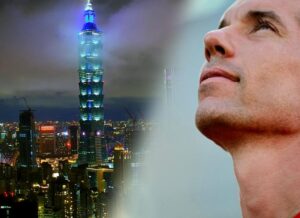

When Netflix recently announced that Alex Honnold would attempt to free solo a skyscraper live in Taiwan, it felt like the modern version of an old story. Before him, Alain Robert, the “French Spider Man” scaled glass towers across continents, chased by police and paparazzi alike. But many decades before either of them brought urban climbing into the mainstream, a more introverted breed of climber was free soloing buildings through the night.

They weren’t athletes or professionals. They were students at the University of Cambridge in England, sneaking out of their dorms and night-time curfew to climb the roofs and spires of their colleges.

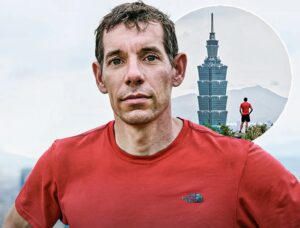

Their exploits were immortalized in the 1937 book The Night Climbers of Cambridge written by the pseudonym “Whipplesnaith.”

A later republication of The Night Climbers of Cambridge

The beginnings of a secret sport

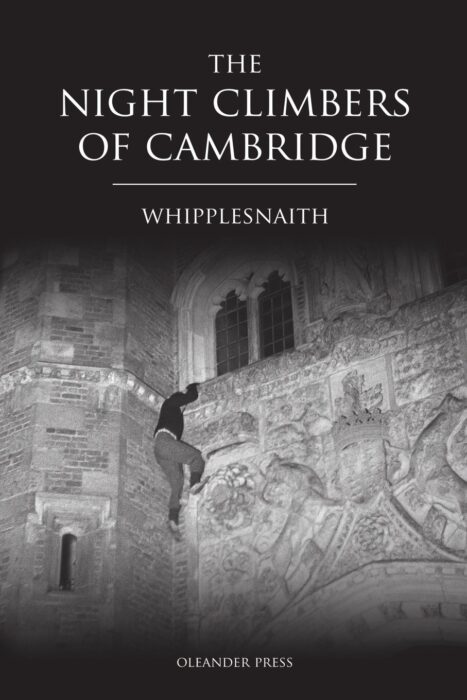

In the late 19th century, Cambridge may have lacked mountains or real rock to climb, but it was, in a sense, a kind of vertical playground. Mountaineer Geoffrey Winthrop-Young published The Roof-Climber’s Guide to Trinity [College] in 1899, a slim, privately circulated book that mapped the college’s architecture as a series of routes.

His idea was mischievous but not mad, as the university’s chimneys, gargoyles, and parapets provided the perfect outdoor climbing gym without leaving town.

A modern version of Winthrop-Young’s classic

By the 1930s, a new generation had taken up the challenge. The group, which later called themselves the “Night Climbers,” operated late at night, moving in silence across the city’s skyline. They scaled the buttresses of King’s College Chapel, traversed the pinnacles of St John’s College, and leapt across the Senate House gap.

Part of their motivation was perhaps simple curiosity and a bit of disobedience. Cambridge was at the time a place of tradition and strict rules, and climbing its walls no doubt became a quiet rebellion.

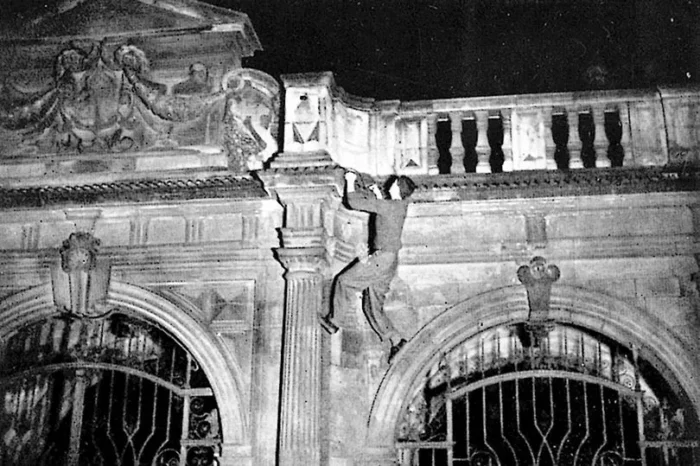

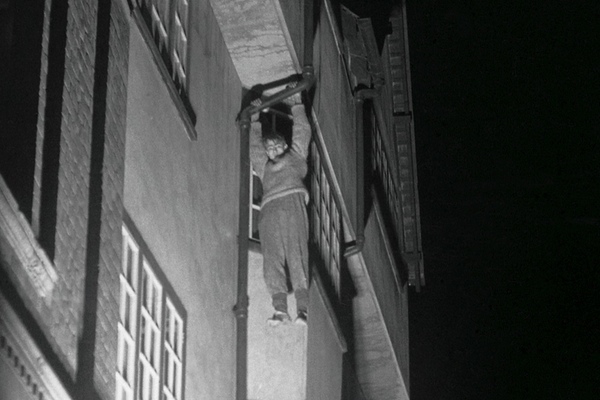

A possible image of ‘Whipplesnaith,’ high up on King’s College Chapel. Photo: Oleandar Press

The 1937 book that emerged from these adventures combined deadpan instruction with photographs that were surreal. Shot with flash at night, the images show ghostly figures clinging to the ornate facades of Cambridge’s most hallowed buildings. Their faces are indistinct, their poses seem awkward yet composed, suspended somewhere between grace and danger.

Around the same time, the Night Climbing Society at Oxford University was also nocturnally clambering up buildings both at the University and in the wider town.

Climbing without ropes

The climbers wore plimsolls for grip and quietness. Ropes were rarely used. They moved with deliberate care, and presumably would have rehearsed routes in their mind during daylight from below, memorizing the angle of each stone and the texture of each ledge.

“As you pass round each pillar,” Whipplesnaith wrote, “the whole of your body except your hands and feet is over black emptiness.”

Climbing on Pembroke College. Photo: Oleandar Press

The colleges’ Gothic architecture, with its spires, chimneys, and cloisters, offered hand and footholds unlike any cliff face. The night added another dimension. It removed the chance of any audience and must have eerily heightened every sensation.

Not just Cambridge and Oxford

Night climbing wasn’t confined to Cambridge. Similar traditions took hold at other educational establishments across the UK, particularly in private boarding schools where steep slate roofs and stone courtyards offered their own temptations.

One participant was the late Arctic scientist Geoffrey Hattersley-Smith, who attended Winchester College as a teenager in the late 1930s. In an unpublished memoir, he recalled how climbing the roofs became a kind of relief from academic pressure:

“I found it a particularly good relaxation to wander the roofs, when I was working rather hard for the scholarship and rising at 6 am each morning to revise my physics and chemistry,” he wrote.

Geoffrey Hattersley-Smith in later years. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Hattersley-Smith also described one close call from his school days:

“There was a memorable occasion when I was climbing with Christopher Longuet-Higgins on the roof of the Museum in the early hours of a morning in summer 1941. Christopher was about to glissade on his bottom down the roof, until I warned him that he would face a considerable drop down the end.”

That warning likely saved his friend from a serious fall. Longuet-Higgins went on to become a Royal Society Professor, while Hattersley-Smith himself explored the polar regions as a glaciologist, geologist, and yes, a climber. Among other first ascents in both the Arctic and Antarctic, he summited Ellesmere Island’s Barbeau Peak, the highest mountain in North America east of the Rockies.

Winchester College Chapel, right, and Scholars’ College, left, where George Mallory was a scholar between 1900-05. Photo: Wikipedia

Hattersley-Smith also noted that one of the forerunners of night climbing at Winchester College later became a mountaineer of some repute.

“A most notable predecessor had been George Leigh-Mallory of Everest fame. He is said to have displayed his prowess to a visitor by chimneying up a corner of the Middle Gate of Chamber Court.”

Real danger

The risk was real, whether at Cambridge or elsewhere. “If you slip, you will still have three seconds to live,” Whipplesnaith wrote.

“Your feet are on slabs of stone sloping downwards and outwards at an angle of about thirty-five degrees to the horizontal, your fingers and elbows making the most of a friction-hold against a vertical pillar, and the ground is precisely one hundred feet directly below you.”

Photo: Aperture.org

Several climbers were caught by porters and narrowly avoided expulsion. In later decades, others weren’t as lucky. In the 1960s, one student was reportedly “sent down” after being photographed mid-ascent.

Some continue

The tradition didn’t totally die with the 1930s generation. The practice of buildering (urban climbing) is a common pastime of University climbing clubs in the UK, though perhaps not with the same daring as the night climbers of old.

Nonetheless, a 2025 feature in Varsity, a Cambridge student newspaper, describes climbers still scaling the University skyline. Not surprisingly, some of the climbs tend to occur around the time of the student balls.

Cambridge student Rebecca Wetten climbed the Faculty of History building in her May Ball gown. Photo: Rebecca Wetten

University authorities, of course, disapprove. Trespass can lead to fines or disciplinary action, and modern safety measures such as alarms and cameras no doubt make the practice harder than ever.

Yet the allure seems to persist, as nobody thinks to look up!