Unicorns have a deeply rooted association with purity, young women, and nobility. Their association with Vikings, poison, and white powder of unknown origin is, in the modern day, perhaps less recognized. Nevertheless for the people of medieval and early modern Europe, the mythical horned horse was connected to all of the above. The unicorn was real, and so was unicorn medicine.

Some of the most famous art of medieval Europe features unicorns. To the people who created this tapestry, the unicorn was real, and they could eat it for power. Photo: The Unicorn in Captivity/MET

Good for what ails you

The first Western accounts of an equine, single-horned animal come from ancient Greek explorers in India. The unicorn appears in the works of Aristotle, Pliny the Elder, and more. The Hebrew word re’em, describing an unknown horned animal, was translated as “unicorn” in the 4th century Latin Vulgate, which became the official Bible of Roman Catholicism. Medieval people then cited the Bible as proof of the unicorn’s existence, in a neat bit of circular logic.

The unicorn was not merely a supposedly real creature but a potent symbol and substance. In popular Christian allegory, it came to symbolize Christ’s purity, humility, and oneness with God. The spiritual purity of the unicorn became a physical purity, and then the ability to purify.

Women were often painted with unicorns to symbolize their chastity. Photo: The Maiden and the Unicorn by Domenichino, Palazzo Farnese

The unicorn could heal wounds, cure disease, counteract poison, and purify water. Hildegard von Bingen, 12th-century abbess and mystic, wrote that “there is no leprosy, of any kind that will not be cured if you often anoint it with [an ointment made with unicorn liver].” If you wear a belt and shoes of unicorn skin, she went on, “you will always have healthy feet, legs, and loins.”

But the horn was where the unicorn’s power most resided, something attested in the earliest Western accounts of the creature. Drinking glasses made with its horn could counteract poison. The ground-up horn was the active ingredient in ointments, salves, and tinctures.

This tapestry, showing a unicorn purifying a fountain, is part of a famous series of seven. ‘Hunt of the Unicorn’ also shows the popular belief that a virgin woman could lure unicorns to her, for hunters to catch. Photo: The MET

Ten times its weight in gold

Henry VIII’s royal pharmacopoeia contained a recipe for an ointment containing ground unicorn horn, alongside red coral, white lead, oyster shell, and rose oil. It does not say what this ointment was used for. I can’t imagine it being effective against much of anything. But it was expensive.

Unicorn was medicine for only the wealthy. At the height of its popularity, powdered horn cost over ten times its weight in gold, while whole horns were even more valuable. Lorenzo de Medici’s horn, for instance, was worth 6,000 gold florins.

Ivan IV, aka The Terrible, paid 70,000 marks for a jewel-encrusted unicorn horn staff to a Welshman who claimed to be a wizard. He prized this object so much and believed in its healing abilities that he had it brought to him on his deathbed.

Unicorn was the perfect gift for the sovereign who had everything. In 807, Harun al-Rashid, Caliph of Baghdad, gave a nearly three-meter-long horn to Charlemagne. Pope Clement VII gifted a horn in a silver stand to the French King Francis I, and Venice gave one to Ottoman emperor Suleiman the Magnificent. Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I divided his vast treasure among his sons, except for the two most valuable objects: a unicorn horn and the (alleged) Holy Grail.

Horns were both displays of wealth and protection against the assassination all powerful people fear. The Spanish Grand Inquisitor Torquemada, for instance, refused to dine without his unicorn horn on the table. Mary Queen of Scots used unicorn horn powder to test her food for poison while she was imprisoned. Sadly for her, unicorn horn had no power to prevent beheading.

Ferdinand I’s ‘unicorn horn.’ Photo: Naturhistorisches Museum

The many horns of Elizabeth I

Appropriately for the “Virgin Queen,” Queen Elizabeth I owned several unicorn horns. Walter Raleigh’s half-brother, Humphrey Gilbert, gave the queen a jewel-encrusted horn worth £10,000, something like £10 million today. In 1577, Martin Frobisher gave her another unicorn horn, of a more marine origin.

Frobisher had just returned from an Arctic expedition. One day on Baffin Island, he had discovered the corpse of a massive, nearly four-meter-long fish similar to a porpoise. Emerging from the snout was a spiraling horn nearly two meters long. In his diary, Frobisher wrote that it “may truly be thought to be the sea-unicorn.”

Some of his sailors had apparently tested the magical powers of the horn by dropping spiders into it. Frobisher did not witness this strange experiment, but was told by his men that the spiders had died, somehow proving that the horn was magical.

Robert Dudley, one of Elizabeth’s favorites, is rumored to have stolen the tip of the unicorn horn belonging to Oxford College. Herman Melville’s claim in Moby Dick (Chapter 32) that he gave this to the Queen is, however, merely an off-color pun.

Elizabeth also had a goblet made of gold and unicorn horn, which she drank from, believing it would purify the contents. This cup was passed down to James I as part of the crown jewels. Frobisher’s horn was bejeweled and became known as the Horn of Windsor, while Gilbert’s likely became the silver-coated Tower Horn kept in the Tower of London.

Both of these items were lost or stolen during the English Civil War. During the reformation period, King Charles II received a replacement horn, but what happened to it is, likewise, unclear.

A 17th-century ‘unicorn-horn’ goblet. Photo: Kunsthistorisches Museum

The sea-unicorn

By this point, you’re probably wondering, given the fact that unicorns are not real, where all these goddamn horns are coming from. Well, as suggested by Frobisher’s sea-unicorn, they were coming from narwhals.

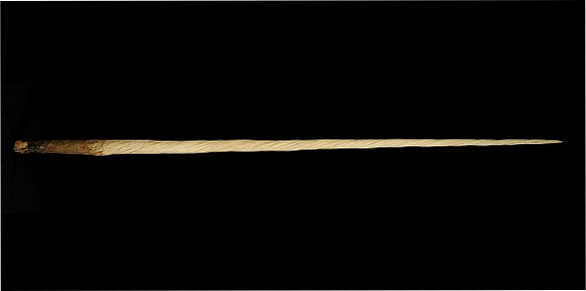

The narwhal is a small toothed whale that lives in Arctic waters. They grow up to three meters long, not counting their horn, which is another three meters or so. Actually, it isn’t a horn at all but a tooth, specifically the upper left canine. Most males grow tusks, occasionally even two tusks, while only a little over one in seven females do.

A small narwhal tusk. Photo: Facebook

The tusk may allow the whale to sense salinity and water temperature, but this is probably not its main purpose. If it was, we’d expect all of them to grow tusks, not just most males and a few females. It may be a result of sexual selection, with females preferring males with large tusks, or an adaptation for male narwhals to battle with in the fight for territory and mates.

Narwhals don’t usually leave the Arctic, but occasionally confusion, predation, or food scarcity push them out of their native range. In 1588, for example, a very lucky Welsh woman found a horn washed up on the beach and became fabulously wealthy. In 1949, a living pair of narwhals swam into British rivers to the surprise of all, and the consternation of the narwhals, who quickly found themselves in a museum collection.

But these incidents are so rare that they cannot account for the majority of the “unicorn horns” of medieval and early modern Europe.

Narwhal. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Vikings and corpse whales

While most of the world was ignorant of the narwhal, the people who lived around and traveled regularly in the Arctic were familiar with them.

It is the Old Norse language, through the Dutch, which gives us the word “narwhal.” Their word was náhvalr, from nár, meaning “corpse,” and hvalr, or “whale.” It was called the corpse whale, linguists theorize, because its round, mottled form bobbing on the waves resembled the pale and bloated corpse of a drowned sailor.

At the end of the 10th century, Norse sailors reached Greenland and set up a settlement there. The Norse Vikings (Viking is more a job, something like sailor/marauder/merchant, than a people group) had vast trade networks across Eurasia and North Africa.

Walrus ivory was a valuable trade good for the Greenland Norse, who did a brisk trade in the stuff. By the 10th century, walrus ivory from Greenland and Iceland was turning up in Islamic and Chinese markets. Along with the walrus came the much rarer and more valuable narwhal tooth ivory. The unicorn horns sold to the kings and popes of Europe were the same narwhal tooth that the Vikings sold as fine whalebone in the east.

The problem is that we have no record of the Greenland Norse hunting narwhal. In fact, they wrote that this animal’s flesh was inedible. (Clearly, it is an acquired taste, since Inuit love the stuff, particularly the skin and blubber, called muktuk.)

The Norse built this church around 1300, in the settlement of Hvalsey in southern Greenland. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Secret trade route?

In Old Norse, narwhals were inedible corpse whales. But people who lived with and hunted live narwhals gave them different names, with different regional dialects of Inuktitut referring to their black-and-white spots (Allanguaq), or tusks (tuugaalik). In fact, it was likely various Inuit groups, trading with Norse voyagers, who actually provided the priceless unicorn horns for royal treasuries.

A 2024 study used genetic analysis to source walrus ivory artifacts to specific hunting grounds. This study found that as time went on, the Norse had to go further and further into the Arctic and toward Canada, as they killed off all the closer walruses. As they pushed deeper into the Canadian High Arctic, they met the Thule — the few dozen people who lived in Northwest Greenland — more and more often and started increasingly exchanging goods and cultural knowledge.

By the High Middle Ages, Norse traders were making regular trips from Iceland to Greenland, where they traded with both the Greenland Norse and the Thule. And some of what they traded, scholars believe, were narwhal horns.

This 12th-century gaming piece was carved in Cologne out of walrus ivory from the Arctic. Photo: Victoria and Albert Museum

Unicorn trade dies, skepticism is born

The Greenland Norse abandoned their Western settlements around 1350. The Eastern Settlements were empty by the 1540s. As narwhal horn and walrus ivory imports slowed, however, elephant ivory imports increased. The colonial age was kicking off in earnest, which was bad news for most of the people and animals on Earth but cool for walruses. The elite of Europe began to get their ivory from Asia and Africa instead of from the north.

Besides, unicorn horns were beginning to seem a little last century, a little gauche. While Elizabeth I’s horn was worth £10,000, Charles I’s was only valued at £500. Maybe it was a smaller or perhaps uglier horn, but still the value of such objects had plummeted. In fact, some intellectual types were suggesting that unicorns weren’t real at all.

Emerging — not for the first time — to challenge a strange medical practice, Ambrose Pare published a discourse on unicorns in 1582. The royal doctor to four French kings, Pare was not afraid to challenge old medical wisdoms in favor of new evidence. He was skeptical of medicinal cannibalism and debunked the myth that gunpowder was poisonous in wounds.

Regarding unicorns, he argued that 1) they didn’t exist and that therefore 2) their horns did not have healing properties. No one, he argued, had presented reliable evidence of unicorns, and the descriptions of them varied wildly. In his many decades of practice, he had never seen unicorn horn or powder demonstrate healing or purifying properties.

Pare faced considerable criticism, with one anonymous troll calling him “Lucifer” and arguing that the unicorn cure was well established. Pare countered that long use was not evidence for efficacy, but many were not convinced.

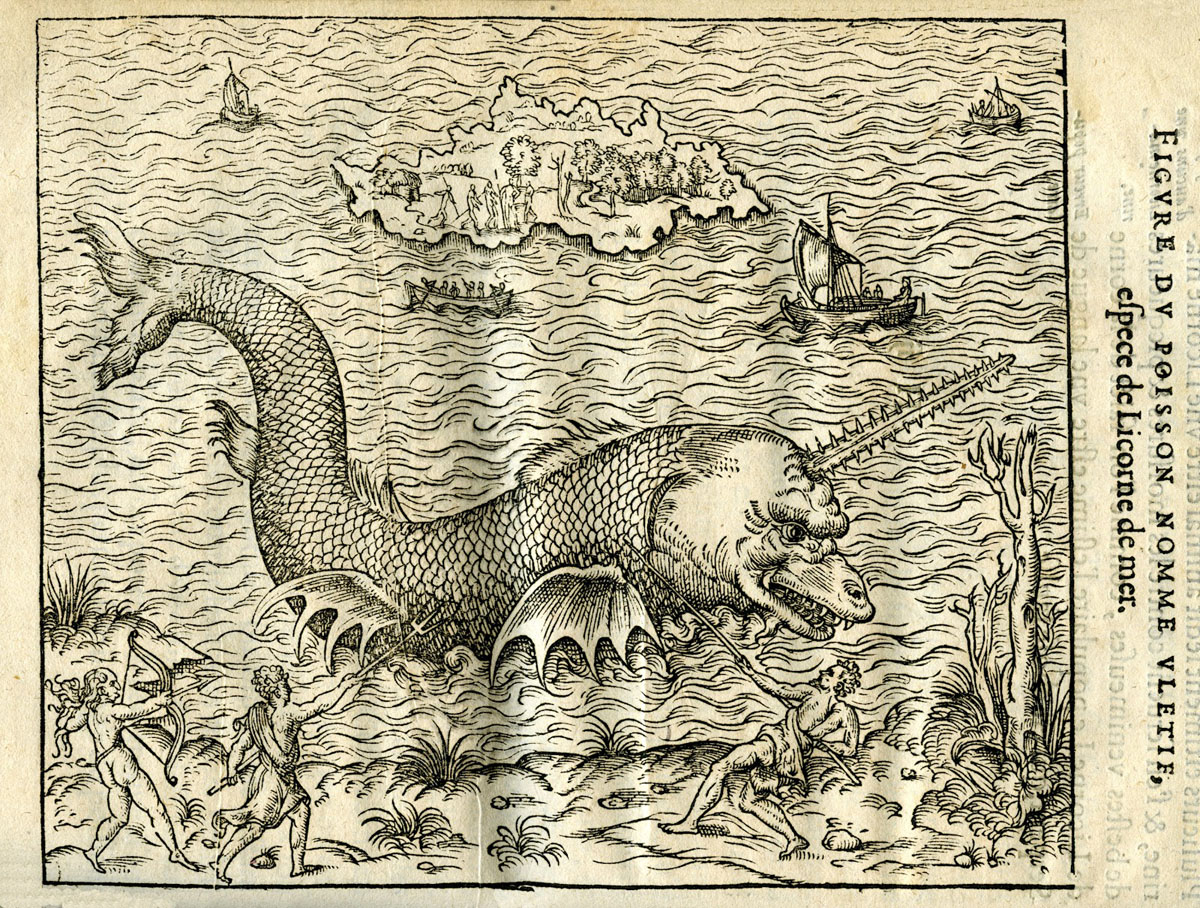

Pare also wrote that there were fish who had single, long horns, including this woodcut in his 1582 work.

The end of unicorn medicine

Apothecaries still used the unicorn as their logo, but Pare’s side was starting to get louder and more numerous. During the 17th century, European intellectuals had more information than ever before about the world beyond their backyard. At the same time, there was an emerging interest in scientifically cataloguing the natural world.

With these two trends, it was inevitable that the mythical unicorn would transform into two real, but very different, animals. The unicorn or monoceros of the land was the rhinoceros. When Marco Polo saw a “unicorn,” which he described as disappointingly ugly, that was probably a rhino.

As for the narwhal, it was delineated by a Danish physician who had the fantastic name of “Ole Worm.” Ole Worm got his hands on a narwhal skull and used it to demonstrate that unicorn horn was actually the tooth of an Arctic marine animal. Other treatises, like Paul Ludwig Sachs’ 1676 Monocerologia, further argued the narwhal/unicorn identification.

People are conservative and were slow to accept this blow to whimsy in medical annals. One 1694 compendium of medicine insisted that unicorn was still used “to resist all manner of poisons, and cure the plague, with all sorts of malignant fevers, the biting of serpents, mad dogs, et cetera.”

Into the late 18th century, some apothecaries still sold fossilized unicorn to treat the plague. Honestly, in the days before penicillin, it wasn’t the worst thing you could try.