Exploration has always attracted a certain amount of fraud. Ancient mariners claim to have sailed to the North Pole. Both arctic explorers and conquistadors sold their royal patrons the promise of gold in remote lands in other to fund their next expeditions.

But forgeries are different. The motivation behind these deliberate quasi-historic creations is harder to figure out. Sometimes it may simply come from a perverse desire to put one over on self-serious researchers. Other motives are more commercial. Here, we consider six famous deceptions and try to get into the minds of the forgers themselves.

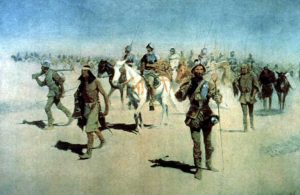

A group of scholars examines the Piltdown Man. Painting: John Cooke

Piltdown Man

In 1912, amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson made a bold claim. An advocate of human evolutionary theory, he professed that he had found the “missing link” between man and ape in Piltdown, Sussex. He presented a humanoid skull with an ape-like jaw, along with bone and skull fragments and primitive tools to a geologist named Arthur Smith Woodward at the British Museum. Smith Woodward believed every word and invested greatly in the find’s authenticity.

Scholars declared that the skull was over 500,000 years old and called it Eoanthropus Dawson. In 1915, a team led by Dawson found a second skull with similar attributes close to the original site. For a few decades, it stood as the main piece of evidence of humanity’s evolution from apes.

The hoax held up until 1953 when modern scrutiny proved that it was a composite of a medieval human skull, a 500-year-old orangutan jaw, and chimpanzee teeth. Examination under a microscope found file marks on the teeth. Subsequent investigations in 2009 and 2016 found the canines and molars had been filed down methodically and artificially stained. They also contained silicate putty.

Dawson died in 1916 without ever confessing. But all fingers point to him as the culprit. An archaeologist named Miles Russell discovered that Dawson had 38 forgeries in his collection, ranging from primitive tools to fossilized toads. It was no secret that Dawson had tried for many years to join the Royal Society. Most likely, Dawson yearned for fame and prestige among the great minds of his time.

An 1869 photo of the Cardiff Giant. Photo: New York State Historical Association Library

Cardiff Giant

In 1868, an atheist named George Hull wanted to prove a point. After getting into a heated debate about religion and the belief that giants once roamed the Earth, as cited in the Book of Genesis, Hull began an expensive and elaborate mission to prove the gullibility of Christians.

He had a 3.2m high block of gypsum quarried and sculpted by stonemasons, whom he swore to secrecy. They made a giant man based on Hull’s own appearance. The completed giant weighed over 1,350kg and measured three metres tall. Hull put on finishing touches like acidic stains and pores on the skin. This whole project cost him $2,600 at the time — about $54,000 today. Hull planned to present it as an example of human petrification, a popular notion at the time.

He wanted to bring it to Mexico but this proved too difficult so he buried it on his cousin’s farm in Cardiff, New York. He waited a year, then hired workmen to dig a well on the property. After a few metres, they were shocked by the giant’s appearance. This ‘discovery’ took place in 1869.

Soon, hundreds of people swarmed to see the giant. Hull, his cousin, and many businesses in the area profited from the stunt. However, not long after, real paleontologists examined the giant and declared it an obvious fake.

Hull sold the giant to a group of wealthy men for $23,000 — almost half a million of today’s dollars. So despite his large initial investment, he made an unexpected killing. Impresario P.T Barnum offered to buy it, but the consortium refused, so Barnum created one of his own, which he declared was the original.

“There’s a sucker born every minute,” one man reportedly said about those who paid to see this fake giant. Somehow, the quote came to be attributed to Barnum himself.

The Cardiff giant was called the Great American Hoax, but Hull had achieved his goal. The Methodist community with whom he had argued about evolution, geology, and alchemy fully believed to the very end that the giant was real.

Galileo Manuscript

For many years, the University of Michigan boasted about its possession of an original manuscript written by Galileo himself, dating to 1609. The manuscript contains diagrams and notes on Jupiter’s moons. The university acquired it in 1934 and its fame continued until just last month, August 2022.

Galileo manuscript notes and diagrams. Photo: University of Michigan

The library received a call from historian Nick Wilding. His reputation for exposing forged historical material struck fear in the hearts of collectors and academics alike. He had exposed several Galileo manuscript fakes in the past. Wilding caught the manuscript out because of oddities in its ink, wording, and handwriting. The final blow was the paper’s watermark “BMO”, which revealed that it had been made in Bergamo, Italy. This watermark did not show up on documents until 1770.

The culprit behind the deception turned out to be Italian forger Tobia Nicotra. In the 1930s, he forged over 600 documents, particularly autographs of famous figures like Abraham Lincoln, Mozart, and Christopher Columbus. He would take blank pages from old and rare books to make his autographs, thereby destroying them. He eventually got caught in 1934.

Vinland Map

Three years before the 1960 discovery of the Viking site at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Yale University acquired a peculiar mappa mundi, or medieval European map, that dated to the 15th century. It included most of the continents, as well as a place called Vinland. This suggested that Vikings had explored the New World before the Age of Discovery.

The Vinland Map. Photo: Yale University Press

Several scientists raised doubts, which led to the Vinland Map Conference of 1966. An investigation found discrepancies in the text, ink, and odd substances on the parchment. The ink contained titanium, which only came into use around the 1920s. The text also had Latinized words only seen in the 17th century. The biggest shock of all was the presence of nuclear fallout — likely from those 1960s tests — on the parchment.

The forger concealed a bookbinder’s inscription on the back of the map, which might have given away the hoax, by writing over it with modern ink — clearly, a failed strategy. The identity of the forger remains unknown.

Pompey Stone

In the summer of 1820 in Pompey, New York, a farmer name Philo Cleveland came across an oval stone with odd inscriptions on it. The stone measured 36cm long, 30m wide and 25cm thick. It weighed around 58kg. The inscription read Leo De L on VI 1589, along with an illustration of a snake wrapped around a tree.

Pompey Stone. Photo: Eddie891/CC BY-SA 4.0

Historians were confused about its meaning and origin. Some thought it the headstone of a Spanish settler. Others suggested that it was connected to Ponce De Leon’s search for the fountain of youth. Still others thought that a Jesuit priest had carved it. Many dug into its cryptic message, not realizing it was completely fabricated out of apparent boredom.

In 1894, a clever antiquarian discredited the stone based on careful examination and analysis. Later that year, an engineer named John Edison Sweet admitted that his uncle had carved the stone as a joke, just to see what would happen if anyone found it.

Like many famous fakes, the stone eventually ended up in a small regional museum, in this case, the Museum of the Pompey Historical Society.

Etruscan Terracotta Warriors

Two brothers, Pio and Alfonso Riccardi, and their sons basically turned forgery into a family business. They created three iconic Etruscan statues, sourcing information from ancient texts and help from other sculptors between 1915 to 1918. They sold the three statues, the Old Warrior, Big Warrior, and Colossal Head to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York shortly after. Each work is about two metres tall.

All went well until some details acquired unwanted attention from critics. They found the statues too well-preserved and too brightly colored to be thousands of years old. It also contained details not common in Etruscan art.

A sculptor named Alfredo Fioravanti, who helped the brothers, confessed to the scheme in the early 1960s.

Etruscan terracotta statue, the so-called ‘Big Warrior’. Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art