Last spring, self-professed “pensioners” John Dunn and Graeme Magor skied from south to north on Axel Heiberg Island in the Canadian High Arctic. Then they turned around and skied most of the way back. But that wasn’t the most unusual part of their 58-day, 835km journey along the world’s third-largest uninhabited island. [Full disclosure: Magor and I have partnered on a couple of previous expeditions.]

They could have chosen the obvious route along the sea ice, the so-called arctic highway. It would have been faster and easier. The sea ice on Axel Heiberg’s east coast is particularly flat and windpacked. Hauling a sled over that surface is almost effortless.

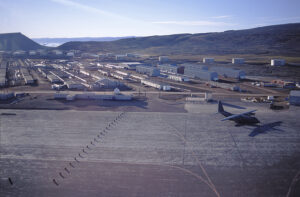

They began their overland route in late April, when snow still covered the land, left. By the end of June, right, the land was bare except for the ice caps, and open leads fissured the sea ice, forcing complex detours. Route line: John Dunn/Arcticlight

Instead, on the initial south-north leg, they picked a challenging overland route. The northern half of it had almost surely never been done before. In the High Arctic, where explorers’ artifacts take centuries to rot, it was an imaginative and tantalizing choice. What would they find? A box of supplies from some half-forgotten early expedition? A 1,000-year-old Paleoeskimo encampment? Another fossil forest, like the one accidentally discovered by a helicopter pilot in 1985?

Skiing across shallow snow cover. Photo: John Dunn/Arcticlight

Alpine style

Many of ExplorersWebs’ mountaineering readers praise alpine-style climbers and express impatience with the endless repetition of the same commercial routes up 8,000m peaks. The polar regions are less familiar to most of us. Just a fraction of the travelers go there compared to the Himalaya or Karakoram. Yet the polar regions often suffer from the same lack of imagination.

Right now, individuals or teams are skiing across parts of Antarctica, to the South Pole and sometimes beyond. They are paying huge bucks to do the same couple of routes as everyone else. Skiers do those same things in Antarctica every year, straining to make them sound different. Some, trying to set speed records along those well-worn paths, acknowledge that adventure has become sport.

A few months later, in late spring or summer 2023, the same will happen in Greenland: a variety of crossings, many of them near copies of one another.

Yet hundreds, even thousands of new routes are possible in the polar regions. Dunn and Magor’s so-called Double Axel was one of them. It was alpine style, not because they were unsupported — although they were — but because it was different, exploratory, driven by curiosity.

John Dunn, left, and Graeme Magor. Photo: John Dunn/Arcticlight

Trimming weight

They started the route on April 29 from the southern tip of Axel Heiberg Island, pulling two small sleds each. They had 56 days of dried food with them. Early on, to be cautious, they decided to extend their supplies to almost nine weeks by cutting their daily rations by 10 percent.

“Older folks don’t work as long each day,” explained Dunn. “Therefore, not so many calories needed…The smaller [lighter] sleds are another nod to age.”

The veterans chose their gear carefully to minimize weight. They only used 100ml of fuel per person-day. “The fuel efficiency of the WhisperLite stove and Primus heat exchanger pot was so good,” said Dunn. He also carried a 600gm sleeping bag and used his warm clothing to boost the rating. “It worked well, even at -25˚C,” he said.

A serious photographer, Dunn also carried a much lighter tripod than in the past. They also used a lighter rope for lowering sleds down slopes and brought ultralight packs for portaging and day hikes.

A hard slog through deep, soft snow early in the trip. Photo: John Dunn/Arcticlight

Lost a week

The first weeks were hardest, especially the 1,500m climb up the Strand Glacier with fully laden sleds. Soft snow made the climb even harder, and katabatic winds — common in that part of Axel Heiberg — coupled with violent storms gave them some weatherbound days.

“[It took] 11 days for 40km,” said Dunn. “We lost almost a week there.”

Tentbound during a gale. Quiz: Which direction is the wind coming from? Photo: John Dunn/Arcticlight

During that climb, they had to cover the same distance three times, double-hauling one pair of sleds, then returning for the second pair.

“I’d never hauled 60 days of food before,” said Dunn. “But we took our time, always hauled as a train, and slept like babies.”

Eventually, conditions improved and they began to thread their way through the inland valleys in the northern half of Axel Heiberg. The snow allowed their land traverse but it also buried any historic details. They didn’t see signs of past travelers, indigenous or European. A little more than halfway up the island, they cached two of the sleds and some of their remaining supplies, as planned, to shed weight. They would retrieve them on the way back.

Graeme Magor hauls through Bukken canyon, near the northern end of the island. Photo: John Dunn/Arcticlight

The return voyage

They reached Cape Stallworthy at the northern tip of Axel Heiberg on June 7, just a few days behind schedule. They turned around right away. By now, the snow was mostly gone from those interior valleys, and they had to stick mostly to the sea ice.

“The return from [Cape] Stallworthy — the ‘Double Axel’ thing — was definitely economically inspired,” said Dunn. “The trip would not have happened otherwise.”

The costliest part of the journey was the bush plane that they had to hire to get to uninhabited Axel Heiberg Island and back. So the farther down south they could ski, the less expensive the return charter would be.

For the same reason, the Quebec canoeists who covered almost the vertical length of Canada last year did not begin at the northern tip of Ellesmere Island but halfway down the island. The missing 600km cost them the right to claim a full Canada North to South expedition, but cutting their flight by two hours saved them $30,000.

Magor, an arctic history buff, did make one nice little discovery near the north end of Axel Heiberg. They passed the last verified campsite of Frederick Cook on his 1908 North Pole expedition — on the sea ice at Svartevoeg, or the Black Cliffs, right by a distinctive crack between two sections.

Frederick Cook’s 1908 camp at the Black Cliffs, near the northern tip of Axel Heiberg Island.

Magor carried the image that had appeared in Cook’s book Return From the Pole. He and Dunn noticed from the orientation of the cliffs that the historic photo had been printed backwards.

Note that the dogsleds in that image are oriented for southward travel (right to left) when Cook was going north at that point, Magor pointed out. “Why didn’t [anyone] ever notice that before?”

Spring becomes summer

They headed south at 25km a day and were hopeful of reaching the south end of Axel Heiberg Island in time. But it was now full summer in the High Arctic, and the melt — always dramatic because of the 24 hours of sunlight — overtook them.

“Sloshing around is not so bad,” said Dunn. But open-water leads forced time-consuming detours as they sought to work their way around the jigsaw of ice and water.

By late spring, snow has disappeared from the land, rivers are flowing, and sloshing is required. Photo: John Dunn/Arcticlight

Lining the sleds along the shore lead. The ice further out is still plenty thick, if you can get there. Photo: John Dunn/Arcticlight

It was too late for a plane to land on the sea ice, so they stopped at the last gravel delta where the tundra-tire-equipped plane could land. They stopped 200km short of a complete double traverse.

The veteran Dunn’s biggest surprise on the expedition? “How well the body still worked, and how well it survived all the hard work over so many days.”