In the spring of 1933, a young English mathematician of extraordinary promise, Raymond Paley, arrived in Skoki Valley in the Canadian Rockies for a brief skiing holiday. Unfortunately, it became his final journey. Today, we revisit his story.

Raymond Paley was born on January 7, 1907, in Bournemouth, England. His father was an artillery officer who died of tuberculosis several months before Raymond’s birth. His mother, Sybil Maude Scott, later remarried, and the boy (known as “Kit” to family and friends) grew up largely with his maternal grandparents in Weymouth.

Raymond Paley’s brilliance was obvious from the start. He won a scholarship to Eton College, where he combined his schoolwork with success in athletics, including hammer throwing. In 1926, he went to Trinity College, Cambridge, to study math under the guidance of influential British mathematicians Godfrey Harold Hardy and John Edensor Littlewood.

Paley graduated with distinction and collected several college prizes, including the 1930 Smith’s Prize, one of the highest distinctions open to young Cambridge mathematicians. He immediately became a Research Fellow at Trinity.

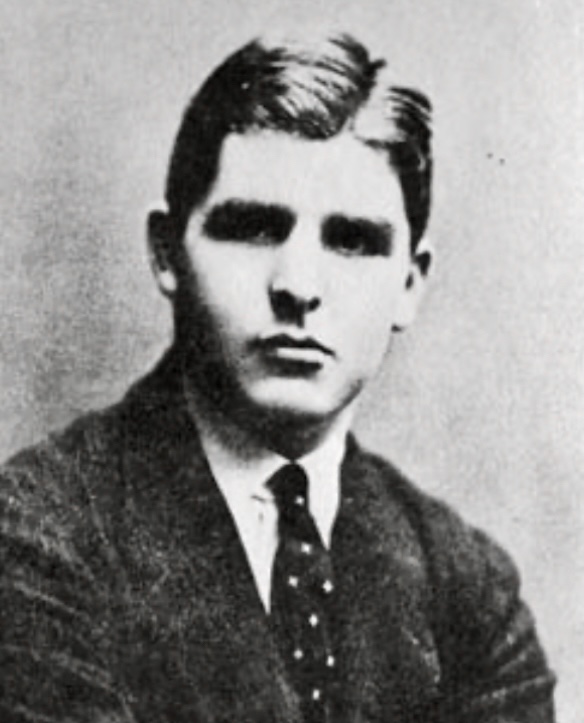

Raymond Paley. Photo: mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk

Contributions in math

Even among the exceptionally talented generation at Cambridge in the late 1920s, Paley stood out. Hardy described Paley as brilliant, and contemporaries praised his exceptional technical power and originality.

In a career of barely five years, Paley published 26 papers, almost all in major journals. He worked first with Littlewood to create what is now called the Littlewood–Paley theory. Then in 1930–1931, he spent a year in Warsaw with Antoni Zygmund, a world-renowned Polish-American mathematician regarded as one of the 20th century’s leading figures in harmonic analysis.

In the autumn of 1932, Paley crossed the Atlantic on a Rockefeller International Research Fellowship and joined Norbert Wiener, a brilliant American mathematician and philosopher, and recognized as the father of cybernetics, at MIT. In short, Paley was a generational talent.

Skoki Lodge. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Skoki Lodge

In early April 1933, while still at MIT, Paley decided to take a short break and travel north for skiing. He chose the Skoki Lodge in Banff National Park, Alberta, one of the first backcountry ski lodges in North America and the first in Canada.

The lodge’s story began in the autumn of 1930, when local Banff ski pioneers Clifford Whyte and Cyril Paris, with help from outfitter and builder Earl Spencer, built the original single-storey log cabin. It was modest in size, approximately 37 square meters, and located in the remote Skoki Valley, a classic Rocky Mountain backcountry basin.

The first ski parties arrived there in the winter of 1931 under the auspices of the Ski Club of the Canadian Rockies.

By 1932, some additions had appeared: a kitchen extension to the main building, two small guest cabins, and a halfway hut for resting on the 14.5km approach trail from near Lake Louise.

Management in these early years passed to Clifford Whyte’s younger brother, Peter, and his wife, the artist Catharine Robb Whyte. They were both passionate skiers, painters, and local figures who helped shape the lodge into a welcoming haven for adventurous winter travelers.

Still rustic

Even by spring 1933, just two to three years after the construction began, Skoki remained profoundly rustic and isolated. There was no electricity (there still isn’t), no road access (still none), and no running water or indoor plumbing. Guests had to ski or hike to get there. It was a true pioneer outpost in the wilderness.

(An interesting fact: In July 2011, Prince William and Princess Catherine of Wales — then the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge — enjoyed a private 24-hour retreat at Skoki Lodge, where a temporary, helicopter-delivered flush toilet was specially installed for their visit. The former Canadian Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, also vacationed here with his family.)

A view back toward Lake Louise from Deception Pass. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

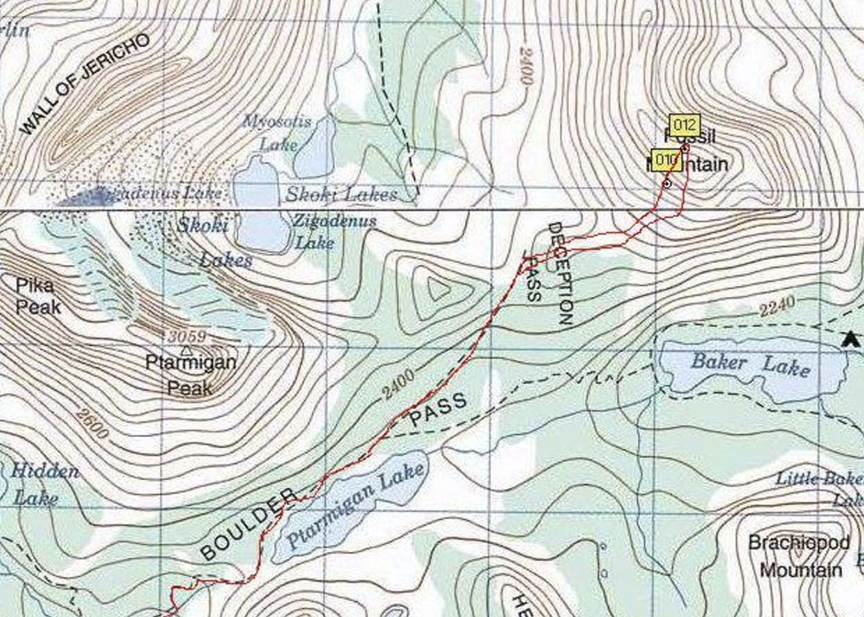

Fossil Mountain and Deception Pass

Fossil Mountain (2,946m ) lies a short distance south of 2,707m Skoki Mountain. Morrison Parsons Bridgland (a prominent surveyor and pioneering alpinist who mapped the Canadian Rockies between 1902 and 1930) named the mountain in 1906 after finding abundant Devonian fossils embedded in the limestone. Fossil Mountain consists largely of long scree slopes and broken rock. In summer, it is a moderate scramble, but in early spring, the upper slopes may be prone to avalanches.

Deception Pass, about 2,340m, lies between Fossil Mountain and 3,059m Ptarmigan Peak. The name is well-earned, at least from the Skoki side: You surmount a series of humps that each look like the top of the pass. But for quite a while, there’s always a new hump beyond. From the Lake Louise side, it’s not deceptive at all, just a straightforward slope up from windy little Ptarmigan Lake.

Fossil Mountain, lower left. Photo: Jockurutherford/Wikimedia

The accident

The Whytes and other experienced guests warned Paley that the spring snowpack in the high country could be unstable due to old layers beneath fresh windslab, and that skiing alone in exposed terrain was dangerous. Despite the warnings, on the morning of April 7, 1933, Paley left the lodge alone on skis, heading up toward Fossil Mountain.

He climbed steadily, reaching about 2,900m near Deception Pass. There, while traversing a steep ledge loaded with wind-packed snow overlying loose rock, his weight triggered a large slab avalanche. The snow broke away suddenly in a heavy, dense mass, sweeping Paley down the slope in seconds. Several other skiers, positioned lower on the mountain, out of the slide path, saw Paley carried away by the debris. They hurried back to the lodge to raise the alarm.

In the afternoon, park wardens from Banff National Park, assisted by a member of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, reached the avalanche debris field. The recovery work was slow and exhausting, but after several hours of digging, they finally located Paley’s body and brought it down to Banff. He was buried in the Old Banff Cemetery.

Paley’s death in 1933 was only the third registered backcountry ski death in Canada. Most previous avalanche fatalities had been construction workers, although the first known avalanche deaths in Canada occurred far back in 1782, when 22 Inuit died in a slide outside Nain, Labrador, on the Atlantic coast.

Paley’s accident occurred near the red line or in the gully a little to the right of it. Deception Pass lies behind the knoll marked in blue. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Legacy

The news spread quickly and caused deep shock in the mathematical community. Wiener was devastated, and he later wrote movingly of his friend’s warmth, humor, and brilliance.

The 1934 AMS Colloquium Lectures, originally awarded to Paley, were delivered by Wiener in his memory. The lectures formed the basis of the posthumous monograph that ensured the Paley–Wiener theorem reached a wide audience.

Paley’s mathematical ideas proved to be durable. The Littlewood–Paley theory underpins much of modern wavelet analysis. The Paley–Wiener theorem is taught in every serious course on harmonic analysis. Paley graphs and the associated combinatorial constructions continue to appear in coding theory.

At age 26, Paley had already achieved enough to be remembered as one of the outstanding lost talents of 20th-century mathematics, whose life ended abruptly in a single moment on a remote Canadian mountainside.

Raymond Paley’s grave in the Old Banff Cemetery. Photo: Wikiwand