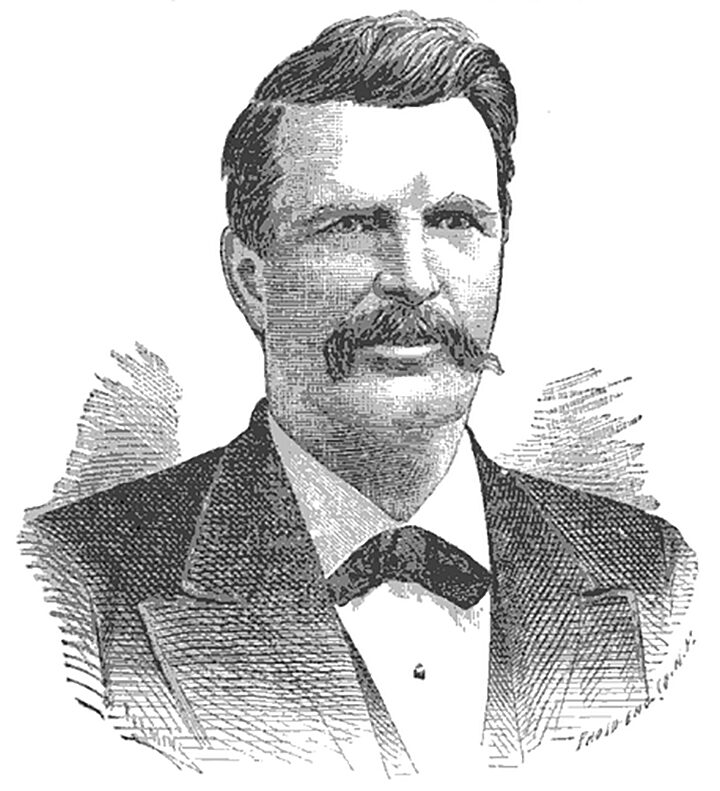

Henry Howgate was not himself an arctic explorer, but as an influential bureaucrat, he profoundly affected American arctic expeditions in the late 19th century. He was partly responsible for one of the worst disasters in arctic history. But the story of this charming rogue was much, much stranger.

Tall and good-looking, Howgate joined the Signal Corps — the new division of the army responsible for stringing telegraph wires across the frontier. At some point, he became friends with Adolphus Greely, a lieutenant likewise involved in the early Signal Corps.

Howgate lived in Washington with his wife Cordelia and daughter Ida. He put in long hours and eventually became responsible for dispersing the Corps’ funds. The head of the Signal Corps, General Albert Meyers, increasingly relied on his hard-working assistant, especially after Meyers became ill. When Meyers died, Howgate became the Acting Chief Signal Officer.

During his late office hours, Howgate started an affair with a woman in his office, a “fetching redhead” named Nettie Burrill. Nettie reportedly enjoyed the good things in life, and Howgate was happy to accommodate her by using his position to embezzle vast funds from the Signal Corps. It is estimated that he took between $400,000 and $500,000 from government coffers — up to $15 million in today’s dollars. He set Nettie up in a lavish house not far from where he lived with his wife and daughter. Every week, the six-foot-tall, flamboyantly moustachioed Howgate told his wife he had to travel for business and went off to live with Nettie for a few days.

Nettie Burrill was one of the first women to work for the U.S. Signal Corps. Illustration: Wikipedia

Arctic obsession

During his time at the Signal Corps, Howgate also became fascinated with arctic exploration. It overlapped with his work; the early Signal Corps was involved in a push to extend American influence into the Arctic. Inspired by the British Arctic Expedition of 1875-6 to northern Ellesmere Island, Howgate advocated for establishing a polar colony well north of where even the Inuit lived. The expedition would stay in the High Arctic for years, gathering scientific information and perhaps going to the North Pole.

He even drafted a bill to Congress about it, in a monograph called Polar Colonization. In it, Howgate listed several reasons why past expeditions failed. Most important of all, he wrote, was the men’s excessive dependence on the vessel they sailed north in. It created, he said, a “city of refuge” that made them “timid, unadventurous, and irresolute.”

Much better, he suggested, to drop them off by ship. The ship would then sail away but return to resupply them every year and pick them up at the end of their stint. He strengthened his case by asserting how easy it would be every summer for a supply ship to reach Lady Franklin Bay, the harbor on Ellesmere Island where the British had based themselves. This theory — like the armchair theory of the Open Polar Sea from earlier decades — had dire consequences later.

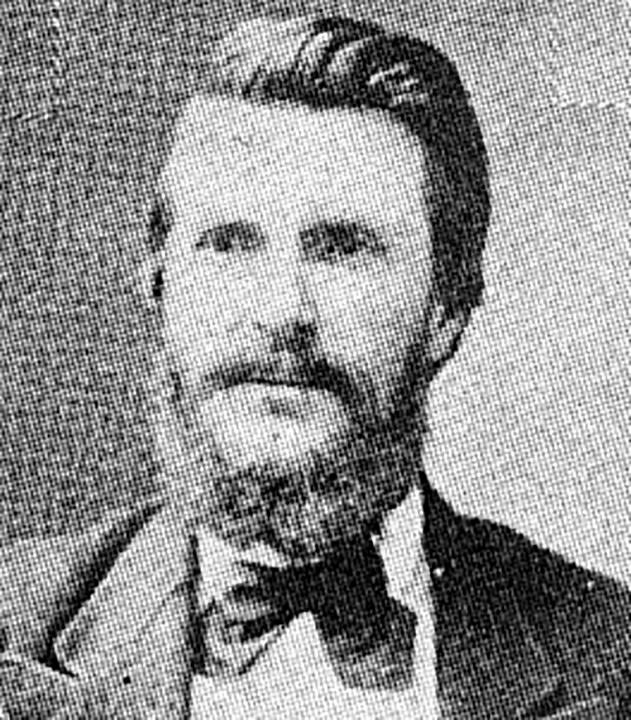

A bearded Henry Howgate. Photo: Public domain

Authorities close in

In 1878, Howgate tried to establish one such colony, but it fell through because of a faulty ship. Undeterred, the energetic Howgate pressed for an expedition to establish his dream colony during the first International Polar Year in 1881. It was likely not a coincidence that his old friend, Adolphus Greely, was chosen to lead that expedition.

Meanwhile, his embezzlement was catching up with him. Rumors circulated about financial irregularities in the Signal Corps, so when General Meyers died in 1880, Howgate applied to become the official Chief Signal Officer. This would allow him to bury his misdeeds indefinitely.

Although Howgate had strong support, he lost out to an even better-connected competitor. Eventually, President Hayes nominated William Hazen for the position. Knowing that Hazen would surely investigate the purported financial improprieties, Howgate resigned from the army three days later and fled to Michigan with Nettie.

By the time Greely left for Ellesmere Island in August of 1881 to establish this three-year scientific polar colony, Howgate’s crimes had become public. He was now a fugitive. Authorities traced him to Michigan through money that he sent regularly to his abandoned wife and arrested him.

Daring escape

While awaiting trial, Howgate lived comfortably in jail. His cell was furnished with items from both his Washington homes, and he could visit Nettie regularly under escort to take a bath, since washing facilities at the jail were not to his liking.

On one of these visits, his daughter Ida — in collusion with her father — kept the deputy marshal distracted with an hour-long piano recital while Howgate slipped out the back door into a waiting coach with Nettie. They boarded a ship down the Potomac, and the hunt for the escaped fugitive began again.

A period sketch of Nettie Burrill.

To the public, Howgate was a somewhat sympathetic rogue. Charm and chutzpah went a long way even then.

“When the news of his escape from custody was made known, there was a general feeling of gladness in the community,” reported the Washington Evening Star at the time. “Pretty nearly everybody had a sneaking desire that Howgate would never get caught.”

A dashing fugitive

Indeed, Howgate was much harder to catch this time. He went back to Michigan and worked as a reporter under an assumed name. A couple of years later, he moved to New York City and opened an antiquarian bookstore under the name of Harvey Williams (his middle name). He had long been a book collector, and back in his Signal Corps days, the funds that he did not allocate to Nettie’s upkeep went to accumulating one of the best private libraries in DC.

Robert Todd Lincoln, the eldest son of Abraham and now the Secretary of War, was affronted by Howgate’s brazen escapades. When the Secret Service failed to nab him, Lincoln hired detectives from the newly formed Pinkerton Agency and offered a $1,000 reward for his capture.

While this was going on, Greely’s polar colony on Ellesmere Island was wishing that, like every other arctic expedition, they had traveled in their own ship. A leased vessel, the Proteus, had successfully dropped them off at Lady Franklin Bay with supplies for at least two years. The following summer, the Proteus was to return with more supplies and mail from home, and to swap out personnel.

Arctic theory meets reality

However, Lady Franklin Bay was not as accessible as Howgate had theorized. While the ice of the previous winter reliably melted away, thick, multiyear pack ice flowed south from the Arctic Ocean down the narrow channel between Ellesmere Island and Greenland, often blocking the way.

Even today, only icebreakers dare venture in that area. About 20 years ago, a cruise ship tried and got stuck in the ice. It was just coincidence that a nuclear icebreaker was in the vicinity off northern Greenland and was able to free it.

In 1882, the Proteus couldn’t reach the polar colony because of ice. It tried again in 1883. It not only couldn’t reach Lady Franklin Bay; it was crushed in the pack ice some 300km to the south and sank.

Lacking a ship of his own, Greely was under orders that if no vessel reached them by late 1883, they were to work their way south in the small whaleboats they had with them. Presumably, they would encounter the Proteus eventually. In a decision that his men vehemently disagreed with, Greely insisted that everyone abandon the still well-stocked station and head south, as ordered.

The remains of Greely’s house in Lady Franklin Bay, Ellesmere Island. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Tragedy strikes

After a heinous two-month trip over broken, shifting ice, and with winter coming on, Greely and his men made it halfway down Ellesmere Island. There, a cairn note gave them the deadly news: The Proteus had sunk, and the sailors aboard had saved themselves by heading to Greenland in lifeboats. They had managed to leave only 40 days of supplies for Greely’s 25 men.

The walls where Greely’s men overwintered and died. A boat and tarpaulin topped the stone walls during their stay. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

No ship would make it there for at least another eight months. Eight months, with 40 days of food on a barren coast with the High Arctic winter setting in. How they must have longed for their own well-laden “city of refuge” now.

Their famous ordeal, in which 19 of the 25 died, mostly of starvation, is another story. A rescue ship finally reached them in June 1884. That six survived was a miracle. Although he was a skinny man at the best of times, Greely, incredibly, was one of the survivors.

Greely on the rescue ship after their ordeal. Photo: Public domain

Rare book dealer

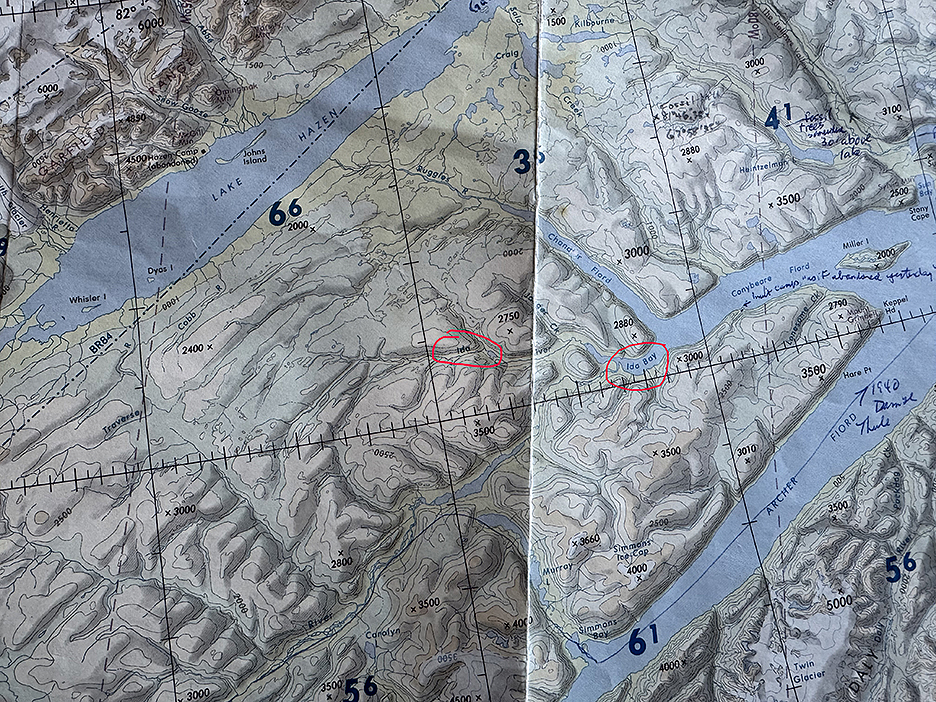

Meanwhile, the fugitive Henry Howgate remained at large as a rare book dealer in New York City. When Greely returned to Washington, General Hazen hit the roof when he saw that Greely had named several features on Ellesmere after his disgraced friend. Needless to say, Howgate’s name was purged from those places.

From hiding, Howgate cheekily wrote Greely to protest. If Greely couldn’t reinstate Howgate’s name on those geographical points, he argued, perhaps he could name something after his daughter Ida? Despite leading the most disastrous arctic expedition in U.S. history, Greely had become famous, America’s most celebrated polar expert, and a career officer on the rise. He didn’t respond to Howgate.

Adolphus Greely in his later years. Photo: Wikipedia

Captured

Howgate evaded detection for almost a decade. Then in 1894, A.L. Drummond, one of the Secret Service agents in charge of the original manhunt, retired and moved to New York to open his own detective agency. Coincidentally, he heard about a tall, distinguished rare book dealer who frequented many local auctions. Drummond recalled that Howgate was a bibliophile and began to suspect that this might be their elusive fugitive, especially when he heard that the grey-bearded book dealer lived with an attractive, much younger woman.

Drummond confronted the suspect as he emerged from his bookshop. “How are you, Captain Howgate?” he asked.

Howgate didn’t try to deny it. “Yes, I’m Howgate,” he admitted. “I’ll go with you. I’m beat.”

He was taken back to Washington, where the ever-faithful Ida posted his bail. He lived with her while awaiting trial. His old charm seemed not to have failed him, and he was initially acquitted. But at a second trial on follow-up charges, he was found guilty and sentenced to 15 years. He was 60 years old.

In 1900, after five years in prison and in failing health, Howgate was paroled. He died soon after.

His old friend Greely lived decades longer and became a celebrated general. Two features on northern Ellesmere Island, Ida Bay and Ida River, are named after Howgate’s daughter.

Map of northern Ellesmere Island, showing the features named after Howgate’s daughter Ida. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko