Tenerife, an island off the coast of Morocco, was not on my radar before 2023, when I found myself teaching English there for seven months. After three flights, four airports, and 23 hours of flight time, I made it to the largest of the Canary Islands in one piece. As I settled in, I began to research the island’s history and soon discovered the fascinating history of the Guanches.

Who were they?

My home base on Tenerife was La Orotava, a village on the slopes of Spain’s highest peak, El Teide. The volcano’s summit greeted me every time I stepped outside my door, and its presence was a quintessential part of day-to-day life on the island. Using my somewhat okay Spanish, I asked the locals about the volcano and its history. One word kept popping up: Guanches.

The Guanches were the island’s original inhabitants. They were described as blonde, tall, strong, light-skinned, and speaking an unknown language. Anthropologists are unsure how they arrived on the island and how their civilization developed in isolation. Evidence suggests that the Guanches were not a seafaring people. Excavations have found no evidence of boats, rafts, or sails. When the Spanish invaded, it seemed that these mysterious people were always just…there.

The lack of information has prompted a few theories, including that they were former Roman prisoners or a Berber sub-group. DNA analysis has confirmed a North African origin.

Though we know little about them, the legacy of the Guanches can be found in every nook and cranny on the island, from the top of El Teide to the sweeping coastline. Let’s start at the top.

Statue of one of the Guanche kings in Candelaria, Tenerife. Photo: Kristine De Abreu

El Teide

Originally, the Guanches called the volcano Echeyde, but over time, it evolved into Teide. Linguists think it might mean “mountain of evil” or “hell,” and the locals feared it. In their mythology, the volcano was home to a demon called Guayota, the great adversary of the sky god Achamán.

To prevent this malevolent being — who usually appeared in the form of a vicious black dog — from causing havoc, the Guanches climbed El Teide during eruptions to light bonfires and scare him away. Achamán eventually defeated Guayota and imprisoned him inside the volcano. Since this battle, the Guanches used El Teide as a place of worship, leaving offerings scattered throughout El Teide National Park.

The transition from the coast to the top of the peak is not as obvious as you’d think. I was surprised that I had not noticed how the city had fallen away before the scorched pines and snow began. But I was driving. If you’re looking for the easiest way to a great view, the drive along winding roads is fantastic. Alternatively, do it the traditional way and hike.

Near the summit of El Teide. Photo: Kristine De Abreu

The 040 route

Tour guides usually take hikers from Santa Cruz, the capital, to the hike’s starting point on the edge of the national park. However, if you want the authentic Guanche experience, you need to do the coast-to-summit trek, known as the 040 route. This trail is over 27km long and takes you to an altitude of 3,600m. It’s a tough trek, and you should not take the rapid altitude change lightly.

The starting point is Playa Del Socorro in Los Realojos in northern Tenerife. You’ll go through rural areas, farmland, and along remote roads. Eventually, you will stumble upon Las Cañadas del Teide, an area the Guanches used to store water, herd their livestock, and make tools out of volcanic glass.

As you approach the summit — depending on the time of day you arrive — you’re going to need a permit. Nighttime or early morning does not usually require a permit, but past eight or nine in the morning, you will need to purchase one. You can apply online, and it’s only a few euros.

El Teide from La Orotava. Photo: Kristine De Abreu

Anaga

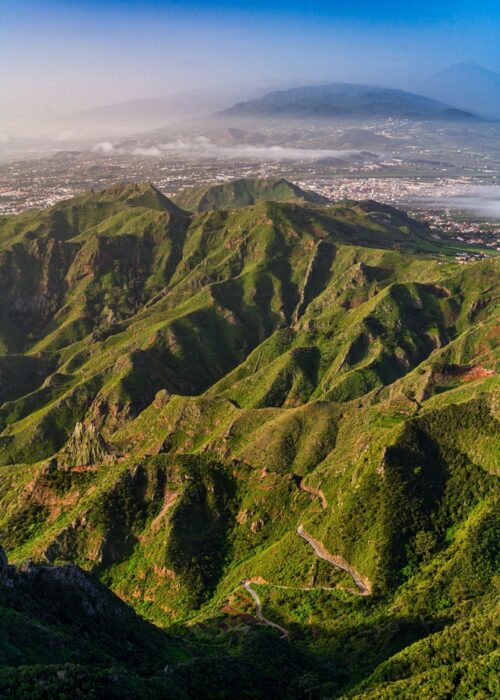

Anaga was one of nine Guanche kingdoms (menceyatos) in Tenerife. Guanches were cave dwellers, and Anaga’s dense, ancient laurel forests and jagged mountains provided the perfect place to hide from the Spanish. Beneharo, one of the sons of Tinerfe (after whom the island is named), was a king of Anaga who tried to make peace with the Spanish.

In Anaga, I found a labyrinth of twisting, moss-covered tree branches and dense foliage. The thick canopy blocked most of the sunlight, casting the forest in an eerie dark green hue. The Guanches hid in these parts for good reason.

Aerial view of Anaga. Photo: Shutterstock

An ancient forest

Calling this laurel forest old is an understatement. It is approximately nine million years old and contains the most endemic plant species in Europe. Anaga’s rugged terrain, shaped by volcanic activity, consists of ravines, sharp ridges, and coastal cliffs that have helped isolate and preserve a high level of biodiversity.

Among the most popular treks is the Sendero de los Sentidos (Path of the Senses). This part of the forest encourages hikers to engage their senses. The humidity casts the forest in a constant mist, the trees are so close together, and you can’t help but hear yourself think. Another favorite is the Chamorga to Roque Bermejo trail, with its panoramic views and ancient hamlets. Hikers can also take the Cruz del Carmen to Punta del Hidalgo trail, a descent from the heart of the forest to the coast.

The Anaga region encompasses 26 local villages and parts of the Santa Cruz de Tenerife, La Laguna, and Tegueste areas. In a small village called Afur, locals found a volcanic stele containing Guanche engravings, which are now in a local museum. The Guanches used the stone for mummification and funerary rituals, and it may have links to a Carthaginian deity, linking the Guanches to North Africa.

Cueva de Achbinico

I almost did not make it to Candelaria, but after several wrong turns, I drove down to the Plaza de la Patrona de Canarias. There, nine bronze statues stand on volcanic rocks as if guarding the town against the roaring Atlantic waves. Each sentinel is the likeness of a Guanche king and faces the Basilica of Candelaria.

The statue of the Virgin Mary in the cave in Candelaria. Photo: Shutterstock

According to legend, before the Spanish conquest, two Guanche shepherds found a statue of the Virgin Mary floating in the water off a beach called Chimisay. They brought it to their king, who placed it in a cave to be worshipped as their goddess.

When the Spanish came, they found the statue, and eventually the town was named after its patron saint, the Virgin of Candelaria. A replica of the statue is located in the cave adjacent to the Basilica.

Pyramids of Güímar

Here’s where the Guanche story gets a little strange. The Pyramids of Güímar are six structures built from lava stone without mortar. They’re not particularly high or even that impressive. However, this pyramid complex has sown division in the archaeological community.

Initially dismissed as simple agricultural terraces or piles of rocks cleared by 19th-century farmers, further investigation revealed their deliberate construction and possible ceremonial or calendrical functions. For believers, the pyramids are aligned with astronomical events such as the summer and winter solstices.

Pyramids of Güímar. Photo: Shutterstock

The debate about the pyramid’s history started when an already controversial figure read about them in a newspaper article in the 1990s. Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl made a name for himself thanks to unconventional ideas that he promoted through interesting nautical journeys in primitive boats. His Kon-Tiki expedition was not just revolutionary in demonstrating that ancient cultures and civilizations may have interacted, but also brought Tenerife into the international spotlight by noting potential links between the Canary Islands, Egypt, and pre-Columbian America. Heyerdahl thought the Guanches built the pyramids after interacting with people from Mesoamerica or Egypt.

Other archaeologists do not support this theory and attribute the structures to relatively recent agricultural activity in the 18th or 19th century. Despite this, Heyerdahl’s work led to the creation of the ethnographic Parque Etnográfico Pirámides de Güímar, a museum and cultural center that presents his theories alongside other information about pyramid-building cultures worldwide.

Cueva del Viento

If you get claustrophobic or easily spooked by the dark, the Cave of the Winds is not for you. The Cueva del Viento is one of the largest volcanic tube systems in the world and is located in Icod de los Vinos, below El Teide.

Formed by lava flows from the Pico Viejo volcano, the second-highest peak on the island next to El Teide, the cave extends over 17km. It features a complex labyrinth of passages and is known for its unique geological formations, including lava stalactites, terraces, and lava lakes.

The Guanches used these tunnels, and excavations uncovered artifacts and remains.

The Cave of Wind lava tube. Photo: Ondrej Prochazka/Shutterstock

Archaeologists and paleontologists have found fossils of extinct animals, such as the giant lizard (Gallotia goliath) and giant rat (Canariomys bravoi) in the Cave of the Winds, providing insight into the island’s prehistoric ecosystem.