“It’s a savage mountain that tries to kill you,” American alpinist George Bell said of 8,611m K2. Bell was speaking in 1953, after he and his climbing partners nearly died while attempting the first ascent of the world’s second highest peak. In the years since, K2 has often flashed its savage side. One of the most famous disasters came in the summer of 1995, between August 13 and 15.

We will examine the 1995 K2 disaster in a two-part series, with part two coming tomorrow.

A history of tragedy

K2 saw its first ascent in July 1954. But the first fatality came much earlier, on July 30, 1939 (Dudley Wolfe). From the first ascent until the end of 1994, 113 climbers summited K2, and 38 died.

In August 1986, 13 climbers died, five of them during a week-long storm.

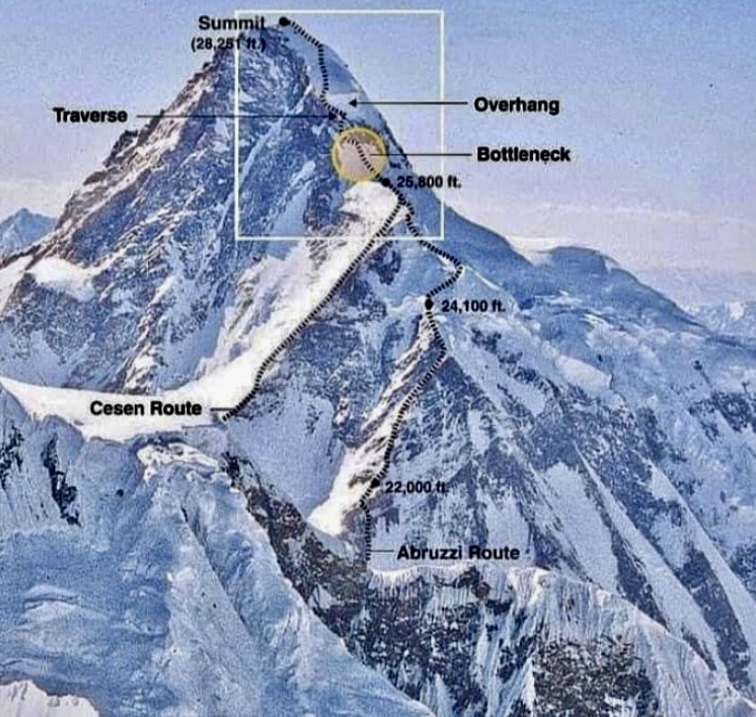

In the summer of 1994, five more died, including three Ukrainians: Dmitry Iszagim-Zade, Alexandr Pazkhomenko, and Alexei Khazaldin. While the three mountaineers were on their summit push, the weather turned. They never returned. Several days later, their teammates found Pazkhomenko and Khazaldin’s frozen bodies at 8,400m. A German team found Iszagim-Zade’s leg stuck in the snow near the Bottleneck.

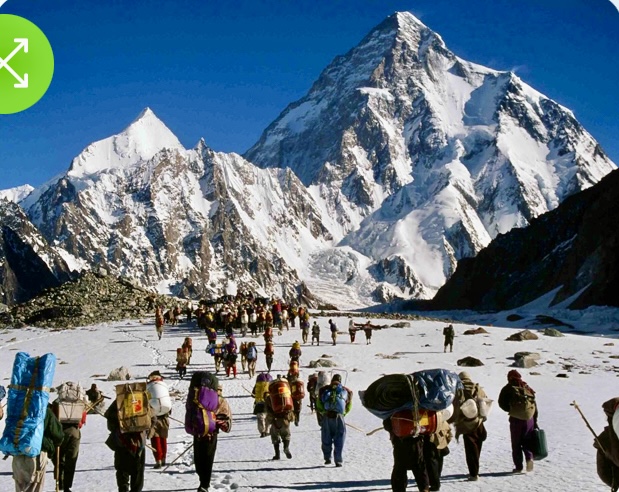

K2. Photo: Shutterstock

The 1995 teams

In the summer of 1995, seven expeditions targeted K2. Six of them headed to the Pakistani side of the mountain, and one party approached from China.

A German expedition led by Peter Kowalzik attempted the North Ridge of K2 from Tibet. During their summit attempt on July 25, a major storm hit when they were above 5,000m. Avalanche danger forced them to turn around.

After five days, the weather improved and they started to climb again. On August 5, Kowalzik’s team reached Camp 4 at 7,900m, but early the next morning, another storm hit. Again, they had to retreat. While descending, Jay Sieger fell nine meters but was not seriously injured. Kowalzik’s team then called off the expedition.

The Northwest Ridge on K2. Photo: John Shen

American attempt on the Northwest Ridge

An American party led by Larry Hall made their Base Camp on the Savoia Glacier. They had almost no contact with the teams using the usual K2 base camp site. Hall’s expedition wanted to climb the Northwest Ridge.

In 1991, Frenchmen Pierre Beghin and Christophe Profit followed the Northwest Ridge, diagonally traversed the Northwest Wall, and finally followed the Japanese North Ridge route of 1982. They reached the summit on August 15, 1991, without supplemental oxygen. Although they climbed minimal new terrain, they climbed the top section of the route in alpine style, without fixed routes or established camps.

By June 27, Hall’s seven-member team had set up Camp 1 at 6,000m.

Moving up to Camp 2, Hall was hit by a falling rock and sustained two broken ribs. They reached Camp 3 on July 17, and a two-day storm started.

“We were hampered all summer by two-to-three-day storms and major wind,” John Culberson wrote.

After the stormy weather, they made a summit attempt on August 2. The team reached 8,100m but turned around in deteriorating weather. More snow fell, and they descended, hampered by avalanches and deep snow. On August 5, they made it to Camp 1 before continuing to Base Camp and ending the expedition.

The Cesen and the Abruzzi routes on K2. Photo: Team Ali Sadpara

Teams on the Cesen Route

The Cesen/Basque Route is on K2’s south-southeast spur. This route leads to the Shoulder at 7,600m, and from there, it shares the same route to the summit as the Abruzzi Route (Southeast Ridge).

The Cesen route was first attempted by a French-German party in 1981 and then by a U.S. team in 1983. Both had to turn around before reaching the Shoulder. In 1986, Tomo Cesen reached the Shoulder and descended to Base Camp via the normal (Abruzzi) route.

Finally, the Cesen route was completed to the summit in 1994 by Basque climbers Juanito Oiarzabal, Juan Tomas, Kike de Pablo, and Felix and Alberto Inurrategui. The Cesen is now the second most frequently climbed route on K2.

In 1995, two Spanish teams tried the Cesen Route. The first, a seven-person team led by Pepe Aced, reached 8,300m on July 5. But while descending, Jordi Angles fell in the dark. He dropped 1,000m to the foot of the mountain. It was the first fatality of the season.

The second party from Spain was led by Jose Garces. They arrived in Base Camp at the beginning of July, when Aced’s team were already at 7,000m.

Almost all of Garces’ strong seven-man team had experience on 8,000m peaks. They progressed well before their summit attempt. On August 1, they pitched Camp 3 at 7,100m and continued to around 7,400m before turning around on August 3 in bad weather.

The large Dutch team head to Base Camp. Photo: Nkbv.nl

Successful Dutch ascent

Another of the 1995 teams, a Dutch party led by Ronald Naar, succeded on the Abruzzi route. On July 17, Naar and Hans Van Der Meulen (who climbed without supplemental oxygen) reached the summit accompanied by high-altitude porters Mehrban Shah and Rajab Shah. British climber Alan Hinkes also summited with them. Hinkes had planned to climb with Alison Hargreaves, but during the first weeks on K2, they went their separate ways.

Two more teams

Two other teams wanted to ascend the Abruzzi Route. One was an expedition from New Zealand led by Peter Hillary (son of Edmund Hillary), and the other was an American/British party led by Rob Slater that included Alison Hargreaves.

“Leaving Alison Hargreaves at K2 Base Camp with the American expedition, I returned home with an uneasy feeling, almost a premonition, that a disaster was going to happen,” Hinkes wrote in the Alpine Journal.

Alan Hinkes on the summit of K2. Photo: Yorkshire Post

A three-team summit push

After a prolonged period of bad weather, six climbers from Garces’ Spanish team started from Base Camp at 9 pm on August 9 for a final summit attempt. They split into two groups, eventually reuniting in Camp 3 on August 11.

Not feeling strong enough for the final attempt, Manuel Anson descended to Base Camp. Garces, Javier Olivar, Javier Escartin, Lorenzo Ortas, and Lorenzo Ortiz continued.

The U.S.-British party led by Slater made several aborted summit attempts in the poor weather. On August 6, porters arrived to help several members of the team hike out. But Slater elected to stay and make another attempt, along with the team from New Zealand. Hargreaves, who almost gave up her attempt, decided at the last minute to stay and climb with Slater and the Kiwis.

Peter Hillary’s five-member team included Kim Logan, Bruce Grant, Matt Comesky, and Canadian Jeff Lakes.

K2. Photo: Seven Summit Treks

After climbing during the night, the five Spanish climbers mounted the Shoulder and, at dawn, set up Camp 4 at 7,950m. On August 12, at about 10 am, they were visited by Slater, Hargreaves, Hillary, Logan, and one more climber who arrived via the Abruzzi Route to scout the upper slopes.

With favorable weather conditions, they arranged for a joint attempt the next day at midnight. After their meeting, the visitors descended to their lower camp, and the Spaniards tried to get some sleep.

The final push

At midnight and in good weather, all the climbers started their final push.

From Base Camp, the summit looked clear.

One member of the Spanish team, Ortas, didn’t feel well. He decided to stay in Camp 4. The Spanish party headed up, assuming the other group would join them later.

One hour after the Spaniards left Camp 4, Slater, Hargreaves, and Grant went past Ortas’ tent, hoping to catch the Spaniards before the Bottleneck.

Later, but still before dawn, members of the New Zealand team also arrived at Ortas’s tent. Hillary asked Ortas’s permission to get into his tent to warm up a little. Canadian Jeff Lakes was also pushing for the summit, but Logan and Comeskey stayed in their Camp 4.

Garces returned from the summit push long before the Bottleneck. On his way down, he met Slater, Hargreaves, and Grant. A little later, suffering from cold feet, Garces reached Camp 4. Hillary and Lakes were still there, using one of the Spanish tents. Soon after, Lakes and Hillary set off for the summit.

The giant overhanging serac above the Bottleneck on K2. Photo: Naila Kiani

Hillary troubled

At noon on August 13, there were eight climbers between 8,200m and 8,300m ascending slowly up the Bottleneck and out across the exposed traverse.

But still at the foot of the Bottleneck, Hillary was worried.

“I was troubled by the weather. An ominous bank of cloud had blanketed western China and had drifted up against the northern boundary of the Karakoram Range. The northerly wind was driving towers of rising cloud up over K2, and as it drifted over the summit, periodically obliterating my view of the mountain, it would sweep the flanks with showers of falling snow,” Hillary recalled.

Hillary decided to abort, but Lakes said he would continue for a short time to see if things improved.

Meanwhile, in Base Camp and the lower parts of the mountain, a harsh wind picked up. According to radio conversations between the Spanish team and Base Camp, Hargreaves saw that the weather was deteriorating but thought there would be enough time for everyone to reach the summit.

The three Spaniards climbing toward the summit reported that the weather was no different than the previous day, with the usual build-up of daily clouds temporarily enveloping parts of the mountain. They reported at noon from 8,400m that it was clear on the far Chinese horizon and perfectly windless.

Jeff Lakes before the storm on K2. Photo: Peter Hillary

On Sunday afternoon, Hillary descended to Camp 4. Later, Lakes also aborted his summit push and arrived at Camp 4. According to Ortas and Garces, Lakes looked tired. Ortas and Garces gave Lakes something to drink, and Lakes continued descending by the Abruzzi Ridge.

While the small group of international climbers were approaching the summit, wind increased in Camp 4.

The summit

On August 13, Ortiz contacted Base Camp by radio, asking what time it was. It was 6:23 pm. Asked where they were, Ortiz answered: “Too late, we are on the summit.”

There was joy, although their colleagues in Camp 4 and Base Camp were starting to worry about the late time and the changing weather.

Ortiz and Grant were the first two to top out. Soon after, at 6:30 pm, Olivar called to say he and Hargreaves had also summited. He added that Slater and Escartin were very near the top, coming up slowly. Olivar said it was extremely cold but windless and that all four (Grant, Olivar, Hargreaves, and Ortiz) were about to start their descent. Because of the late hour, they would not wait for Escartin and Slater.

The Abruzzi Spur. Photo: Pakistan Tourist Board

Hurricane winds

While the summiters started to descend, sometime between 8 and 9 pm, hurricane-force winds hit Camp 4, still occupied by Ortas and Garces. The situation began to get very complicated.

It was a dry wind blowing from the north, and Ortas and Garces were struggling. Garces’s tent was about to be blown away. With Ortas’s help — he held the tent with bare hands — Garces jumped out at the last minute. The two climbers lost their gloves, and by 11 pm, they also had to abandon the other tent. They were forced to find shelter by lying against the bases of the blown-away tents, waiting for dawn.

Hilary and Lakes, moving at different speeds, had a nightmare descent. The summiteers, already descending but much higher on the mountain, were in real danger too.

We continue their story in Part II here.