Waterwalker is a 1984 feature-length documentary from Canada’s National Film Board. In this beloved classic, filmmaker and naturalist Bill Mason paddles through Ontario’s wilderness, reflecting on art, nature, and the exploration of the natural world.

On the screen, we see Mason’s art, film, and painting as he begins to discuss his ongoing attempts to share his experiences with nature. Originally a commercial artist, nature exerted an inescapable pull on him. He spent months at a time in the wilderness, taking commercial work to support his next trip. Then he turned to film as a way to transmit the beauty he saw.

Mason used palette knives to paint, capturing vibrant, impressionistic plein-air landscapes. Photo: Screenshot

“The problem with film,” Mason reflects, as he adds the final refinements to a landscape painting, “you show it the way it is, everybody goes off to sleep.”

Once, Mason remembers, he showed his footage to producers. They immediately began trying to add drama — plane crashes, broken legs, wolf attacks — to Mason’s disgust. The producer’s ethos is fundamentally opposed to Mason’s work, which, he says, has no villains.

“Just you and me,” Mason promises, paddling Lake Superior and the waterways of Ontario.

Following the water

The canoe is a literal vehicle for Mason but also a vehicle to explore his thoughts on spirituality, the natural world, artistic inspiration, and the timeless appeal of water. Starting on Lake Superior, he begins making his way upriver, reaching toward an unknown headwaters.

While Mason broadly works his way north, the film does not follow a particularly linear narrative. Instead, it winds along, stopping to examine a striking image or explore a line of thought.

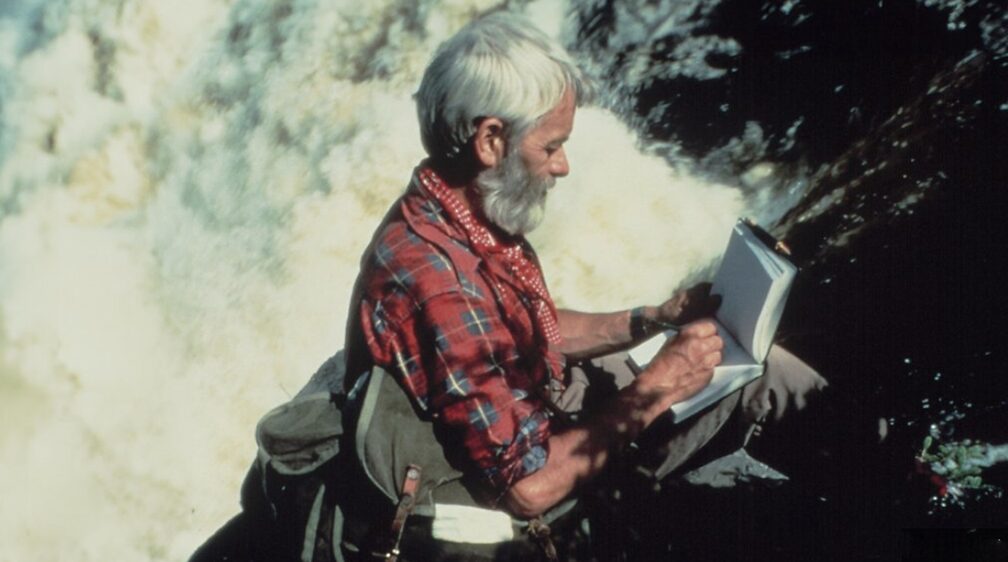

Bill Mason at work. Photo: Screenshot

Amidst wildlife encounters, tipped canoes, and painting sessions, he continually returns to his canoe. It’s a traditional wood-and-canvas affair. While he admits it isn’t as practical to lug around as the modern alternatives, his aesthetic sensibility is compelled by its lines. In a similar vein, he dismisses modern tents as “doghouses,” in favor of an old-fashioned open-front A-frame tent — variously known as a Baker tent, Labrador tent, etc.

“Anyone who tells you portaging is fun,” Mason says, “is either lying or crazy.” Photo: Screenshot

Environmentalism drives Mason’s desire to show nature’s beauty to an audience. Both his paintings and his filmmaking entreat the viewer to understand and care about the land. On his journey, he sees birch trees struggling and hears about acid rain.

“You see for yourself what we’re doing to the land.” Even a seemingly pristine waterfall, far from civilization, is bittersweet, because one day he knows ravaging progress will find it.

Bill Mason passed away in 1988, at only 59 years old. Over thirty years later, his work, especially his documentary films like Waterwalker, remain iconic staples of the genre. His message — the need to learn how to love and live with the natural world — has never been more relevant.