Tyler Andrews had a lot on his mind when he began his second attempt this season to make the fastest-ever Everest ascent without oxygen. In addition to the climb ahead of him, a recent avalanche had occurred on the Lhotse Face, injuring several people from another expedition. He’d had a close call in the Khumbu Icefall himself on his first attempt, when a bridge gave way. Nevertheless, he kept going to 8,000m and a little beyond, until it became obvious that he was simply not going to break any record.

Tyler Andrews, 35, spoke openly with ExplorersWeb about the burden of climbing in such dangerous conditions, the frustration of defeat, and his hunger to return.

Harder than expected

“On the first trip up, we were basically flying blind,” Andrews explained. “We just knew there was a lot of snow, but we never imagined how much. We also knew that an avalanche on the Lhotse Face had trapped several members of Bargiel’s team. I couldn’t help worrying and checking the snow all the time, fearing the whole face was going to slide on top of me. That definitely made me lose time, and I didn’t have my head fully into the challenge. I soon understood it was time to call it quits and try again another day.”

Instagram Story shared by Chris Fisher as Andrews left Everest Base Camp last week. Photo: Chris Fisher

“On the second attempt,” said Andrews, “we had more realistic expectations. I had the trip mapped in my head, and I was sure it was feasible.”

Yet on that September 25 attempt, Andrews himself felt the shock wave of an avalanche after just 20 minutes.

“It was nothing serious, just some dust from an avalanche from Nuptse, but not the best way to start,” Andrews said.

He noted that the Icefall was more unstable than it had been last spring. However, he continued on, feeling strong and confident that he had time to summit within the planned 20 hours.

His pace up the Lhotse Face was good, but he started to slow down as fresh snow piled up near the South Col.

Defeat at Camp 4

Two Nepalese climbers, Lakpa Sherpa and Phurbu Sherpa, were waiting for him at Camp 4. It was arranged that they would start toward the summit before Andrews arrived in order to break trail for him.

“They are strong, reliable climbers, so when I saw they turned around shortly after they started, it was a bad sign,” Andrews recalls.

When Andrews reached Camp 4, the Sherpas had returned and were feeling “pretty much defeated,” he said.

“Andrzej [Bargiel]’s team included 12 Sherpas working in shifts as he went to the summit, breaking trail and taking turns to rest,” Andrews explained. “It was a lot of manpower, and yet it took them over 16 hours to get to the summit.”

Andrews thought they would find a somewhat packed trail from the Bargiel crew, but more snow had fallen or blown over the trail, and most of the ropes were buried.

“I considered taking a rest at Camp 4 and then proceeding to the summit, but that would have taken 18-20 hours, which made no sense for a speed record attempt.”

Andrews’ highest point reached on September 26 was from 8,000m to 8,050m, he estimates.

A wider perspective of the only photo Tyler Andrews took at the South Col. The summit section looms in the background. Photo: Asian Trekking Sherpa team

New variation route

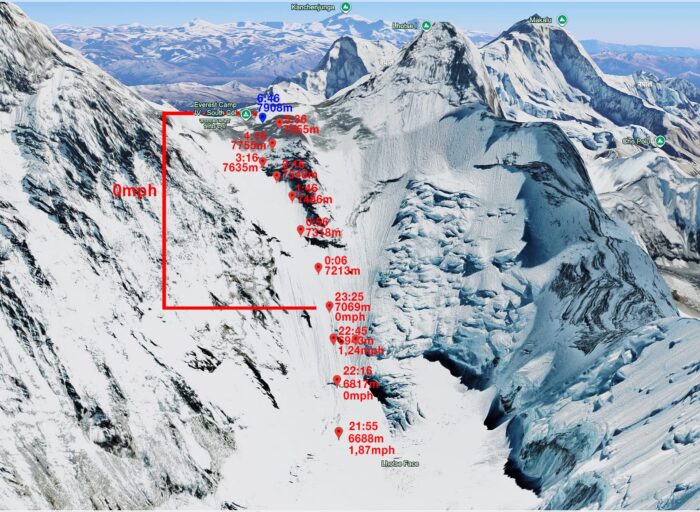

Andrews explained that everyone in the two teams on the mountain this fall took a different route than normal toward Camp 4, in order to avoid the avalanche risk on the Lhotse Face.

“The rope fixers saw several unstable snow slabs when they were heading for the standard Camp 3, and had to deviate to the left,” he said. “Later on, we all followed that variation route, where the fixed ropes were. As far as I know, no one went to the right side of the Geneva Spur.”

Andrews noted that this new variation was shorter and faster but also steeper.

Andrews’ route from Camp 2 to the South Col of Everest, based on the coordinates registered by his tracker. Topo compiled by @alpymon

Tyler Andrews climbed on his own, carrying his own stuff, but he was not alone on the route. In addition to the two Nepalese at Camp 4, the expedition had another small crew at Camp 2. “On the way up, I popped in there and got some water from the cook.”

Avalanche

Even before heading to Base Camp for his first attempt, Andrews heard over the radio that a big avalanche on the Lhotse Face had injured a number of people on the Bargiel team. Andrews knew that the risk on the Lhotse Face would be much higher in fall, post-monsoon, but when an actual avalanche occurred just days before his own initial attempt, he admitted that it stressed him out.

“The big avalanche took place 7-10 days before my first trip up, but there was still a huge pile of debris at the bottom of the face,” he said.

The first part of the Lhotse Face was not reassuring.

“There were wind slabs on top of powder snow, and some pieces were falling off, which was quite worrying,” Andrews said.

Nevertheless, he kept going, encouraged from Base Camp by Chris Fisher, a seasoned Colorado skier. He told himself that people had been going up and down that section every day since the big avalanche. Luckily, higher up, the snow conditions changed from slabby to deep powder snow, “which was annoying but safer.”

Andzej Bargiel progresses up the Lhotse Face during his 2022 attempt. Photo: Bartek Bargiel

Silence about the avalanche

Although Andrews was not on Everest at the time, he was informed that “several” people had been injured in the avalanche, presumably members of Bargiel’s expedition — the only other group on the mountain. There has been no official report about the accident, the names of the injured, or their present condition. We have requested more information from Andrzej Bargiel and his team, as well as details of his impressive ski descent.

Note that there was no direct communication between the only two expeditions on the mountain. They had separate camps, and Andrews admits he never had a chance to speak to anyone from the other team. However, the two Nepalese expedition leaders, Dawa Steven Sherpa of Asian Trekking (who outfitted Andrews) and Chhang Dawa Sherpa of Seven Summit Treks (who coordinated the local staff on Bargiel’s expedition), were in contact. The Nepalese, therefore, shared some information about snow conditions when Andrzej Bargiel summited and skied down.

Tiny figures of climbers and porters up the Lhotse Face, and the tents in Camp 4. Photo: Jon Gupta

Keep showing up

Despite the immense effort of launching two summit pushes on Everest within a week in difficult snow conditions, and a total of five attempts in five months to run up Everest without supplementary oxygen, Andrews says he had no realistic chance to summit in the 20 hours that would give him the mountain’s FKT. He admitted to us that he is frustrated, as he believes he has done everything possible.

You put in so much freaking work, and then it doesn’t work for whatever reason… and, you know, this was one of those where I really felt ready, I felt like my body had responded really well to the training…[and] on that last summit day. And then you get up there and, you know, if there’s two meters of snow to push through, it’s just not going to happen.

In marathon running, we say, ‘Keep showing up,’ meaning that if you just get fit and you get to the start line of every race, eventually you’re going to have a really good day, and your competitors are not going to have their best day, and you’re going to win. It’s maybe even more so in mountaineering, where there’s more outside your control than in a race…That’s the optimist in me.

File image of Tyler Andrews. Photo: Tyler Andrews

Andrews wonders if he could have done anything differently. He has even considered that his FKT might not be feasible, at least from the Nepal side.

“[However,] I’m proud of how I prepared, I’m proud of how I handled the events, especially the crevasse incident in the Icefall, and just being up there solo. The mountain just didn’t cooperate.”

To be continued?

Andrews won’t try again this fall, but what about down the road?

He says he’s still pumped to do it, but “I need to make up my mind about whether this is the kind of project that I want to just keep showing up for.”

Andrews pauses, then points out that this was Andrzej Bargiel’s third attempt to ski down Everest. “You know, maybe the third time will be the charm for me as well.”

File image of Tyler Andrews in the Himalaya. Photo: Tyler Andrews