This week’s documentary takes us to the frozen Arctic, where a modern expedition follows the route of early 20th-century explorer Hubert Wilkins. In 1931, Wilkins set out for the North Pole in a repurposed military submarine. The subtitle of Frozen North — “The Disastrous Attempt To Reach The North Pole In A WW1 Submarine” — hints at how well they fared.

The ‘Nautilus’ submarine descends into Arctic waters. Photo: Screenshot

A promising adventurer

Wilkins was raised in Australia. The son of a sheep farmer, he was a self-taught pilot, photographer, and explorer with an abiding interest in the weather. Wilkins first made a name for himself when he flew from Alaska to Spitsbergen, completing the first trans-Arctic airplane flight. He immediately launched himself into the next adventure: reaching the North Pole by submarine.

He chose an old WW1 submarine, which he rented from the U.S. Navy for $1 a year. Interested in his plans, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst promised Wilkins $250,000 — worth over $5 million today — if he could actually reach the North Pole.

The ‘Nautilus’ at her naming ceremony. The event was attended by the grandson of Jules Verne, whose book, ‘20,000 Leagues Under the Sea’, inspired the name of the vessel. Photo: Screenshot

Feted in Brooklyn and well-wished by the wealthiest men of the age, the newly christened Nautilus headed North. Wilkins’ goals were scientific. He believed, correctly, that polar conditions impacted weather worldwide.

In addition to his meteorological instruments, the ship was fitted with an ice-borer which didn’t work, a hydraulic flap to keep it below the ice, and an airlock from the converted torpedo bay. It had no heating or insulation.

The Loch Ness Monster. Just kidding. It’s the hydraulic flap. Photo: Screenshot

The disastrous attempt

Her sea trials went badly, but the season was getting late. It was forge ahead or wait another year, and no polar explorer has ever chosen option two. They left New York with only two months of summer left, with 10,000km to go.

After only a week, the ship is caught in a storm, and the engines fail. Photo: Screenshot

Almost immediately, a storm nearly wrecked them, and the Nautilus sent out an SOS signal. They were rescued and towed the rest of the way to England. Once there, they lost a month to repairs, only halfway to the North Pole. They kept going anyway, making it to Bergen, Norway. Norwegian experts doubted they would survive, and Randolph Hearst sent Wilkins a telegram telling him to call it off. Wilkins ignored this.

The ‘Nautilus’ leaves Bergen, with public confidence at an all-time low. Photo: Screenshot

It was freezing in the hold, where Wilkins and the researchers conducted observations. They actually did important research, including showing that the Earth is flattened at the poles, instead of a perfect circle. Hopefully, this achievement consoled them through the miserably cold, wet, and cramped conditions.

After doing some science and freezing in the Arctic Ocean, the crew was ready to go home. But that wouldn’t satisfy the press, so Wilkins ordered a dive. They were going under the ice.

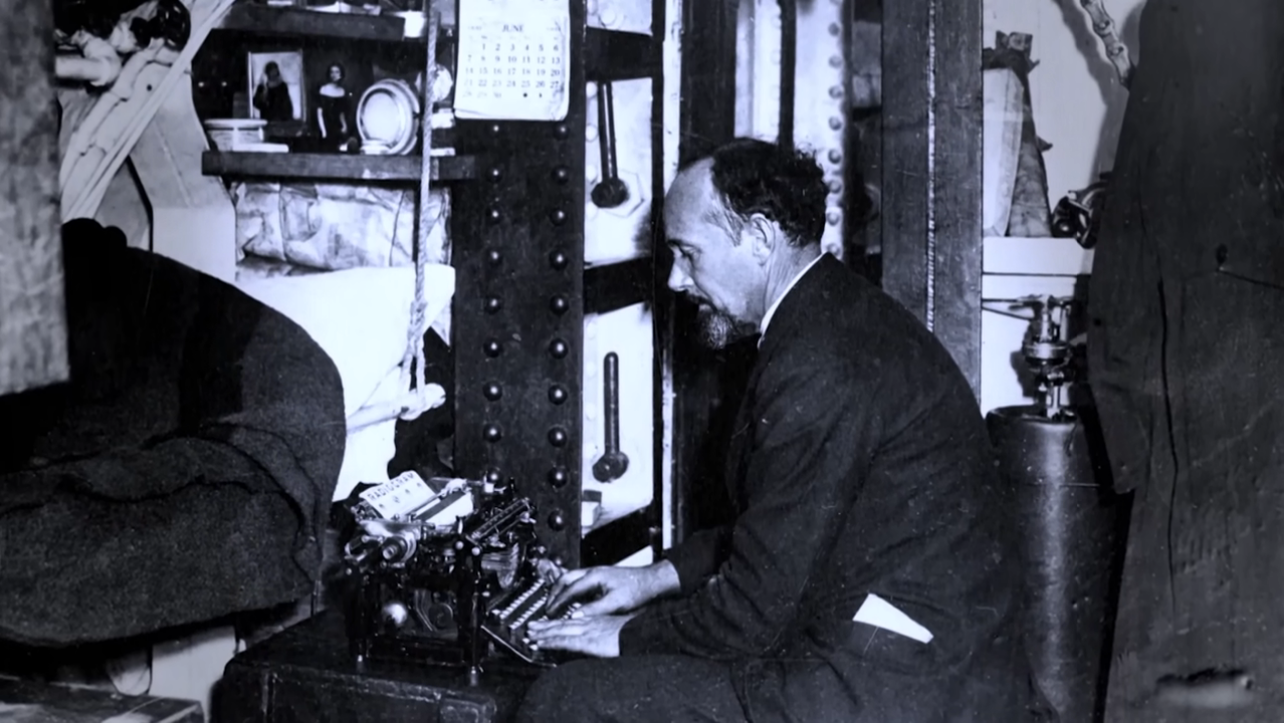

Sir Hubert Wilkins in the ‘Nautilus.’ Photo: Screenshot

Under the ice and missing the Pole

Upon inspection, however, Wilkins found the steering mechanism damaged. Historians in cutaway interviews suggest that this was deliberate sabotage by an engineer anxious to go home. Wilkins was unmoved and ordered a dive on the next calm day.

They made it under the ice, becoming the first people to do so. But the radio was damaged, leaving them unable to call for help. At home, newspapers reported them dead.

To prove they’d gone under the ice, Wilkins filmed them going under just a few meters. Photo: Screenshot

When they re-emerged, they jury-rigged a radio announcing they were alive. Hearst signaled back that he was glad they were alive and was also cutting off funding. Devastated, Wilkins stayed in the ice for three weeks, taking groundbreaking scientific measurements. It was clear they were not going to reach the Pole.

The Nautilus left the frozen north and limped back to Norway. By the time it arrived, another engine failure had left it unusable. On order of the U.S. Navy, it was scuttled off the coast of Norway.

Diving to the Nautilus

Nearly a century after his failure to reach the Pole, Wilkins’ attempt is appreciated as an exploratory and scientific success. But the mystery of the broken steering mechanism lingers.

In a modern two-man submersible, researchers descend to the sunken Nautilus. The modern craft contrasts sharply with the dangerous, dirty, and miserable conditions of the older one, showing how far (with some exceptions) the technology has come.

They found the Nautilus, well preserved in the cold water, but now home to a diverse array of marine life. Researchers focused on the steering gear, looking for signs of deliberate damage. But it’s buried in the sediment, preventing them from inspecting it.

The hatch of the ‘Nautilus’, rediscovered off the coast of Norway. Photo: Screenshot

Sabotage or not, it was suicidal to dive without those diving rudders, explains oceanographer Raphael Plante. Coming back alive at all was a remarkable achievement.

But Wilkins always dreamed of returning, and proving that submarines were a viable way to explore the North Pole. In March of 1958, a year after Wilkins’ death, U.S. Navy submarine USS Skate reached the North Pole. They scattered Wilkins’ ashes there.

Later that year, his vessel’s namesake, the USS Nautilus, became the first submarine to transit under the North Pole.