Perhaps the most famous ship in exploration history, the Fram was designed specifically for the challenges of polar navigation. With her rounded hull, she withstood the crushing ice that shattered the likes of Shackleton’s Endurance, rising up over the ice instead of being pinned by it. Her design, however, which made her so perfectly adapted to her line of work, also made her roll horribly in the open sea, inducing seasickness.

The SS Bessemer was basically the exact opposite of the Fram. While she was engineered against seasickness, she also seemed to be engineered against seaworthiness. Or perhaps some jealous oceanic deity, seeing humanity attempt to conquer the limitations he’d placed upon their encroachment in his domain, cursed the poor ship.

Cursed or no, the SS Bessemer certainly had an eventful career.

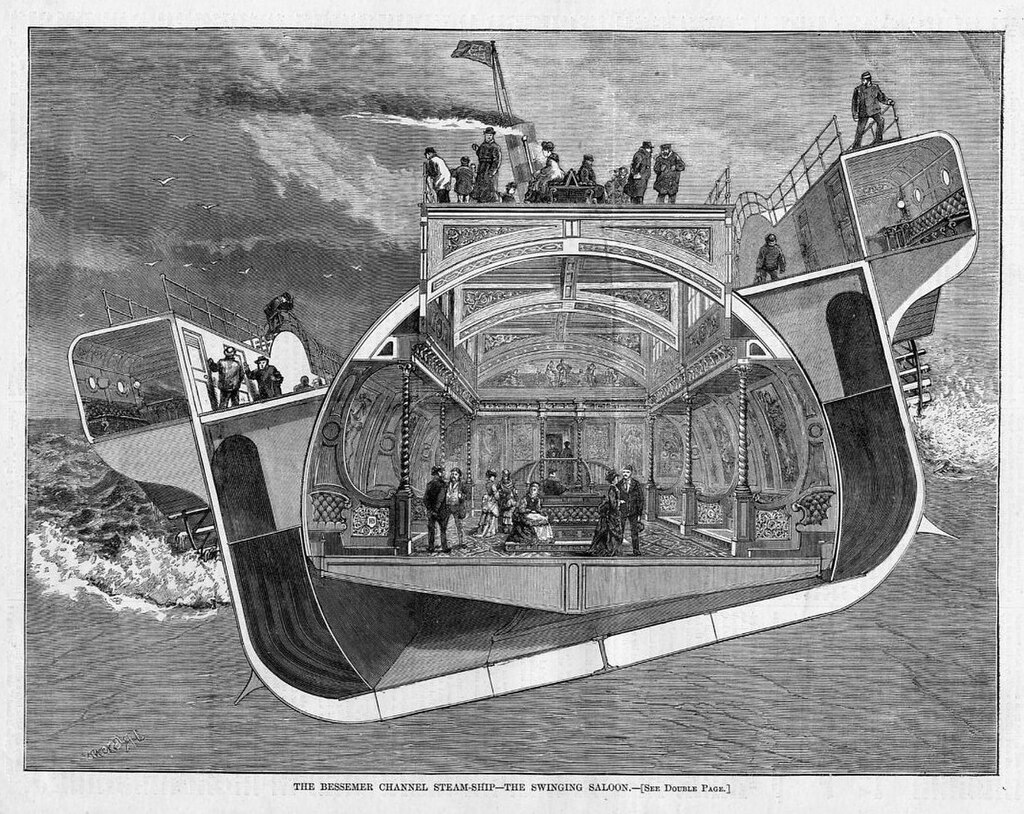

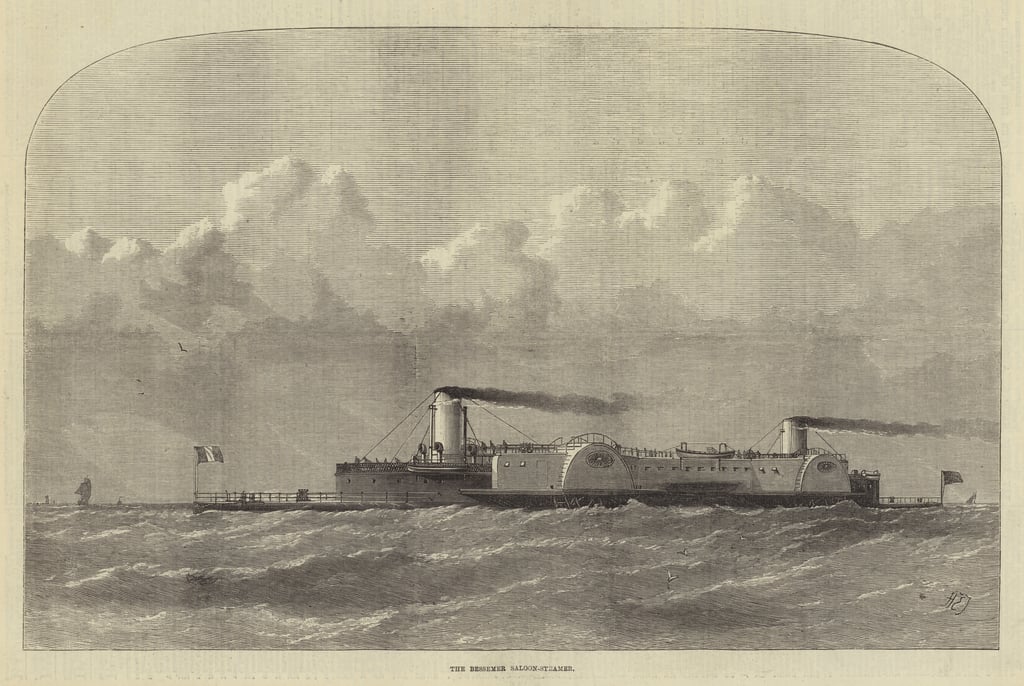

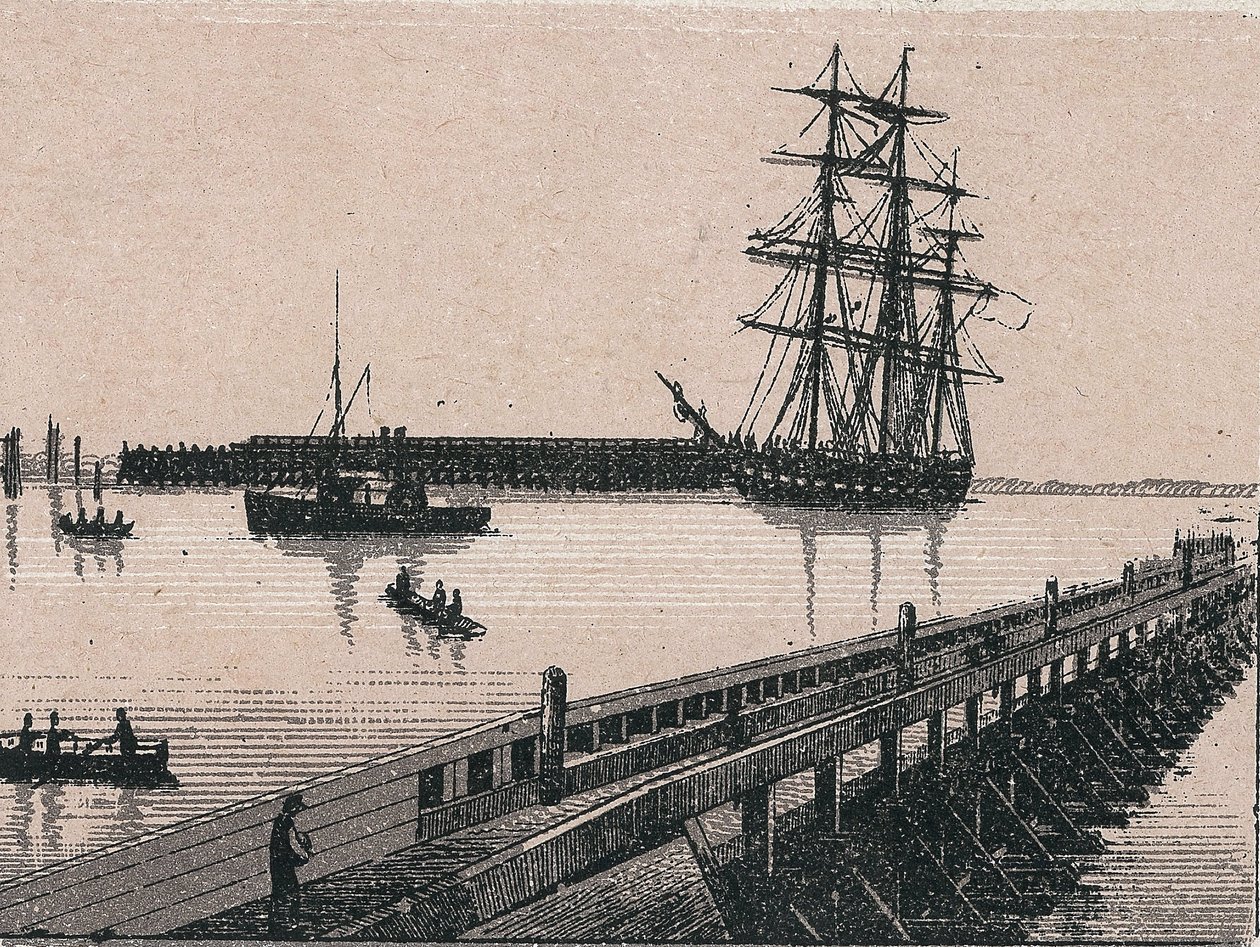

The SS Bessemer at sea, December 1872. Photo: Illustrated London News archive

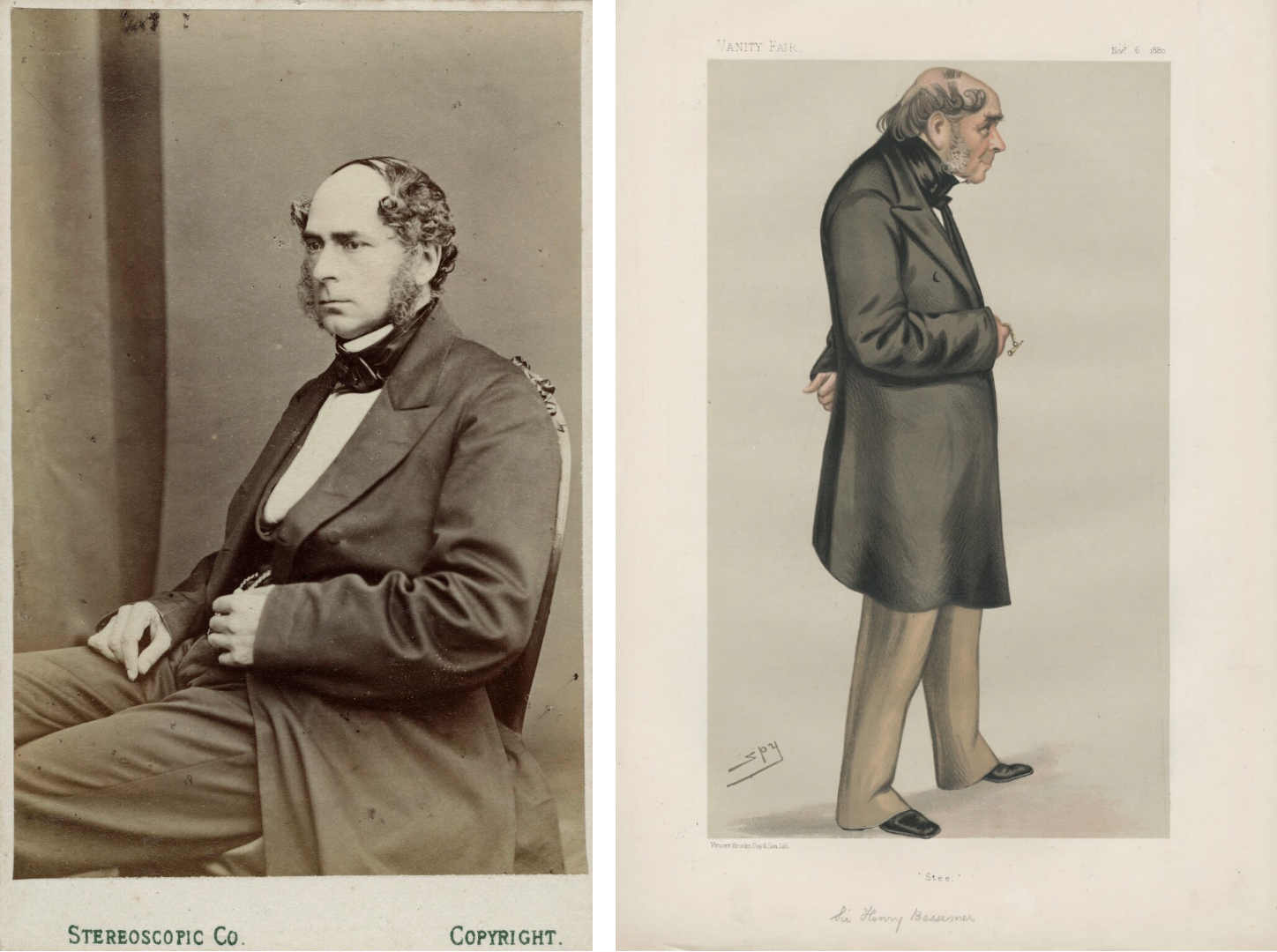

The eponymous Bessemer

Henry Bessemer was born in 1813 on his Huguenot inventor father’s small Hertfordshire estate. After fleeing the French Revolution, his father settled in England and made his money from his inventions. Henry took after his father, fascinated by machinery and driven to improve upon the mechanisms he observed. He moved to London at 17 to seek his fortune and immediately began experimenting.

His first big success was a steam-powered machine to manufacture bronze powder. Originally, his only ambition with the experiment was to make gold paint for his sister, a watercolor artist. But the process and manufacturing machines he developed made enough to support him while he continued inventing.

If you’ve heard the name Bessemer, you’ve heard it in connection with his most important invention: the Bessemer process. In terms of Industrial Revolution inventions, it ranks among the steam engine, the telegraph, and the spinning jenny.

What Bessemer invented was the first way to produce steel quickly and cheaply. Bessemer steel built the railroads, bridges and skyscrapers of the next century, and made Bessemer a wealthy man. But he wasn’t done inventing.

This 1917 painting by E.F. Skinner shows workers using the Bessemer process to manufacture steel. Photo: London Science Museum

The steel magnate and mal de mer

In 1868, Sir Henry (we will call him that moving forward, to avoid confusion between the inventor and his ship) took a channel steamer from Calais to Dover. While the English Channel crossing through the Strait of Dover, as this route is called, is and was very common, it wasn’t easy. While it took less than a day on the steamship ferries, the shallow channel with its powerful, strange currents was notorious for causing seasickness.

“Few persons have suffered more severely than I have from sea sickness,” Sir Henry wrote in his autobiography. The 1868 crossing, followed by a 12-hour train journey, left him temporarily bedridden and, it seems, somewhat traumatized. Determined to rid the world of this scourge, he set his inventive mind to work.

The principle was deceptively simple: A suspended cabin within the ship, which, mounted on gimbals, would remain stable while the outside of the ship was tossed about by the waves. He built a tiny model, “small enough to be placed on a table,” and rocked it back and forth using clockwork. It was probably rather adorable.

In December 1869, Sir Henry patented his design and set about building it.

Bessemer’s 1860s visiting card, left, and a caricature of him by Sir Leslie Ward. Photo: National Portrait Gallery

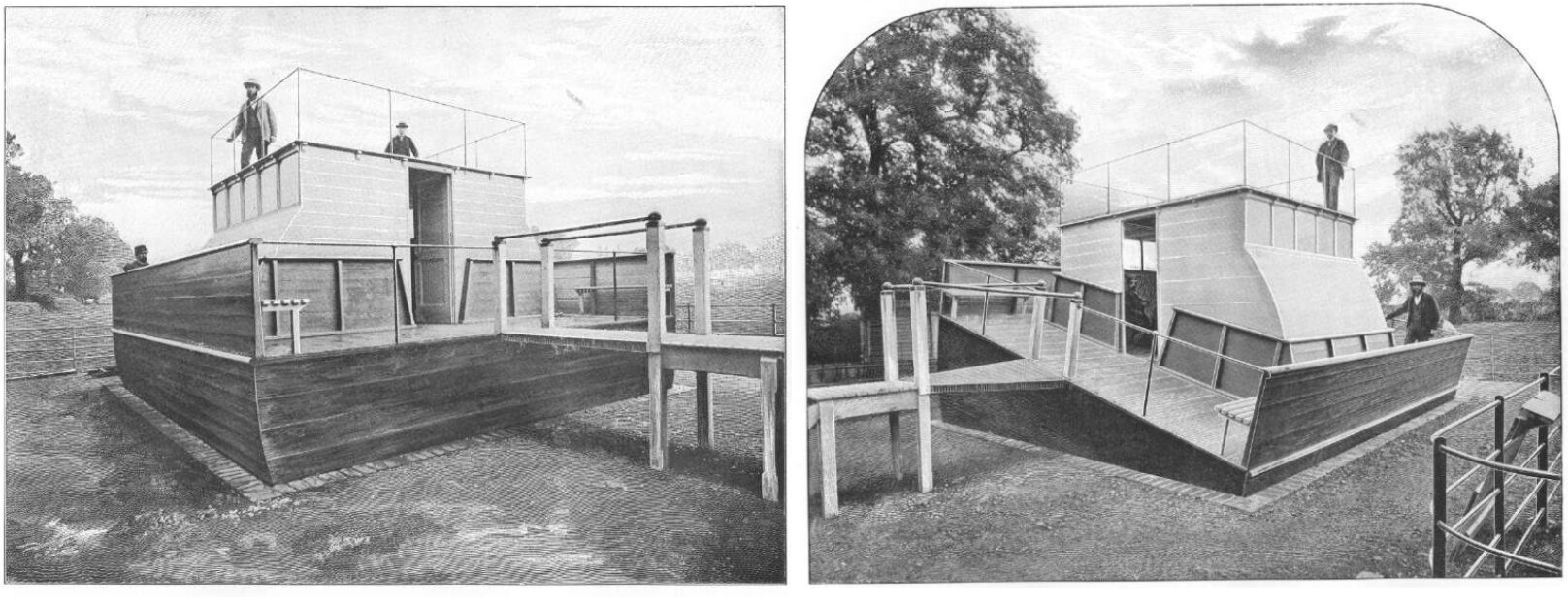

The backyard ship

Rushing into the project, Sir Henry paid a shipbuilder to construct a small steamer for the modern equivalent of over $430,000. No sooner had he done so than he realized he needed to alter his initial design, and the half-built ship wouldn’t accommodate the changes. He sold it off for a third of what he’d paid and instead built another model.

Sir Henry was unwilling to actually go out to sea for testing, so he built the middle of a small ship in his backyard. His new design included a steersman. He would manually adjust the level of the cabin by turning a handle to match a spirit level. The motion of the handle would then control the hydraulics.

Sir Henry invited scores of wealthy and prominent friends and fellow inventors to experience the model. They all pronounced it a success, and papers on both sides of the Atlantic reported excitedly that soon seasickness would be a thing of the past.

The model Sir Henry built behind his house. Left, horizontal, right tilted. Photo: Sir Henry Bessemer, ‘An Autobiography’

Building the SS Bessemer

This steersman design satisfied Sir Henry, who formed a joint-stock company and raised $340,000, roughly $34 million today. Joining him in the company was Sir Edward James Reed, who’d been the Chief Constructor for the Royal Navy, and would go on to become a railroad magnate and a member of Parliament.

Designing the ship part of the SS Bessemer was probably somewhat of a low point for him. He’d just bitterly resigned from his Naval command. Parliament had undermined and insulted him by funding the HMS Captain, designed by his detested rival Captain Cowper Phipps Coles, without consulting him. He had something to prove when he decided to join the ambitious new venture.

Sir Henry and Sir Reed sent their plans to Earle’s Shipbuilding Company in Hull. Sir Henry continued to bleed money into the project just to keep it afloat.

When the ship was nearly complete and was moored outside Earle’s Shipbuilding Company in Hull, a late October gale struck the coast. Too long to be anchored in the regular way, she’d been chained horizontally by both stern and head. As a result, her long side met the full force of the wind, and she was torn from her moorings and driven onto the muddy bank.

She escaped the embarrassing incident without major injury, and they were able to coax her back into the water and finish construction. Finally, after even more personal financial outlay, the ship was insured, and a commander, a Captain Pittock, was found. The maiden voyage of the SS Bessemer was scheduled for May 8, 1875.

Plans for the SS Bessemer, published in ‘The Penny Illustrated Paper,’ 1874. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A trying trial run

The company wisely decided to perform a trial run before the public debut in May. A few weeks in advance of the date, Captain Pittock took the SS Bessemer out of Dover, planning to dock at Calais and then return.

Unlike many maritime mishaps, weather could not be blamed for what followed. As Sir Henry himself described, the SS Bessemer approached Calais “on a beautiful calm day, in broad daylight, at a carefully chosen time of the tide, and with all the skill of the best Channel navigator.”

Whereupon she crashed into the pier. Her paddle wheels slammed into the pier, causing $3,800 in damages and destroying the paddle wheels. Captain Pittock had to go before the consul in Calais, where he swore that the ship simply “did not answer her helm.”

She was fitted with replacement paddle wheels, and Pittock managed to carefully inch her back out of the port and limp home to England.

Sir Henry and the company decided it was too late to postpone the May 8 launch. Instead, while the SS Bessemer was being repaired, her creator had the saloon fixed in place, completely defeating the whole purpose of its existence.

The port of Calais in the late 19th century, which the ‘SS Bessemer’ made a habit of crashing into. Photo: meisterdrucke

Failure continues

Without a doubt, Sir Henry was an incredibly intelligent man with a gift for metallurgy in particular. But he was not a shipwright. The balance of weight in a ship is both important and delicate. The holds of contemporary sailing ships were carefully packed and re-packed to ensure the weight was perfectly distributed. Getting this wrong could negatively affect the sailing abilities of even a very seaworthy vessel.

The SS Bessemer, built around an unwieldy cabin and hydraulics, was already not the easiest sailor. With a great weight constantly shifting the center of gravity, she was practically unsteerable, with dangerously unpredictable movement.

Worst of all, she wasn’t even seasickness-proof. Reporting on her maiden voyage, a Wisconsin newspaper wrote that while the design seemed to work in the bay, once she reached the open channel things went awry: “Pitched about by the raging sea, the cabin floundered wildly, and the passengers parted with their victuals as passengers have ever been wont to do.”

On her first journey from Hull, where she was built, to Gravesend, she gobbled up coal at an amazing rate. One passenger reported that the saloon itself moved as designed, but either due to mechanical or human error, it didn’t respond fast enough to actually negate the movement of the ship.

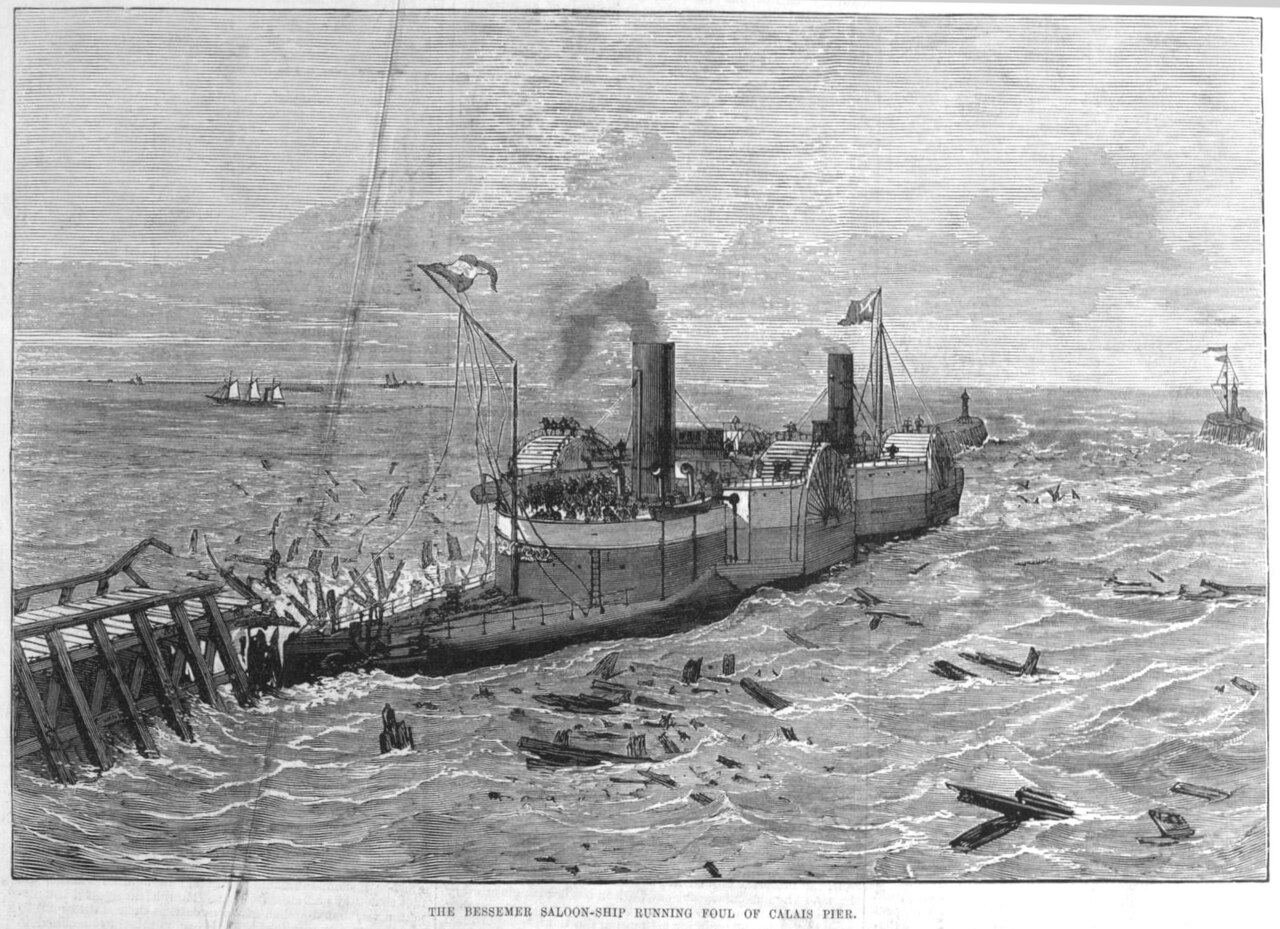

On the 8th of May, with the first passengers on board and just as ill as always, the SS Bessemer inched into the port of Calais. All breaths were held as Captain Pittock gave his orders– and the ship failed to respond. The SS Bessemer crashed into the Calais pier for a second time, as Sir Henry put it, “knocking down the huge timbers like so many ninepins!”

The SS Bessemer runs into the Calais pier, again. Photo: The Illustrated London News archive

The final demise of the SS Bessemer

Sir Henry had sunk a great deal of his personal fortune into developing, building, re-building, and rebuilding a second time. It was an unwillingness to throw good money after bad, not a lack of belief in the concept, that caused Sir Henry to finally pull the plug.

At least, that’s what he himself said. That his saloon had proved an entire failure, “nothing could be more absolutely untrue,” Sir Henry insisted. It’s almost sweet how much he believed in the viability of the wretched little ship despite all evidence to the contrary. At any rate, he never admitted that the concept itself was flawed.

But the second Calais incident killed the SS Bessemer commercially. The bankrupt Bessemer Saloon Steamboat Company was sold off, and the SS Bessemer was sold for scrap. Sir Reed had the saloon itself removed from the ship and installed as a billiards room on his estate in Kent.

Henry Bessemer continued to invent, with varying degrees of success. In 1893, he attempted to build a sun-powered furnace that he promised would reach up to 33,000˚C. However, he gave up after a lens maker failed to produce the required lenses.

In 1889, Sir Reed’s estate became Swanley Horticultural College, a women’s agricultural school. The beautiful, ornate saloon of the SS Bessemer was used as a lecture hall.

Students attend classes in the repurposed Bessemer saloon. Photo: Dave Greig/Victorian photo album

On March 1, 1944, Swanley Horticultural College was bombed in a German air raid. The saloon was destroyed by a direct hit. Only a few pieces of paneling, rescued by local residents, survive.

Humanity has yet to invent a seasick-proof ship, but we do have over-the-counter dimenhydrinate now, which has always worked for me, anyway.