Hugh Wilson has spent the last 30 years regenerating native forest on New Zealand’s Banks Peninsula. The story of how he did it is the subject of a lovely little 30-minute documentary called Fools and Dreamers: Regenerating a Native Forest. It’s the perfect watch for anyone who needs their faith in humanity (and humanity’s ability to fix its mistakes) restored.

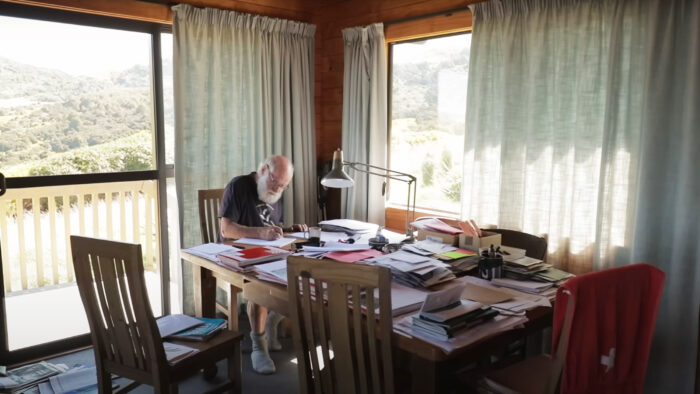

With his unfailingly cheerful nature, white beard, bald head, glasses, and propensity for mixing long-sleeved flannel shirts with shorts, Wilson looks like a well-loved grandfather. But he’s so much more than that.

Interested in plants from an early age, Wilson channeled his dual love of art and science into a thriving life as a botanist. He spent the first half of his career conducting detailed studies of the plant life on the Banks Peninsula — a region that used to be heavily forested but, by the late 1990s, was mostly farmland colonized by invasive plant life.

Photo: Screenshot

Starting from nothing

“Both Mauri and European settlements had a huge impact on the forest, so by 1900, less than one percent of the old-growth forest [on the Banks Peninsula] was left,” he notes.

Then, an acquaintance asked if he’d be interested in running a private nature preserve. The goal? Bring tapped-out pasture back to the way it looked 800 years ago. And do it fast, because New Zealand had already permanently lost some of its native species of plants and animals.

“Some people say, well, why are you restoring the forest? It’s kind of like asking why you should love your mother,” Wilson says in the film. “We’re totally, totally dependent on the vegetation and wildlife that supports our own lives.”

So he hopped at the chance to manage the Hinewai Nature Reserve, a piece of land that would eventually cover 1,500 hectares. But there was some pushback.

Photo: Screenshot

Naive greenies?

“I am all for saving patches of bush, but the thought of starting from scratch on land that is clear enough to be used productively frankly appalls me. As for shutting up a whole valley, heaven help us from fools and dreamers!” one newspaper letter, written by a local farmer at the time, said.

“I think they basically thought we were naive greenies from the city. I’m sure they thought we’d come here with all these ideas, and within a year or two, we’d find out it was all just too hard, and it wasn’t happening, and we’d [leave] again. Now here we are 31 years later. I looked at it as a great compliment because we need a few more fools and dreamers in the world,” he notes.

Photo: Screenshot

The solution? Gorse, of course

The key to Wilson’s plan was counterintuitive. The landscape he wanted to turn back into native forest had been used as pasture for generations and was also infested by gorse, an invasive flowering plant that grows quickly and renders pastures unusable. Many people thought he was nuts for not beginning his reforesting by trying to get rid of the gorse.

“Gorse is a terrible weed for pastoral farming. And no one, let alone me, would deny that. But nothing is black and white, is it? If you’ve got it, and it’s kind of infested the landscape, then it’s worth looking at its good points and saying, ‘Well, maybe we don’t have to fight it,'” he remembers. “We don’t want pasture, we want the native forest to regenerate, and gorse is a wonderful nurse canopy for native forest regeneration.”

This is why botanists are handy to have around. Wilson knew that gorse is a nitrogen fixer, meaning it fertilizes the soil it inhabits. It grows quickly and creates sheltered spots for shade-tolerant hardwood saplings to grow. But it has to have full sunlight to stay alive. So once native trees in the preserve sprout up beyond the gorse canopy, the invasive weed dies. It’s a brilliant, elegant solution, and Wilson’s spent the last three decades making it happen.

Photo: Screenshot

Wilson’s routine

There are no motorized vehicles in the nature reserve, so Wilson begins each day with a walk to his current work site — a journey that sometimes takes him as much as two hours. He works all day and then treks back home. After dinner and a pipe, he turns to his management tasks, handling piles of the Hinewai Nature Reserve’s paperwork late into the evening. Then he goes to bed, gets up, and does it all over again.

Photo: Screenshot

The result is spectacular. The once dry, grassy land in the reserve has largely returned to the lush forest it once was. Streams flow, even in the dry season, and there are 47 waterfalls on the property (that Wilson has found so far). And from the very beginning, the reserve has been open to the public.

Photo: Screenshot

“I think the community is now by and large in support of Hinewai,” a local farmer says toward the end of the film. “We realized that the way farming was done over the years had to be changed. And I think what [Wilson] has done is helped people realize that it can be done. In a good way.”