Just when we thought that we had already covered the most outstanding expeditions of a remarkable year, we got a heads-up from an American alpinist about a “recent ascent done by a small team in Pakistan that I think is probably the best climb of the year so far!”

After reading the reports and speaking with the climbers, we can only agree.

The ascent of a difficult new route on 6,000m+ Aikache Chhok in Pakistan by James Price of the UK and George Ponsonby of Ireland is a true adventure on a 3,000m route of high commitment, involving an epic nine-day climb between October 13 and October 21.

We first heard of James Price in 2022 after his bold solo attempt to traverse the entire Batura Wall in the Karakoram. He did most of it before finally turning around with frostbitten toes. Despite the injuries, he returned on his own — five kilometers of ridge, a glacier, and 70km back to town. (Watch a documentary about the adventure here.) Meanwhile, George Ponsonby, who was on his first climb in Asia, provided great insight about the climb in an interview with ExplorersWeb.

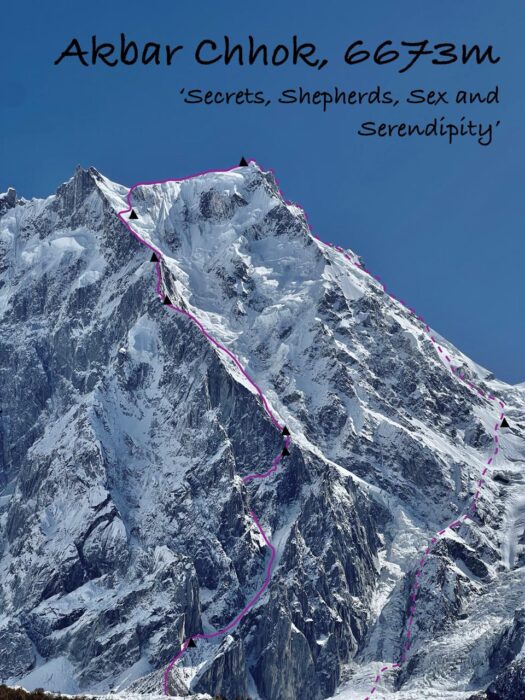

Route topo provided by the expedition team. They graded the route M7 AI5 A2+.

Brainstorming

Ponsonby and Price met as members of the UK’s Young Alpinists Group (YAG), a mentorship program founded by Tom Livingstone for experienced yet young alpinists of the UK and Ireland. Members spend three years participating in a series of progressive climbing events.

“We were in Scotland on a YAG trip last January, and everyone was asked to come up with an expedition idea for the summer or autumn,” Ponsonby told ExplorersWeb. “James and I spent about 15 minutes coming up with ideas and making a presentation. Mine was somewhere in Tajikistan, and James chose a valley he hadn’t yet been to in Pakistan…Neither of us thought that our ideas would be popular, as they were so unprepared and sparse on details, but somehow James’ got voted as the first choice and mine as the second. So we ended up going to Pakistan.”

Training while salmon fishing

“We prepared for the expedition as well as we could, which wasn’t well at all,” admitted Ponsonby.

He explained that Price injured his ankle tendon shortly before the trip, which caused him acute pain. “He brought a ski boot and had planned to climb in that to keep his ankle immobilized,” Ponsonby noted.

Meanwhile, Ponsonby spent the summer commercial salmon fishing in Alaska from 6 am to 11.30 pm every day.

“That meant no climbing and no uphill training since the end of June,” he said. “The job is really physical, and while I got a lot stronger working it, it’s not climbing muscle.”

Still, YAG coach Tom Horrocks of Adventure Fitness Consultants suggested some exercises to do, in addition to his exhausting job.

“Because of that, we weren’t planning on doing anything that crazy, but James’ ankle stopped giving him issues while we were in base camp (so no ski boot required), and I found myself fitter than I thought, so our ambitions just started to grow,” Ponsonby said.

No specific goal

The YAG group in Pakistan consisted of three climbing teams. The pair of Price and Ponsonby had no specific goal in mind.

“We couldn’t really find any photos, so we didn’t make any plans for any line ahead of time, just deciding to turn up and see what looked good.”

They wandered along two valleys, from Sani Pakush to the Batura Wall, looking for suitable objectives. In the end, they chose a peak right in front of their base camp tent.

A stunning base camp setting. photo: YAG Pakistan 2025

The climbers spotted a long ridge/buttress straight up the northwest face of a peak called Aikache Chhok in the Haachindar Massif. The peak had previously been climbed from its south ridge by a 1983 Italian team consisting of Enrico De Luca, Giorgio Malucci, and Gianpiero Di Federico.

“They climbed from the Shilinbar Glacier to the south,” Ponsonby told us. “[There have been] no recorded ascents since. The summit is also referred to as Sia Chhish from the Shilinbar side, Yain Hisq Sar from the Muchuar side, and Akbar Chhok from the Baltar side. Altitude reports vary from 6,300m to 7,040m.”

The two decided to try it via a new route from the north. As soon as a weather window opened, they took food for five days and fuel for seven, and left on October 13.

On the rocky buttress. Photo: Ponsonby/Price

The climb

“The first day of climbing, we started strong, making good progress up a main gully. Then [we continued] left into a side gully, before reaching about six pitches of mixed climbing up to M5/M6 to connect small snowfields further and further up a face to try and reach the ridgeline,” Ponsonby wrote in the expedition report. “The day ended three pitches below the ridgeline. Both of us were happy about the progress and naively thinking our five-day timeline seemed pretty reasonable.”

“Day two then kicked us right up the hole,” Ponsonby recalled. “It took all day to climb just three pitches.”

The mixed terrain required some aid climbing (around M7/A2+). The day included a slightly overhanging crack on rock that became looser and looser. Price overcame it with some aid climbing. Then Ponsonby led the last part on varied terrain to the ridge.

James Price at the overhanging rocky outcrop. Photo: George Ponsonby

The climbers noted that part of their north-side route was cold and shady. “The ambiance had become a little too ‘Grandes Jorasses-ey’ for our liking,” he said.

On the third day, they gained altitude on mixed terrain up the side of the ridge, as the ridge itself was only suitable for rock shoes, not with the alpine boots the climbers had with them. Finally, they reached a glacier with some snow ledges, and then back to the ridge in mixed terrain. That night, they bivvied under what they called the “second rock step.”

Difficult mixed terrain. Photo: Ponsonby/Price

The hardest day

To avoid the rock step, the climbers rappelled down and traversed toward some ice ramps, but this turned out to be a dead end. By the time they realized they were going nowhere, the light was fading, and they had to stop.

“That night, to make ourselves feel better, we made what we thought was custard, but ended up being some inedible, mango-tasting, plastic-like substance that had to be thrown away.”

“That day was the day the route really started to feel hard for us and was the closest we came to turning around,” Ponsonby told ExplorersWeb. “However, we both felt it was worth one more try, though with an optimized strategy: On the following morning, I got a light leader bag and climbed as fast as I could through the ice.”

That fifth day was an endless climb on ice, eight pitches up to AI5, most of them 60m rope stretchers on rock-hard glacial ice, and a vertical snow pitch to exit back to the ridge in the dark. Here’s Ponsonby’s account of the day.

Climbing on hard Ice. Photo: Ponsonby/Price

My nerves got pretty shot by the end. We broke two ice screws and I chipped one of my picks from the rock-solid ice. When I finally topped out onto the ridge above the second rock band, I let out a scream of relief, took a couple of steps and fell into the bergschrund of the serac below us. I was so tired I just sat down and belayed from there, using my body weight as an anchor. After all that effort, we didn’t think about retreating again. While possible (both of us had a retreat route in the back of our minds), it would have been two days minimum to get off.

The ‘Karakorum flop’

That night, they prayed for an easier sixth day. Instead, when they looked up after passing a small hump, they saw nearly 1,000m of black ice up the ridge, with some chossy rock steps thrown in. With battered feet from the previous day, the pair perfected a technique they dubbed the “Karakorum flop.”

To execute a good flop, you climb as far as you can up slabby black ice from your last ice screw, ideally while simul-climbing. When you can’t take the pain in your toes and calves any more, you drive in the ice axe and clip straight into it. Then, relax every muscle in your body.

If the bag starts to tip you backward, just let it, don’t fight anything. After a minute of complete relaxation, only then do you start to even think about putting in a screw. Clip the screw, then rinse and repeat the entire procedure until you’re out of screws.

Added Ponsonby: “It was James’ turn to lead all day the next day as I was a bit mentally done for, and he did an amazing job.”

After dark, they found a bivy spot in a crevasse at 6,150m.

Endless days of ice climbing took a toll on the climbers’ feet and energy. Photo: Ponsonby/Price

Elusive summit

“Day seven continued up the glacial face with more simul-climbing on snow, an overhanging ice step, and one and a half pitches of steep black ice to the ridge between the mini-summit and the main summit,” Ponsonby wrote.

While on the summit ridge in deep snow, the sun finally appeared for a few minutes before fresh storm clouds enveloped the climbers in a whiteout.

What followed was mental torture. The climbers slowly plunged through deep snow to the place marked as the summit on the map. It was not: Two hours later, they were still going up. Eventually, the mist cleared up and they saw a corniced summit still two pitches beyond them.

The summit of Aikache Chhok. Photo: Ponsonby/Price

“Completely unwilling to do any more climbing and with terrible visibility, we threw up the bivy tent right below it and jumped inside it to wait out the bad weather overnight, recalled Ponsonby. “We shivered the night away, barely able to eat and just focused on keeping all our extremities as warm as we could.”

Still, with his last grams of energy before pitching the bivy tent, Price fixed a pitch up the cornice to ease the way on the following morning.

On day eight, the climbers shared their last remaining energy bar for breakfast. In clear weather, they climbed the cornice, summited, and immediately focused on how to get off the mountain. They were in such a hurry that they didn’t check the final altitude. “We recorded 6,663m on a Garmin one pitch below the summit,” said Ponsonby.

Two days down

The climbers had not been able to see the descent route while they were in base camp or scouting the mountain due to persistent clouds, so they had to risk a descent with no information, on unknown terrain, and with poor visibility.

“However, tough descents are where James really starts to shine,” Ponsonby wrote.

They started to rappel, first off on rock and then off endless V-threads (abalakovs), with complex glacial crossings, rapping over seracs and rock sections, until they found a bivy spot at around 5,000m at sunset. There, they enjoyed the “massively comforting” sight of headlamps shining up at them from base camp.

The descent continued on the ninth day down a large rock rib. They passed quickly under some threatening seracs and finally reached the base of the mountain.

Rappelling down. Photo: Ponsonby/Price

Half-brother George

The climbers returned to base camp with no frostbite and in good health, yet much slimmer.

“I entered Pakistan weighing around 180lbs, and when we got back to Aliabad, the scales showed around 160lbs,” Ponsonby told ExplorersWeb. “I went from being called ‘younger brother George’ (guess James gives off an older vibe) to ‘half-brother George’ because I apparently looked a fair bit smaller.”

The shepherds

There were shepherds and hunters in the area near their base camp. “[One of them,] Akbar, lent us a hut to use, which was very generous, and all the shepherds there showed us amazing hospitality,” Ponsonby said.

It was his first climb in Asia, and he couldn’t talk enough about the experience of meeting the locals who invited the young foreigners into their huts for chai and food, who would sell them milk and butter each morning, and who were “as curious about our lives as we were about theirs!”

He added: “When we were climbing, apparently there were people looking at us through binoculars every day, checking our progress, and at night there would often be a chorus of head torches flashing up at us when we flashed them. It made the mountain feel less committing, especially as we got higher.”

Ponsonby and Price with local shepherds. Photo: YAG Pakistan 2025

They named their route Secrets, Shepherds, Sex and Serendipity. Asked about the meaning, Ponsonby said: “It’s just the name of some silly Bollywood-style screenplay we spent far too long creating while waiting around base camp during bad weather days. It just kind of stuck.”

One of 2025’s best?

When we mentioned to Ponsonby that some people thought their climb was among the best of the year, Ponsonby reacted humbly.

“It’s all relative,” he said. “Someone better than we are might come along and realize it’s quite easy. Plus, I’d always be cautious to make statements like that, as there’s almost always some unknown person who’s done something more impressive and hasn’t told anyone.

“Also, conditions always play a part. We’d have had a totally different experience in a different year with more or less snow, different ice, and neve conditions, different passages opening up through the tricky bits, different gear making the aid sections easier, etc.”

Traversing over mixed terrain. Photo: Ponsonby/Price

Yet both are extremely proud of their achievement.

“I can’t speak for James, but nothing I’ve done has come close to overall difficulty/effort,” Ponsonby said.

At least now he knows he’s capable of spending nine days on an alpine-style route. With Ponsonby only 29 and Price 28, there’s plenty of time for them to do more.

Editor’s note: At first we (and the climbers) reported it as a first ascent of a new peak in the massif, but Ponsonby later told us that they now realize that it was a new route on the same Aikache Chhok the Italians had first climbed back in 1983. We have since changed the story to reflect this new information.