For a time, Thomas Simpson was considered the man who would have discovered the Northwest Passage, if he had lived long enough. Today, he is relatively little known, but when he is remembered, it is for his death. Murder, suicide, madness, a notebook full of secrets — five men entered the wilderness, and only two returned. Who shot first? And why?

This lithograph depicts Thomas Simpson reaching Victoria Land in the Canadian Arctic. Photo: Willy Stower, around 1903

How Thomas Simpson turned explorer

Simpson, born in Dingwall, Scotland in 1808, was not a boy anyone expected to explore the Arctic. He was a delicate, sickly child, described by his brother Alexander as having “a quiet, tractable temper, and [paying] a steady attention to his studies.”

By the death of his schoolteacher father in 1821, Simpson was already destined for the church. At 17, he enrolled in King’s College, Aberdeen, and graduated with an M.A. with high marks. He kept at his studies, but Simpson had run into a common problem for M.A. graduates who wish to keep studying: He lacked the funds.

Simpson had hoped to go to medical school, but couldn’t afford it. Continuing in the church meant years of supporting himself as a tutor before he could get a parochial assignment. Besides, naturally resentful of authority, he was beginning to stifle under the strict, traditional Church of Scotland.

His elder half-brother, Aemilius, had joined the Hudson Bay Company in 1826, and his brother Alexander had signed up in 1828. They had a family connection; their cousin, Sir George Simpson, had recently become the Governor-in-Chief of Rupert’s Land (a British territory in the Hudson Bay drainage area of Canada). Sir George’s career is murky; he joined the Hudson Bay Company as a clerk in 1820. In 1826, following internal and external disputes that cleared out the executive suite, he became Governor.

Sir George offered his cousin the post of secretary to the company. Thomas, who had grown out of his sickly childhood constitution into heartiness and strength, agreed.

Sir George Simpson, a consummate businessman and opportunist, hired Thomas as his secretary. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Early success and early trouble

Simpson took to the adventurous outdoor life. With his cousin, he toured the southeastern holdings of the Hudson Bay Company in a light canoe. He spent the next several years traveling around the Canadian Arctic in George’s employ.

Simpson distinguished himself early, guiding a party of nearly a hundred recruits through the wilderness with far fewer desertions than usual. A year later, he took a party of men and dogs over 1,100km from York Factory to Red River. He told his brother Alexander that he loved the 28-day snowshoe journey, enjoying the fresh air and exercise.

Already, however, interpersonal conflict plagued him. Sir George was not an easy man to work for. Thomas Simpson reportedly found him “wavering [and] capricious,” calling his cousin “a severe and most repulsive master.” He was unimpressed with most of his colleagues, but assured Alexander that they both would soon have the prominence and success that they deserved.

Sir George Simpson’s canoe, where he and his secretary traveled on business. Photo: Royal Ontario Museum

A notable incident

Most of the lower-level employees of the Hudson Bay trading posts were indigenous people from several groups and people of mixed white and indigenous descent. Simpson frequently expressed a low opinion of them. When Alexander came to visit Red River in December 1834, he found his brother at the center of a small-scale race war.

One of the mixed-race Canadian workers had entered Simpson’s office and requested an advance on his wages. We don’t have the worker’s side of the story, but Simpson claims the man was drunk and disorderly and refused to leave when his request was denied. According to Thomas, the man put up physical resistance when he tried to remove him, and they got into a fight. Simpson won, beating the man badly.

The local indigenous community reacted badly to the incident and began demanding that Sir George punish Thomas Simpson. Simpson, meanwhile, told his brother that he feared an attempt on his life and believed the indigenous people planned to use the incident as an excuse to launch a full-scale rebellion.

Sir George met with representatives of the community and negotiated a rapprochement. Sir George paid the aggrieved party a small sum, handed over a barrel of alcohol, and apologized. He promised to remove Thomas from the settlement, which both parties seemingly understood he was not actually going to do.

Relations returned to normal, but Thomas remained convinced the indigenous workers were out to get him. He slept alone with barricaded doors and a guard dog.

Part of the Red River Colony, mid-19th century. Photo: Archives of Manitoba

The Dease expedition

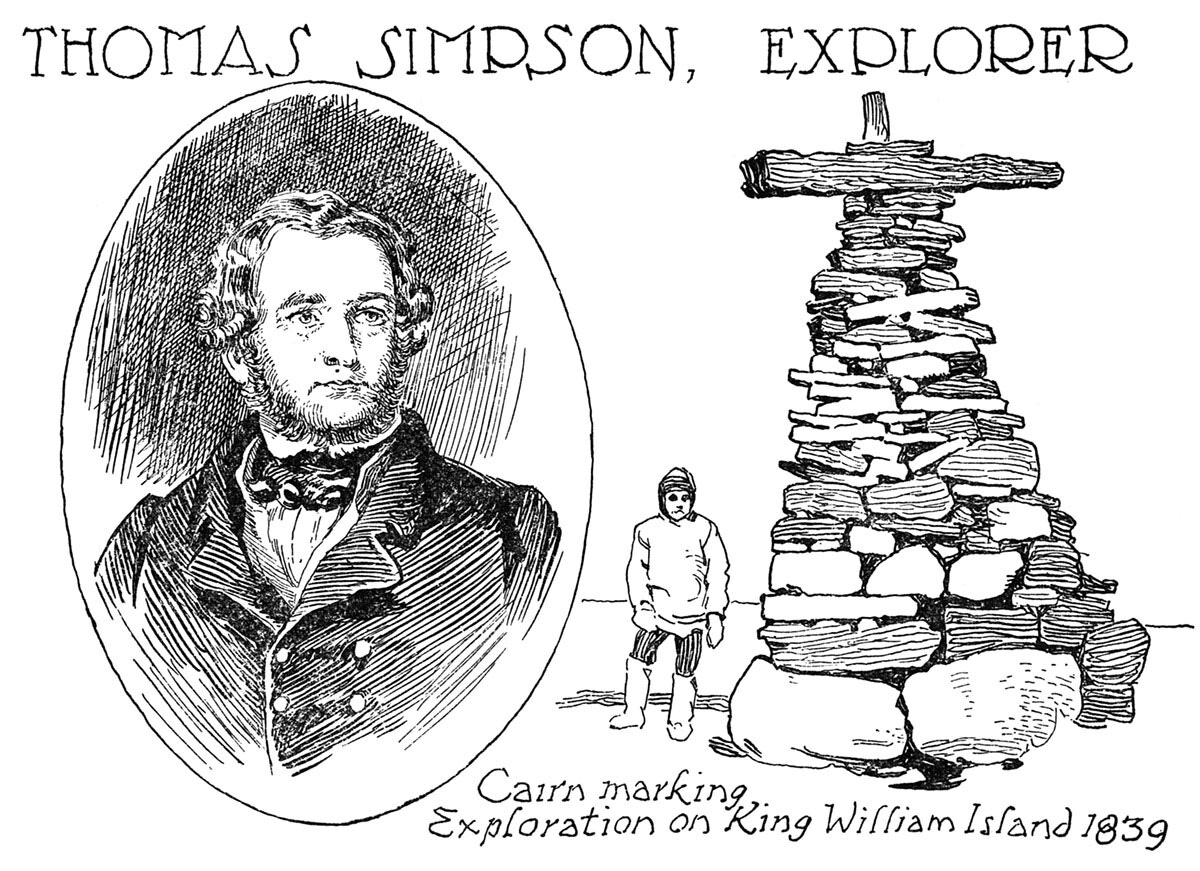

Thomas Simpson’s day in the sun came in 1837, when he became the second in command of an Arctic expedition. The Hudson Bay Company charter from 1670 included “finding the Northwest Passage” as a primary goal. So far, they had done little.

The expedition leader was 46-year-old Peter Warren Dease, the long-time chief trader and former John Franklin collaborator. What he lacked in qualifications, he made up for by being well-liked. Naturally, Thomas Simpson hated him. The leadership position, he was sure, was meant for him, and his cousin had spurned him at the last second.

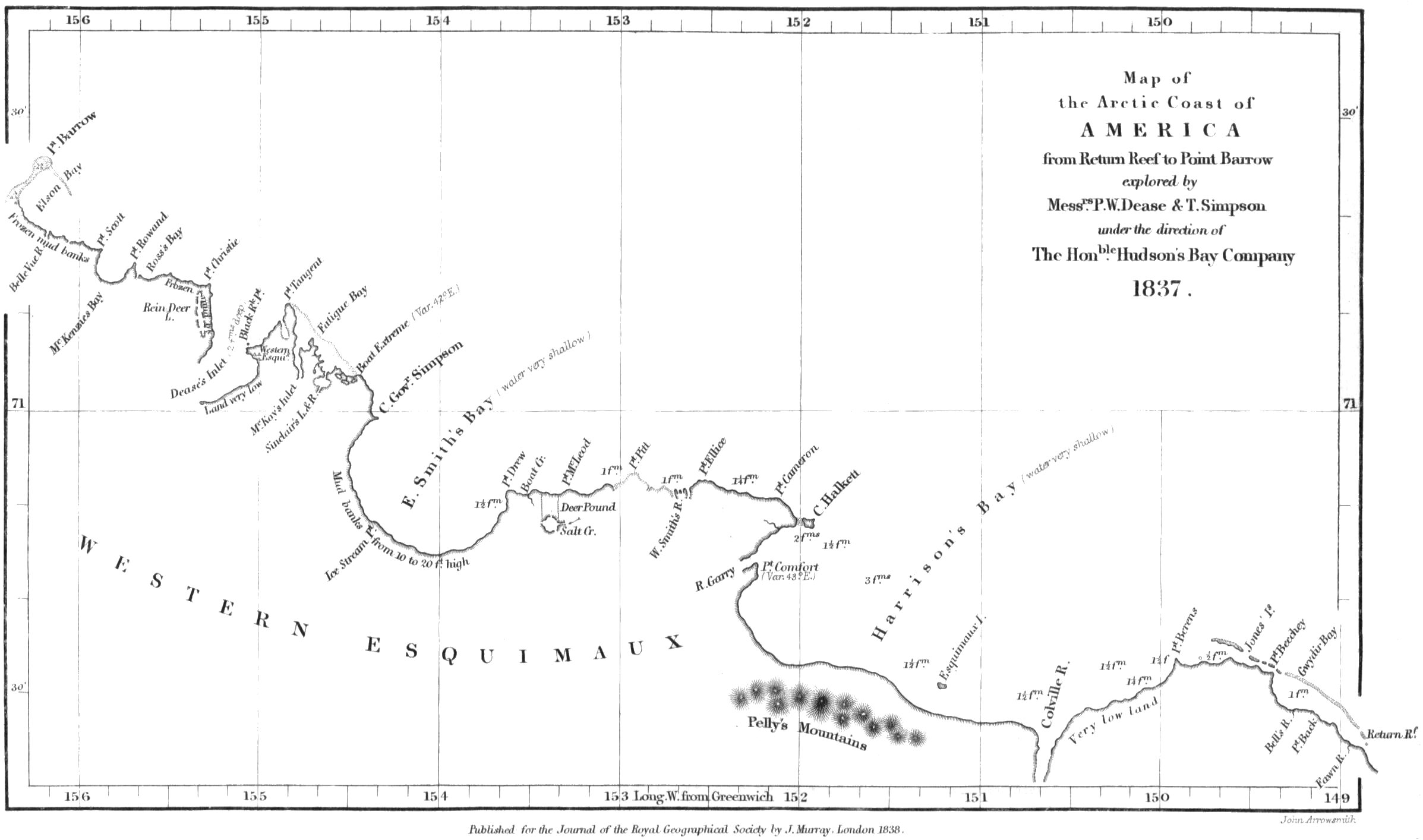

In only 62 days, Simpson made an over 2,000km overland journey to meet Dease at Fort Chipewyan. With 12 men, they had set out on June 1, intending to fill in the gap between Franklin’s Return Reef and Point Barrow, Alaska. By July 23, the party had eclipsed Franklin’s furthest west, set in 1826. But by the end of the month, the ice grew too thick to proceed further.

The boats, trapped by ice, were still nearly 100km from Point Barrow. Undeterred, Simpson set off on foot with five of the men. The party ran into a group of Inuit and borrowed their umiak, a small open boat. In this vessel, they reached Point Barrow, completing the “west” part of the Northwest Passage.

In a letter to Alexander, Simpson wrote that “I, and I alone, have the well-earned honour of uniting the Arctic to the great Western Ocean.”

Point Barrow, Alaska, also known by the Inupiaq name Nuvuk, appears frequently in the annals of Arctic exploration. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Few gaps remain

Dease and Simpson’s parties reunited and made their way back to Fort Norman by the start of September. There, they found instructions for the next stage of their explorations, up the Coppermine River.

Simpson spent the winter nursing a growing hatred of Dease and a conviction that their leader was contributing nothing. Dease was an “indolent, illiterate soul,” Simpson wrote.

In 1838, the expedition attempted to push east from Point Turnagain by boat. Again, the ice trapped their boats, and again, Simpson continued on foot, exploring a further 160km of coastline. The next year, conditions improved, and they traveled up the Coppermine River to the Boothia Peninsula. If they could find passage to the Gulf of Boothia and from there connect with the Atlantic, they would complete the Northwest Passage.

But it was too late in the season. Simpson had already harried them forward despite Dease’s wishes and the men’s exhaustion, forcing them up through the already freezing-over Mackenzie River. This was where Simpson claimed one of his most notable exploratory feats, that of naming Victoria Land (now Victoria Island).

By late September, the expedition was back at Fort Confidence. Simpson’s account of the expedition, published posthumously, provides much detail for readers willing to overlook all the self-congratulation.

A map of progress along the coast during the Dease expedition. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

One more expedition

Simpson no doubt felt that one more expedition would make him the first man to complete the famous, deadly passage. But they would not go back next season: Dease wanted to take his leave in Europe and have time off to marry and settle with his fiancée, a Métis woman named Elizabeth Chouinard.

Simpson did not have time for his loathed coworker’s domestic bliss. He petitioned Sir George for full command to continue the work. “Fame I will have, but it must be alone,” he wrote.

Sir George, possibly still concerned with his cousin’s personal issues, was reluctant. There was a tangled back and forth of letters, and for several weeks, Simpson refused to leave Fort Simpson for Red River as ordered.

Eventually, Simpson petitioned the board of directors in London. Worried that Dease would get there first and take all the credit, and wanting to make his petition in person, Simpson decided to go to the board himself. Simpson took his notebook, with many of the important observations and maps from the past three years.

In June 1840, he set out with four Métis men for the port of New York by way of St. Paul. He never returned.

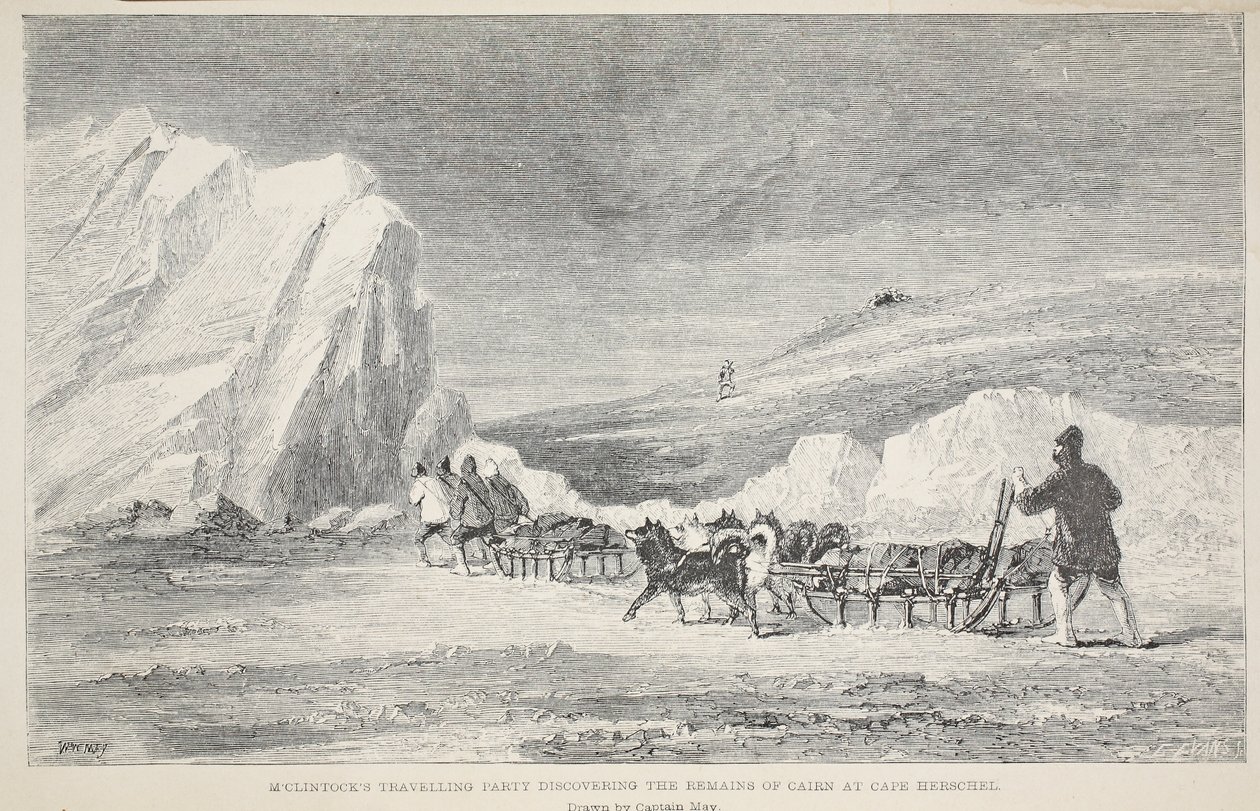

A cairn left by Thomas Simpson and Peter Warren Dease at Cape Herschel was rediscovered in 1856 by Leopold McClintock, searching for the lost Franklin Expedition. Photo: Elisha Kane

The final journey

In another letter to Alexander, Simpson said that the journey would be good for him; his stomach had been bad, and his spirits had been low all spring. The five men soon fell in with a group of several dozen people moving from Canada to the United States. For several days, they traveled together, but then Simpson, citing the need to move as quickly as possible, pushed on ahead with the four men from Red River.

On June 15, two of the party — James Bruce and Antoine Legros Junior — ran back into the group of emigrants. They had a frightful story.

After eight days on the trail, Simpson had begun feeling sick and insisted they stop, wanting to return to Red River. John Bird and Antoine Legros Senior began setting up camp when Simpson fired his shotgun at them. Yelling that they planned to kill him, Simpson fired two shots, hitting first Bird and then Legros Sr. Bruce and Legros Junior, the son of the elder Legros, quickly leapt onto their horses and rode off for help.

The men urged the party of emigrants to follow them back to camp and capture Simpson. Six men agreed and cautiously followed the pair back to their camp. Robert Logan, one of this party, later gave an official deposition on the scene they found by the banks of the Turtle River.

The banks of the Turtle River, a tributary of the Red River. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Simpson’s death

The eight men halted about 180m from the camp. They called Simpson’s name but received no answer. They could see the abandoned cart, the bodies of John Bird and Antoine Legros, and Bird’s dog lingering by his late master. The group moved a little to one side, hoping to get a different angle. Then a shot rang out, and a bullet “whistled over [their] heads,” from the direction of the camp.

All was quiet for some minutes, and the investigators decided to fire into the air in that direction, presumably to warn Simpson of their presence. Two men, Gaubin and Michel Rochette, fired, Rochette accidentally winging the dog, which ran off. Then all the party members fired twice and waited.

Finally, Rochette mounted his horse and did a quick ride-by of the camp, returning to report that he had seen Simpson lying on the ground, apparently dead. The men entered the camp.

Simpson’s body was “stretched out, with one leg across the other, and the butt end of his double-barreled gun between his legs, the right hand, with the glove off, directed to the trigger, the left hand, with the glove on, holding the gun, near the muzzle, on his breast.” He was missing the top of his head.

That was how Robert Logan reported it. But another of the party, who was deposed a few months later, described Simpson’s body as “lying with his face downwards, near, but not on, a blanket,” by the cart.

Legros’ body was under a blanket, with a pillow under his head. Bird’s body was a few steps away. They buried all three bodies.

Murder, madness, mystery

The question of Simpson’s final hours is twofold: Who fired the shot that killed him, and why did he shoot John Bird and Antoine Legros?

James Bruce repeated his story in an official deposition at St Peter’s, Iowa. The court never deposed Legros Jr, possibly in consideration of his age or family tie to one of the victims. The official verdict the court pronounced was “murder and suicide while of unsound mind.” Simpson had killed the two men in a fit of paranoid delusion, then shot himself.

Perhaps Simpson was an early and unrecognized case of so-called “polar madness.” Douglas MacKay, an early 20th-century historian of the Hudson Bay Company, argued that Simpson’s letters revealed “a rapidly mounting and almost uncontrolled egoism, the culmination of unbounded ambition and the lonely Arctic winter.”

We must acknowledge the role racial prejudice played in the incident at Turtle River, and the speculation that followed. Simpson distrusted his indigenous coworkers and had a history of conflict with them.

He was probably jealous of the fruits of his exploration and had admitted to suffering physical illness and a depressed spirit in the months before his death. That this paranoia and instability would become violence, directed at his Métis companions, is not necessarily out of character. It’s also not out of character for 19th-century fur traders to believe that indigenous people were thieves, murderers, and liars.

Adam Tollefsen went to Antarctica on the ‘Belgica’ and famously went mad. Photo: De Gerlache Family Collection

The official story contradicted

Alexander Simpson refused to believe it. In his biography of his brother, Alexander laid out a number of flaws in the official story.

Alexander asserted that his brother was an obsessive diarist and would certainly have had a notebook with him at the time of his death. But when his brother’s papers, recovered from the body, were delivered to Alexander, no diary was included. He also noted that his brother’s pocket map did not quite line up with the timeline given in the depositions. His foremost objection, however, was that his brother had never exhibited any signs of mental instability.

Remembering the events of December 1834, he believed the indigenous workers at the Hudson Bay Company in Red River had held a grudge against his brother. Both Simpsons were suspicious of “the evil passions of [their] race.” John Bird, in particular, was “dangerous,” according to Alexander, and believed that Simpson’s notes contained the secret of the Northwest Passage.

Alexander believed that his brother had gotten wise to the men’s plan to murder him for the documents and had feigned sickness to return to Red River. But over two days of travel, tensions mounted, and on June 14, Simpson killed Bird and Legros in self-defense, sustaining mortal wounds in return. The shot reported by Robert Logan and his party was, Alexander argued, imagined or invented.

The sudden end of his career today overshadows Simpson’s explorations. Photo: Library and Archives Canada

Continuing speculation

Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson dedicated a lengthy section of his 1938 book, Unsolved Mysteries of the Arctic, to Simpson’s death. He proposed another alternative to the initial murder-suicide theory.

He posits that, rather than being independent agents after his notes, Bird and the Métis were assassins hired by Sir George. Sir George, Stefansson posits, may have been motivated to prevent the Northwest Passage discovery to protect the Hudson Bay Company’s monopoly on the fur trade. Sir George would also have had the opportunity to remove the diary from Simpson before sending anything to Alexander.

It is worth noting that Stefansson was, as Roald Amundsen so neatly put it, “the greatest humbug alive.” But the humbug does admittedly have a point that Sir George’s diary, on the date he received news of his cousin’s death at only 31 years old, devotes more time to the taste of whitefish (“somewhat the flavour of trout”) than to the death.

There is also a third possible answer to the question of who shot Simpson. If the investigating party had been firing low enough to clip Bird’s dog, could one of the many shots — they all shot twice — not have hit Simpson?

Whatever the truth, the events of June 15, 1840, ended Thomas Simpson’s exploratory career. Would he have gone on to discover the Northwest Passage? Did this bizarre murder-suicide indirectly doom John Franklin and his men? We will almost certainly never know the truth.