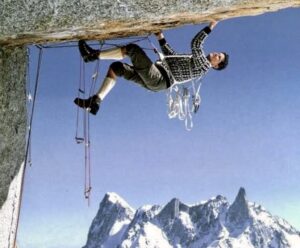

I dare to publish a story, a true story written by my rope-mate/husband about what it is climbing for him. Also, it reflects his feelings about 2 serious climbing accidents he already had during his 29 years as a climber. From the last one, on 21 December, he’s still recovering, but one can tell he has a climbers’s soul 🙂

Nine months went by since the accident.

A small piece of a sedimentary stone, created many million year ago waited patiently. On the 21st of December 2014, my left hand decided to grab it. A simple act, a simple gesture and…all the fore coming plans changed drastically, violently.

The stones do not think, they’re just there. After all these months I find myself wondering if that small piece of the planet was already meant to be detached of its position on that day. One small piece of stone detached flied to the ground, taking me with it in its inevitability. For the stone, falling to the ground meant nothing, but for me…

The fall was short, not much more than 2m, but it was unexpected. The crash was hard. I felt it violently and immediately I understood it was serious. I screamed and moaned like a child. I cried. I felt fainting. Would my time had come? Did my hour come? THE HOUR? The anxiety left me dizzy and suddenly, the lack of air…

The gear was still perfectly organized in my harness. I didn’t have any time to place a single protection between me and the ground. One meter higher and probably nothing would’ve happened. It was a ridiculous climbing fall, short and inglorious.

João Gaspar hugged me, doing all he could to comfort me to tranquilize me. Fernando Pereira had already grabbed the phone to call 112 (Portuguese emergency number). Between crying and panic I raged with myself. My thoughts travelled among multiple images, none of them pleasant: “How could you let this happen? Again…”, “112, ambulance, hospital…”. I thought of Daniela, the pain she would feel…again. I thought of my mother, the sorrow I would cause her…again. I thought and thought again, breathless. Still in João’s arms, I heard him say repeatedly: “Don’t sleep, don’t sleep!” – I felt grateful for having a friend there, so close – but I didn’t sleep.

With my eyes shut, I remembered to breathe, deeply, rhythmically. After long minutes the panic gave place to deep, rhythmic breaths. Sometimes I was taken by anxiety and the irrational would take over me. On those moments, I felt fainting. But slowly, I would come back.

I heard Daniela’s voice, she had already been crying, I knew it. She hugged me, kissed me and told me a few words to calm me down. At that time I had already made the “check-up” to myself: move the toes, feel the legs. “They’re not numb!” “That’s good, that’s good…!”

Hours at the hospital. Exams to check for fractures. The prognosis was not totally bad. Two lumbar vertebrae fractured but without hurting the marrow, a micro-fracture in the basin and one (“non-important”) fracture of the metatarsal bone of the little finger of the left foot.

Forecast: three weeks lying on a bed, then wheelchair, then transition to crutches, then transition to a single crutch then relearn how to walk, then…

Daniela’s parents, Maria da Luz and Antonio Teixeira, to whom I will be forever grateful, gave me their room and bed. For two months I became the main guest in their house.

Teresa Leal and João Gaspar became the tireless and always present friends who helped in all kind of tasks… I know that I will never be able to pay this huge gratitude…friendship debt.

Daniela became from one day to the next a professional nurse, dedicated, supportive and caring. Doctors coincided in the opinion that I should lie down and move as little as possible. The most dramatic of being bedridden were the “non-visits” to the toilet. I felt the main character of a tragic comedy. The problem was that the play involved the life rhythm of everyone around me. And Daniela was always with me, always cherish, always present. The days passed, long and endless. They turned into weeks.

—–

The first “walk” out of the house in the wheelchair was celebrated on a Coffeshop near the house. While Daniela went inside to get two coffees, I enjoyed the clouds crossing the sky. I always liked the clouds. Although I was in an urban environment, that little piece of nature brought me some encouragement. The clouds are excellent metaphors of freedom. They are formed wherever; they do not obey to any rules and they travel where they want, following the flavour of the wind. They fly free above all countries, above of all people. That first time I went out of the house after the accident, carried me to one of those ephemeral moments of freedom. Its ironic how sometimes the bad experiences of life are the ones that awake us to the small details, those that really matter. In a brief moment, I joined the clouds, en route to an uncertain horizon.

The physiotherapy sessions accompanied my first steps, and walking with a pair of crutches became part of my routine. Months went by. This was not my first climbing accident, the first occurred almost 25 years ago. From that accident I had physical memories, but not a great deal of psychological traumas. It was such a long time ago. The time has its own magical touch to smoothen all things. An enormous pain becomes a remote memory, present, but digestible. Time teaches us to live with our own demons and ghosts.

From the accident back in 1992 I don’t remember the physical pain; it vanished as the years went by. What I keep in my mind is a lesson, a decision. I was young and my dreams flowed at a frenetic rhythm. The existential doubts the same. At that time, the two broken legs in an ice fall in the Pyrenees forced me to think deeply about the consequences of following a dream. Was it worth to climb mountains?

According to the surgeon that placed the six screws that I still have on my ankles, I “would never be able to climb again”. Today, strangely, I almost forgot the post-surgery pain. What I do clearly remember are the tears I cried in that hospital bed, on the following night after hearing the words the surgeon told me.

An old belief in alpinism says that you have five years to decide what you really want. Meaning, during those five years one is always asking himself if all the sacrifices, the efforts, and above all, the risks, are really worth it. “Is this what I really want?”. According to the belief, after five years either you give up, or alpinism gets into your blood, like a chronicle disease from which you cannot escape anymore.

In 1992, I had little more than five years of alpinism. I was at the edge of taking the supreme decision. “Keep doing it or not?”. I didn´t have to offer myself a meteoric fall in plain winter, on the famous “Gaube Couloir”, to question my compromise with alpinism. Still, there I was, laying down in a hospital bed, with a lot of time to think about life and dreams.

I just cried for one night and then my decision was taken. The surgeon could “go to hell with his fucking opinion!”

——

Now I found myself facing the same dilemma. I would willingly dispense this new lesson. Lesson?

In 1992 I learned several lessons and took crucial decisions that in a certain way changed the course of my life. But now, after more than two decades, honestly, I cannot figure out what is the lesson to be learned. I have much more experience than in those years, I climbed in all possible imaginable terrains, I feel much more cautious, and my ability to analyze the risk in the mountains is infinitely superior. Still, the “burden” of my experience did not prevent the accident. The fall occurred in the beginning of the route and it could’ve happened in any sport climbing route, immediately before reaching the first bolt.

This time I didn’t recognize any mistake, I didn’t place the protection incorrectly (I didn’t even have the time for it!), I was not distracted (I think), I wasn’t climbing in a terrain I felt uncomfortable with…and it happened!

I can only conclude that the more one climbs, the bigger are the chances for something to happen! Maybe that’s it. Perhaps the grand designs of fate, the ones that we look for, when serious things happen, are summarized to a simple fact, so tasteless, as realistic.

Daniela Teixeira on the South face of Kapura, while we climbed the new route “Never Ending Dreams”. In a distance, a sea of mountains in the Himalayas, all there waiting to be explored.

The truth can well be dictated by a giant Russian roulette that spins until randomly stopping, in somebody’s name, without taking in account anything like experience or beliefs.

“Climbing is risky”, “Climbing is dangerous”, “You can die climbing”…so, why keep doing it? Why dedicate your life to something that might kill you?

The truth is that I don’t have a convincing answer for this question.

“Convincing?!” Then again, who am I trying to convince if not my own self?

This new accident that could’ve kill me or (worst) placed me in a wheelchair forever, made me reflect a lot about the consequences of some of our choices and directions we take. We can think, believe and insist that those are OUR CHOICES, OUR WAY, but the truth is that our decisions will affect those who are close, our beloved ones. And when I think of it (like it happens now, while I’m writing) I feel confused. In this mental turmoil, one thing seems certain: trying to justify my choices with logic and reason seems like an impossible task. Time taught me that it’s useless to try to find reasons to justify why we climb rock walls and mountains, for those who simply do not feel any sympathy for these activities. In the extreme eventuality of an accident occurring, trying to offer an explanation based in logic it’s absolutely ridiculous. All we can babble sounds like a stupid excuse and we always get the feeling that the listener turns his/her back muttering “He´s crazy!”

Maybe I choose to go on because for me, climbing and alpinism are components of an art form, a powerful combination between the beauties of nature, adventure and philosophy. A tangle of very difficult concepts to explain. Something to which I hold on tight, to appease a certain feeling of guilt for dragging others, especially those who are close to me and have to live with the consequences of my actions. The distress on Daniela’s face when she saw me prostrated on the ground that December afternoon, bounces in my brain and ends down on my stomach, where all tension always accumulate. What to do then? It is an unanswered dilemma. Words are not enough.

The Himalayan wind blows plumes of snow from the crests of the mountains. The magnificent silhouette of Shivling dominates the landscape. Far in the distance stands Meru. Behind my left shoulder, not far away, I can see the massive bulk of Bhagirathi. The base camp plateau is covered by a blanket of freshly fallen snow. Daniela is sitting in lotus position in meditation, facing Shivling. The silence is total, only disturbed by a gentle breeze that raises thousands of snow crystals that sparkle when being pierced by the light of the sun. Here, one can smell peace. The mind empties. The mountain…we are part of it. We are part of something grand. We are mere dust of stars but like the mountains, we have become the most important element of all. We and the world. We are the mountains! It is impossible to explain these simple but simultaneously complex emotions with words. I look again to the icy peaks … a small black crow passes by, floating gracefully in the air, and suddenly, without even taking consciousness, I end up discovering what I seek. In a blink of an eye, I can foresee the reason…my reason.

After months without climbing a rock, Daniela and I returned to our dear Serra da Estrela. Little by little, the balance, the rhythm of life slowly returns.

I’m still not 100% ok, and honestly, I think I will never be. I will content myself with a good 90%. I will feel happy to be able to return to the world of high altitude climbs, with more or less physical pain.

In the meantime, we are back to exploration climbing and have already opened a few rock lines. Interestingly, on the wall, I feel very stable and calm. Apparently the accident didn’t have any impact on my confidence. It is possible that the mental training that I forced myself to do while recovering (“You shall not be mentally affected. You shall not be mentally affected!”) helped to achieve this state of mind.

I suspect however, that the fundamental reason for the apparent tranquillity while climbing, is the simple acceptance that “this” is what defines me. “Accept and live well with your decision! “

——

The cloud disappeared from sight, hidden behind a gray building. The cloud is free, it does not respect borders, it is part of a whole much more important, it is a part of the planet, of nature and all beauty’s. Maybe that cloud will reach the mountains, or maybe not. The cloud is free … Daniela arrived with the coffees. I look at her and intimately I feel thankful for knowing love. Shortly after, I’m again pushed home in the wheelchair. I feel peaceful…

… I saw the cloud.

Paulo Roxo