Until 1921, Mount Eon was an unclimbed 3,310m peak in a remote part of the Canadian Rockies. That year, Dr. Winthrop Ellsworth Stone and his wife, Margaret, went to attempt the first ascent of this peak near the Alberta-British Columbia border. However, an accident soon turned the climb into a crisis. Winthrop fell to his death, and Margaret had to survive on the peak for a week.

By 1920, Mt. Eon remained one of the few major unclimbed summits in the area. That year, a party from the Alpine Club of Canada that included Dr. Arthur William Wakefield and Lennox H. Lindsay made an unsuccessful stab at it, according to the Alpine Journal.

Wakefield was an English physician, explorer, and mountaineer best known as one of the doctors on the 1922 British Mount Everest Expedition. He almost reached the North Col to provide medical support. Lindsay was a member of the Alpine Club of Canada.

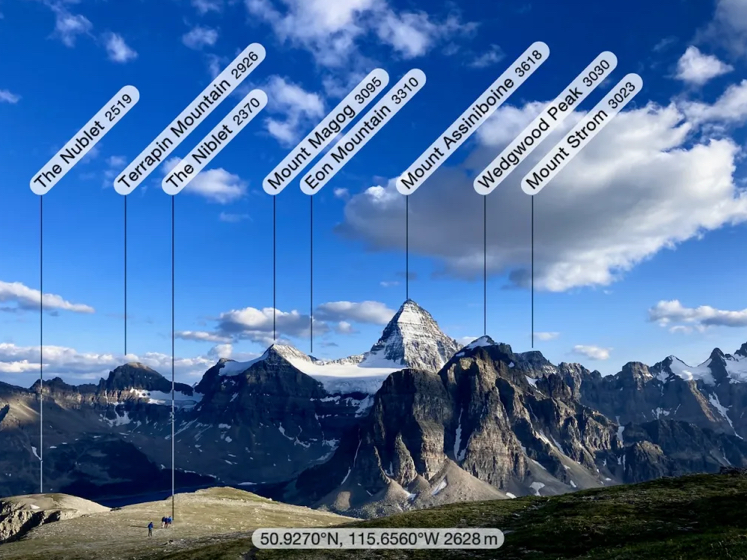

Eon Mountain lies just south of iconic Mount Assiniboine, often called the Matterhorn of the Canadian Rockies. Photo: Besthike.com

The climbing couple

In 1921, the Rockies were wild and far from towns. People went there to hike, to climb, and take a breather from everyday life. Winthrop Ellsworth Stone and his wife, Margaret, loved that world. Climbing brought them together, and they spent summers climbing in the American West and Canada.

W. E. Stone was born on June 12, 1862, in Chesterfield, New Hampshire. He studied chemistry, earning degrees in the United States and Germany (including a PhD from Gottingen). He became a professor at Purdue University in Indiana, and by 1900, he was the university president. Stone was serious about his work, but the mountains called him every year. He was a member of the Appalachian Mountain Club, the American Alpine Club, the Alpine Club of Canada, and others.

Stone’s first marriage ended in divorce in 1911. A year later, at the age of 50, he married Margaret Winter (later Margaret Stone). She shared his love of the outdoors and often climbed with him. They were a strong pair, used to long days. The couple had been active members of the Alpine Club of Canada for a decade. During this time, they achieved several first ascents, mostly in the Purcell Range in 1915 and 1916.

In 1921, the Alpine Club of Canada held its camp near Mount Assiniboine. At 59, Stone wanted one more big climb, so the couple decided to go without guides to climb Mt. Eon. Although Swiss guides were already common in the Rockies, climbing without them was also popular, though the risks were real on unknown rock.

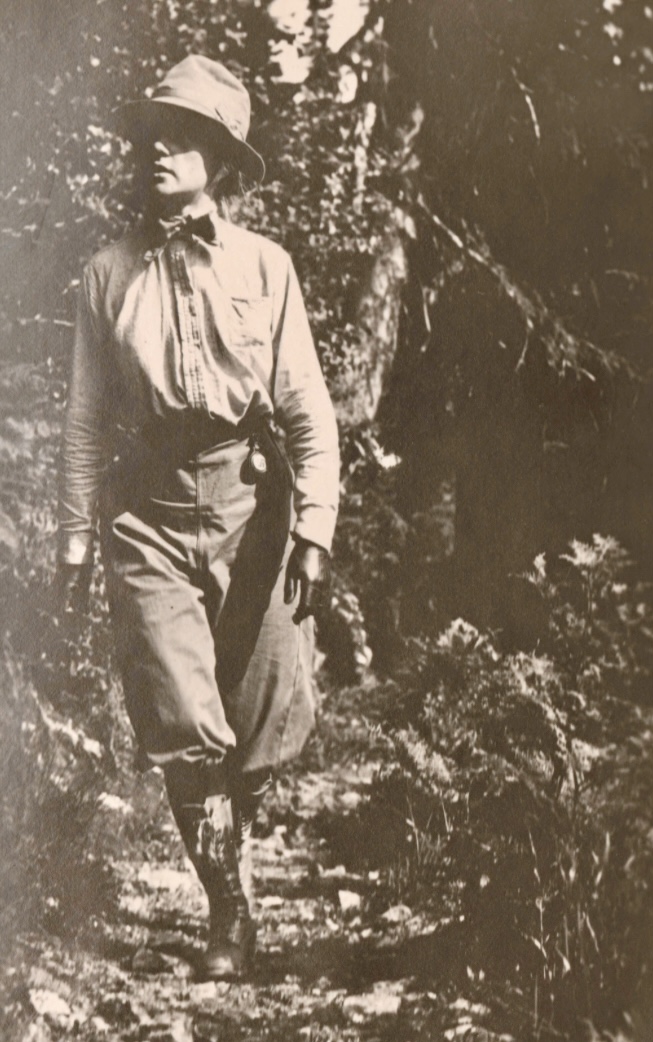

Margaret Stone. Photo: Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies

The first ascent of Mt. Eon

The Stones left the Assiniboine camp on July 15, 1921, crossed Wonder Pass, and hiked past Marvel Lake. They set up a small bivouac below Mt. Eon, where they spent two nights before starting the ascent on July 17. The weather was clear as they navigated a route via broad ledges, steep couloirs, the southeast arete, a snow band, and broken ledges. Eventually, they came to the final wide, steep, irregular chimney with unstable overhanging sides, according to the detailed route description in the Canadian Alpine Journal.

Late in the afternoon, at around 6 pm, they reached the base of the final chimney, about 12m from the top. Stone went ahead up the chimney, reached the summit, and called back that he could “see nothing higher,” according to the Alpine Journal and the Whyte Museum’s report. He became the first person to summit Mount Eon.

The fatal accident

But triumph turned to tragedy in a heartbeat. As Stone began his descent, he stepped onto a slab that looked solid but wasn’t. Before Margaret could even cry out, he was gone, tumbling 260m down the rock face in terrifying silence.

He held his ice axe but made no sound, according to later reports. Margaret watched him disappear into the void below. The successful ascent on a glorious day had turned to a nightmare. Margaret could not spot Stone after the fall and was completely alone near the top.

The Stones during a climb. Photo: Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies

A difficult survival

Alone on a narrow, sloping ledge, Margaret faced a nightmare that lasted seven days.

On July 18, she began descending, passing her husband’s body. By July 19, exhausted and without food, she reached a narrow ledge on the south face from which she could neither advance nor retreat. She was stuck. There was barely room to sit, exposed to the wind and cold. She wore only climbing clothes: a wool shirt, knickers, and boots.

Days passed, and survival was difficult. According to the Alpine Journal, she depended for water on a cushion of moss on the rocks. Enough moisture accumulated in the moss every three or four hours to provide a small drink. She scooped tiny holes in the stone to catch the drops and licked them slowly. She called out every day, hoping her voice would carry down the valleys.

Margaret stayed on that ledge for seven days (July 17–24), bruised, weak, and chilled by nights below freezing, though the south-facing sun warmed her during the day. She kept her watch wound to ration the water and mark time.

Marvel Lake. Photo: andrewswalks.co.uk

Worry grows, rescue starts

Back at the camp, people noticed that the Stones hadn’t returned by their planned July 18 date. Worry grew as initial checks on July 19–20 found no traces.

A message finally reached Banff on July 21, and the rescue that followed was a race against time. Legendary Swiss guide Rudolph Aemmer and Bill Peyto led the way. They and several volunteers reached the camp late on July 22 after a long, hard ride.

On July 24, they heard faint calls, spotted Margaret through glasses, rappelled down, and secured her. She was too weak to walk, so Aemmer carried her on his back for hours down to timberline, where Dr. Fred Bell fed her. They used an improvised stretcher on the steep parts, rafted across Marvel Lake, and moved her slowly to Banff, where she recovered remarkably well, at least physically.

Finding Stone’s body

Finding Stone took longer. His body was deep in the fall zone on a ledge. A second party, strengthened by Conrad Kain, Edward Feuz, A. H. MacCarthy, L. H. Lindsay, Rudolph Aemmer, and others, under A. O. Wheeler’s direction, returned on August 5 and recovered his body after two days under incessant falling rocks, according to the Alpine Journal and Canadian Alpine Journal. They transported the body back to Banff on horseback. Stone was eventually buried in Spring Vale Cemetery, Lafayette, Indiana.

News traveled fast. Papers across North America carried the story of the Purdue president who died on a first ascent and his wife, who survived alone for a week. At Purdue, people were shocked. The school named an acting president and searched for a new one. Stone’s name lives on in buildings and a college there.

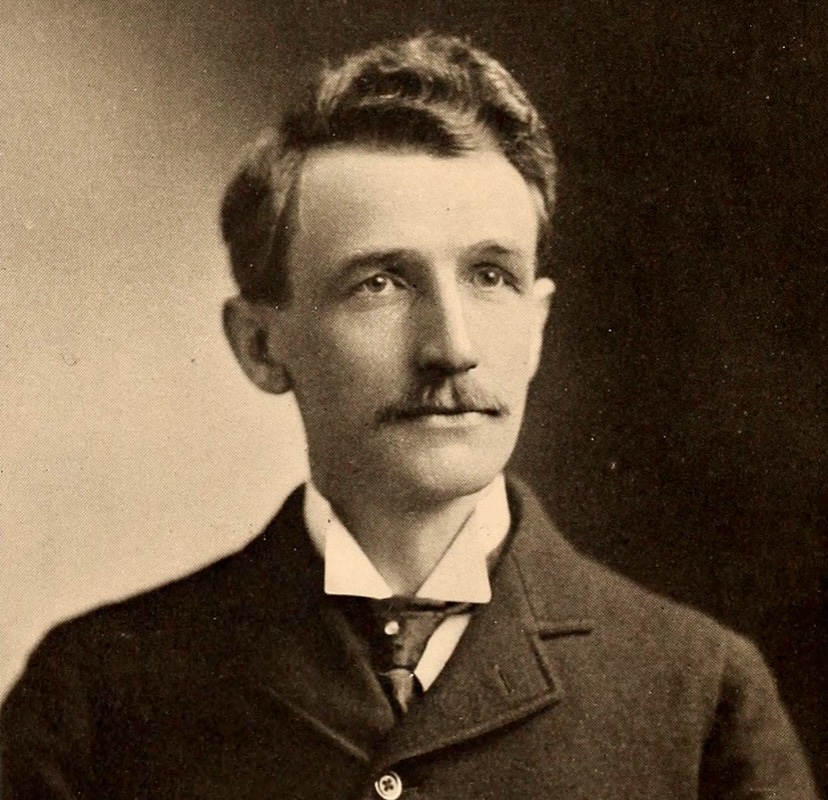

Winthrop Ellsworth Stone. Photo: Wikipedia

Margaret Stone recovered but stayed out of the public eye afterward. According to family documents cited in the Whyte Museum’s 2021 article, she never spoke about those days again and gave up mountaineering entirely. She moved to the East Coast of the United States, eventually settling in Florida, and passed away in 1969 at the age of 89. She was buried alongside her husband in Indiana.

Soon after the rescue, the guides built a memorial cairn on the summit, crowned with Dr. Stone’s ice axe, confirming he had reached the top before the fall.