatch Spire. Photo: SummitPost

Waterman made the first solo ascent of the committing VMC Direct route on 1,244m Cannon Mountain in New Hampshire, a mind-blowing feat.

He ascended The Nose of El Capitan, soloed the Grand Teton’s North Face, and carried out the first south-to-north traverse of the Howser Towers.

He made the first ascent of Mount McDonald’s North Face and the first ascent of the East Ridge of Mount Huntington. On Mount Robson, he made the third ascent of the North Face.

Mount Hunter. Photo: Ross Fowler

Mount Hunter

Mount Hunter (also called Begguya) is 13km south of Mount McKinley, in the Alaska Range within Denali National Park.

Begguya means child, or Denali’s child, in the local Dena’ina Athabascan language. It is famous for its technical difficulty, steep faces, and remoteness. Elite alpinists are drawn to its challenging routes, extreme weather, and beauty.

Mount Hunter has two summits: the North Summit at 4,442m and the South Summit at 4,255m. A high plateau connects the two summits, making the traverse an unusual challenge. Its climbing history features several bold ascents, technical innovation, and few summits, especially compared with McKinley.

Fred Beckey, Heinrich Harrer, and Henry Meybohm made the first ascent of Mount Hunter in 1954 via the west ridge from the Kahiltna Glacier. They topped out on the North Summit on July 3. Their multi-day route passed over crevassed glaciers, steep snow slopes, and a corniced ridge.

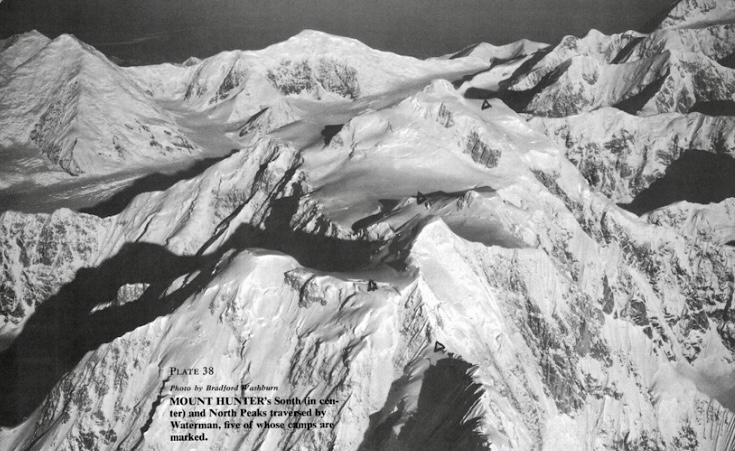

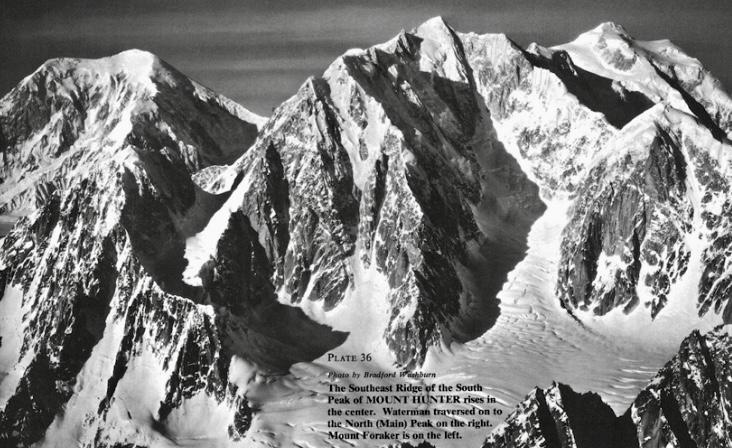

Mount Hunter’s South (center) and North Summits. Photo: Bradford Washburn

A bold attempt on Mount Hunter in 1973

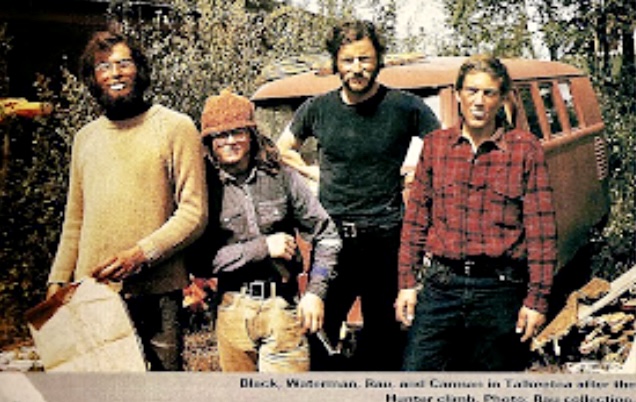

In May 1973, Waterman and partners Dean Rau, Don Black, and Dave Carman attempted the first ascent of the south face-south ridge route of Mount Hunter. Waterman, then 21 years old, aimed for the 4,257m South Summit.

On May 29, Black, Waterman, and Carman were 61m below the South Summit when they mistakenly halted at a gendarme because of an approaching storm and confusion with the North Summit. (Rau had stopped lower down.)

Their route from the south col (3,200m) comprised three demanding sections: a complex lower rock ridge requiring 914m of rope and 40 anchors; a steep middle mixed face with ice-filled cracks; and an upper snow-ice ridge with unstable ice and minimal belays.

A storm trapped the climbers in a snow cave for days, with high winds and almost zero visibility. The climbers were running out of food, and Waterman had frostbite. The exhausted trio retreated from below the South Summit. Despite the failure, Waterman decided to return one day to solo Mount Hunter.

Left to right, Don Black, Johnny Waterman, Dean Rau, and Dave Carman after the 1973 Mount Hunter attempt. Photo: Dean Rau Collection

After 1973, Waterman moved to Fairbanks, Alaska. He preferred solo climbing because he struggled to find equally skilled partners, and possibly because of a tragic event in 1973. Johnny’s beloved brother, Bill, who had lost his leg in a railroad accident in 1969, disappeared in Alaska in 1973. Bill was only 22 years old.

After this, Waterman became more isolated and increasingly climbed solo.

Mount Hunter. Photo: Brian Okonek

Mount Hunter solo traverse, 1978

Waterman returned to Mount Hunter alone in the spring of 1978.

“My vendetta with Mount Hunter started in the late 1960s, with Bradford Washburn’s pictures in the American Alpine Journal,” Waterman wrote in his climbing report for the AAJ.

Driven by a decade-long obsession, Waterman began a solo south-to-north traverse. Starting on March 24 from the Tokositna Glacier’s cirque at 2,438m, he aimed to climb the 1,433m Central Buttress of the south face (referred to as the southeast spur in mountaineering literature), then traverse the summit plateau and descend the north spur.

He had 1,097m of rope and more than 350kg of gear, including food calculated to provide 5,000 calories a day.

The southeast spur with the South Summit in the center. Waterman traversed onto the North Summit on the right. Mount Foraker is on the left. Photo: Bradford Washburn

The climb

Waterman adopted an expedition-style approach, shuttling his 272kg base camp up each section, reusing rope to cover a route requiring 3,658m. The ascent involved 12 camps and 12 round trips per section.

The Central Buttress was mostly snow and ice, with rock steps and a 107m rock cliff. Section one included a 366m gully, and section two tackled a 152m technical crux, including a 24m pinnacle and a 90m gully. On April 11, day 18, he reached Camp 3.

Next came a 488m corniced arete, featuring a 30m headwall and ice pinnacle, which he finished on May 6. The next section wasn’t easy, either. He climbed steep terrain, joining the south ridge at 3,871m on May 26.

During the climb, Waterman suffered frostbite, lost a contact lens, and had a lice infestation. He dealt with fraying ropes, cornice collapses, and food shortages, dropping to two-thirds rations by June. A resupply on June 20 (day 88) provided 36 days of food.

By June 12, he reached the summit plateau after navigating a 213m ice arete. He topped out on the South Summit on July 2 after 101 days. After traversing the two summits, he reached the North Summit on July 26.

He descended by the north spur, arriving at his fly-out site 43 days later. His solo expedition took an astonishing 145 days. According to his report, Waterman used 40 ice pitons, pickets, and flukes, and 20 rock anchors.

His new route was the first solo ascent and the first solo traverse of the peak. He endured loneliness, rage, and frustration, but persevered, managing limited food supplies to complete his climb.

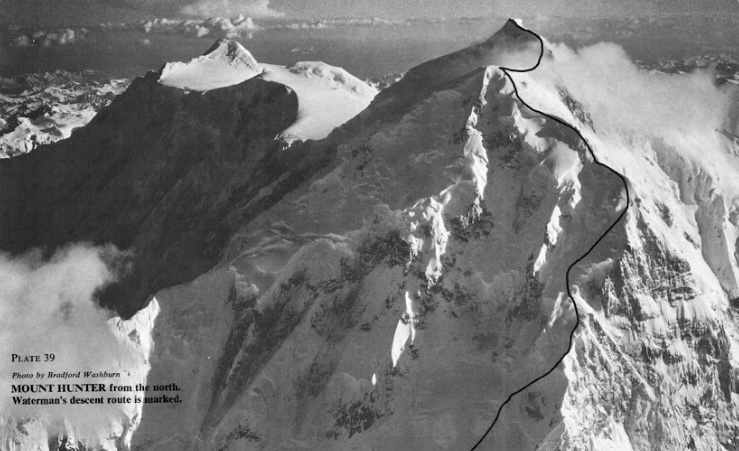

Mount Hunter from the north. Waterman’s descent route is marked. Photo: Bradford Washburn for the American Alpine Journal

After the climb, Waterman’s mental health deteriorated. He displayed obsessive and delusional behavior. His past climbing feats convinced him he was invincible.

Disappearance

In the spring of 1981, Waterman targeted McKinley solo via the East Buttress. He planned to climb up the northwest fork of the Ruth Glacier, a route prone to crevasses and avalanches. Waterman began on April 1, carrying minimal supplies. He was last seen on April 19 at 3,350m.

Helicopters and ground rescue teams found only some tracks and an abandoned campsite. He might have suffered a fatal crevasse fall, died in an avalanche, or, with minimal gear, perished of exposure. Waterman was 29 years old when he disappeared.

Aftermath

Waterman’s father, Guy Waterman, committed suicide in February 2000, intentionally freezing to death on Mount Lafayette in New Hampshire. Laura Waterman, Guy Waterman’s wife (and Johnny Waterman’s stepmother), created The Waterman Fund after his death. The fund promotes wilderness preservation through education, trail maintenance, and research. The present an annual Guy Waterman Alpine Steward Award, honoring those dedicated to protecting the region’s mountain wilderness.

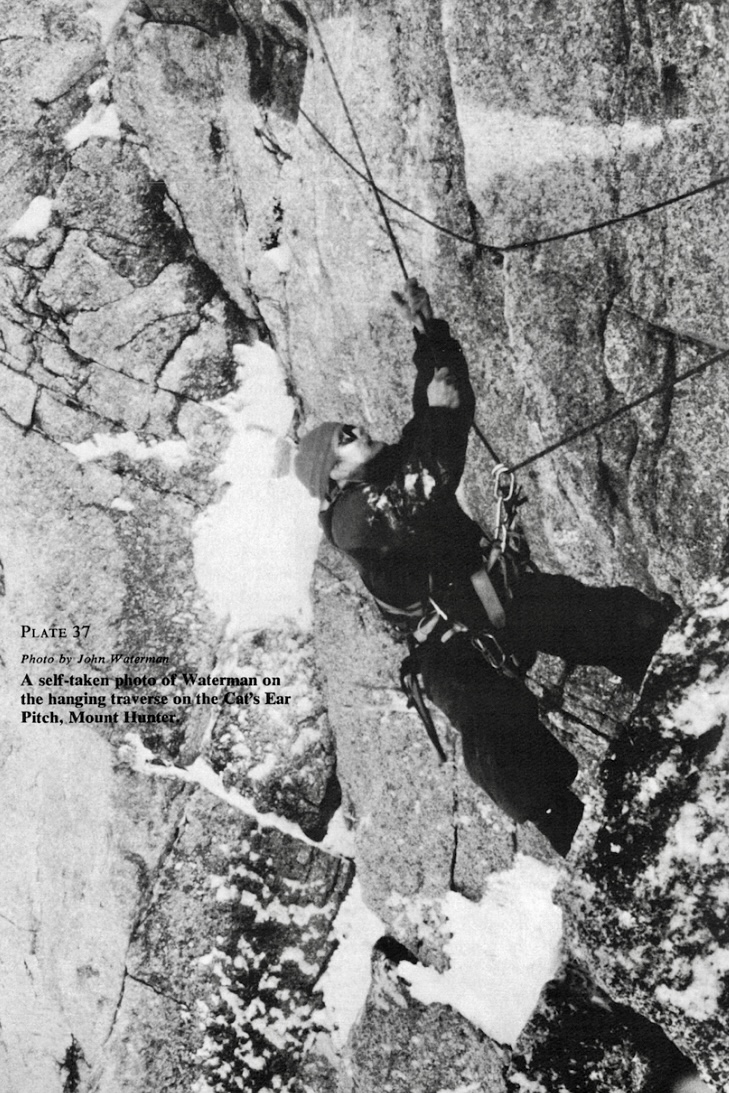

Johnny Waterman on Mount Hunter. Photo: Johnny Waterman