First, let’s set the scene with some background on Makalu:

At 8,485m, it is the fifth-highest mountain on Earth. Frenchmen Lionel Terray and Jean Couzy first climbed Makalu on May 15, 1955. Six more members of the expedition followed in the next two days. They all used supplemental oxygen.

The first ascent without bottled O2 was made by 25-year-old Marjan Manfreda of the former Yugoslavia on October 6, 1975. He went via the South Face. He did not intend this to be a no-O2 ascent, but his gear malfunctioned. His six companions, led by Ales Kunaver, used bottled O2.

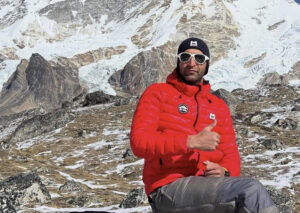

Karl Egloff and Nicolas Miranda on their recent speed climb of Makalu without O2. Photo: Nicolas Miranda

Until 2019, a total of 568 people summited Makalu, 240 of them without supplemental oxygen. Forty-eight people perished on its slopes, including 37 who did not use O2.

Along Makalu’s normal route. Photo: Adrian Ballinger

Routes

As on many mountains, the first summiters sought out the easiest route, although we must point out that no route on an 8,000’er is easy. Their successful ascent followed the Makalu La to the Northwest Ridge.

This later became the normal route, where most climbers go. It is a long way, and its last section, leading through the French Couloir, is the most complicated. Once past this section, you reach the top of the eastern ridge. From there, you climb to the top.

Apart from the normal route, the mountain features 12 other routes, which were opened gradually in different years. Some of these include variants.

The West Pillar of Makalu. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

The West Pillar

If we look at Makalu, our eyes immediately see a spectacular pillar. The West Pillar is aesthetic, wild, complicated, and dangerous. A very exposed route, especially in Makalu’s frequent strong winds. Technically, it is a very difficult line.

Two French climbers, Bernard Mellet and Yannick Seigneur, made the first ascent of the West Pillar on May 23, 1971. They were members of a team led by Robert Paragot.

In total, more than 20 expeditions have tried to climb the West Pillar, either completely or as part of their route. Some of them were successful via the pillar itself, others managed to reach the top by deviating from the pillar.

A closeup of the West Pillar of Makalu. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

Thirteen expeditions attempted the entire West Pillar. Seven succeeded, after enormous difficulties. The failures happened mostly because of bad weather, poor conditions on route, avalanches, falls, or even exhaustion. One 1989 expedition even had to give up, frustratingly, at 8,350m because they ran out of gear for the final section of the mountain.

The successes

After the first ascent, six other expeditions managed to climb the Pillar. None of the six used bottled oxygen.

In 1980, John Roskelley made the West Pillar’s second ascent and its first without O2. Although part of a lightweight team, Roskelley made it to the top alone.

”We had chosen to raise ourselves up to the standard of the mountain, not to pull the mountain down to our level with large teams of climbers and Sherpas,” Roskelley later wrote in the American Alpine Journal.

Jim States and John Roskelley pause on a ridge as they shuttle gear to higher elevations on Makalu. Photo: Chris Kopczynski

In 1988, Marc Batard made an impressive speed ascent on Makalu’s West Pillar. We will discuss this climb in more detail below, especially how long it actually took.

In 1990, Kitty Calhoun (with partner John Schutt) became the first woman to climb Makalu, via its most difficult route, the West Pillar. She was also the leader of the expedition.

Kitty Calhoun, one of America’s best female climbers. Photo: Kitty Calhoun

In 1991, Carles Valles and Manuel Badiola Otegui of Spain also succeeded, but Badiola died during the descent when he fell from 8,300m.

Also in 1991, Erhard Loretan and Jean Troillet of Switzerland managed to climb a variant of the West Pillar, accessing it at 6,700m from the West Face, about one-third the way up, which is why it is a variant. They did it lightweight style, and like all post-1971 summiters, did so without oxygen.

In 2004, four members of a Kazakh expedition managed to summit the West Pillar: Jay Sieger, Vladislav Terzyul, Maxut Zhumayev, and Vassily Pivtsov. Unfortunately, Sieger and Terzyul disappeared during the descent.

Marc Batard. Photo: Marc Batard

Marc Batard, 1988

Following a speed ascent of the West Pillar, Batard summited Makalu alone on April 27, 1988, without supplementary oxygen. Batard employed four Sherpas to help him equip the route from 6,000 to 7,750m with fixed ropes and two snow cave camps. On his ascent, only Ongel Sherpa went with him to 5,900m on April 26. Ongel then returned, and Batard continued alone. Ongel’s partial presence and the fixing team’s participation is why Batard’s climb is not considered a true solo ascent.

But Marc Batard’s West Pillar ascent is interesting in other ways, especially now that Karl Egloff and Nicolas Miranda have just claimed an FKT on Makalu. They emphasize that they beat both Marc Batard and Anatoli Boukreev’s records.

Makalu, West Pillar Route. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

Batard’s timing

Marc Batard left his Base Camp at 4,950m, at 2 pm on April 26, 1988. From there, he arrived at the Swiss-German Base Camp at 5,200m. This would have taken him 1.5 to 2 hours. Here, he remained for an hour.

From 5,200m, he progressed to 5,800m (accompanied by Ongel Sherpa). Here, he stopped again for one hour, from 6 to 7 pm.

He started alone from 5,800m at 7 pm. He then reached the summit of Makalu (8,463m) at 9:45 am the next morning, April 27.

This means that from 5,800m — a comparable starting altitude to Egloff and Miranda — Batard climbed to the summit in 14 hours 45 minutes. As we’ll see below, that’s faster than Egloff and Miranda for the same height gain.

From his Base Camp at 4,950m to the summit, Batard took a total of 19 hours 45 minutes. His was a more complete ascent in traditional terms. [Update: Batard later told ExplorersWeb that he climbed from BC to summit in 18 hours. It is possible that he is not counting the two one-hour breaks.]

Egloff and Miranda also relied on a route fixed by Sherpas, so that element is comparable to Batard in 1988, even if the routes are different. However, the 2022 climbers had other clients and Sherpas around them for psychological security, whereas Batard was almost entirely alone.

A climber pauses on the West Pillar. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

Egloff-Miranda’s time vs Batard’s

The normal route that Egloff and Miranda climbed some days ago is different from Batard’s route. However, it is the same as Anatoli Boukreev’s 1994 line.

The normal route is not comparable with the West Pillar route, which is technically more complicated but also more direct. The normal route is longer, with one final complicated section. The two routes really are apples and oranges.

After the French Couloir at 8,200m, the upper section of the east ridge leads to the summit of Makalu via the normal route. Photo: Animal de Ruta

If we still want to compare times, Egloff and Miranda started from their ABC at 5,700m and reached the summit by the normal route in 17 hours 18 minutes. Batard, meanwhile, climbed from 5,800m to the summit in 14 hours 45 minutes — considerably faster.

Where does it end? Photo: Karl Egloff

Batard later wrote that it took him 18 hours to climb, but he probably — and this is just a theory — considered 4,950m as the start of the climb, but didn’t count the two hours’ rest he took along the way.

He would also have been justifiably more tired than this week’s two sky-runners since he had already put in four hours of climbing from his own Base Camp to 5,800m — roughly their starting point.

The West Pillar, foreground. Photo: Mapio Net

To add to the confusion, certain sources state an incorrect time of day when Batard reached the summit. In The Himalayan Database, in the expedition description, a typing error says that he summited at 7:45 am. The rest of the HDB report, the AAC, and even Batard’s own book lists the summit time as 9:45 am.

Toward the summit of Makalu. Photo: Karl Egloff

Speed ascent vs timed ascent

As we’ve noted, it can be hard to compare some speed records and FKTs because of quite different starting points. On some mountains, such as the North Side of Everest, the ABC is a long way from the BC and therefore a much more logical starting point for an actual climbing time. Other speed climbs have chosen to start from the roadhead, meaning a lot of horizontal running before the actual climbing starts.

Finally, we should also point out that in the history of alpinism, a speed ascent is not the same as a timed ascent. Batard and Boukreev both intended to make quick ascents, but they did not time themselves precisely by chronometer like a modern speed ascent requires. The rapid ascent itself was more important than timing the entire route up and down, from a sky-runner’s point of view.

As the late, great David Lama once said: ”The chronometer is not part of a mountaineer’s equipment.”

A climber on the West Pillar of Makalu. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro