It’s been almost 30 years since the 1996 storm on Mount Everest claimed the lives of eight people: guides Andrew Harris, Rob Hall, and Scott Fischer; clients Doug Hanson and Yasuko Namba; and Indo-Tibetian Border Police officials Subedar Tsewang Smanla, Lance Naik Dorje Morup, and Head Constable Tsewang Paljor.

Over the years, the survivors have penned conflicting accounts, documentarians have created films, and major Hollywood studios have even attempted dramatic retellings of the story.

A summit photo from the Adventure Consultants 1996 Everest Expedition. Photo: Screenshot

So you may think you’ve learned all there is to learn about the disaster. But for a glimpse at the immediate physiological and physical impact the event had on some of the climbers stranded on the mountain during that fateful season, look no further than this 60 Minutes Australia special.

Recorded in 1996 in the abrupt aftermath of the disaster, it draws heavily on interviews from Adventure Consultants guide Michael Groom and clients John Taske and Beck Weathers.

A tangled timeline

You could spend days unraveling the timeline’s tangled threads (and people have). But if you’re just tuning in, the broad strokes go something like this: guides and clients from multiple outfitters became stranded at high camps while descending from summit attempts when a major, multiple-day storm blew in unannounced. Confusion, hardship, and death followed. In the aftermath, serious conversations ensued about ethical climbing and who, exactly, belongs in one of the world’s most extreme environments.

The short is only 16 minutes long, so after outlining the scenario, it quickly homes in on the stories of Groom and Weathers.

At the time of the expedition, Groom had successfully summited more Himalayan peaks than any other Australian. And though he recounts the story as placidly as perhaps only an Ozzie can, you can see that the shock is still very much present within him.

By the time of the 1996 expedition, Groom had already lost all ten of his toes. Photo: Screenshot

In a confusing series of events, Groom was forced to abandon two of his clients, Weathers and Japanese climber Yasuko Namba, 500m above Camp 4, as he stumbled on for help. After reaching the camp, the exhausted and hypothermic Groom dispatched two other climbers to search for Weathers and Namba. The stricken climbers were found, but the fatigued rescuers judged them too close to death for a successful rescue and returned to Camp 4 alone.

Left for dead

Namba died there in the snow above Camp 4, but unbeknownst to anyone, Weathers later regained enough strength to claw his way to his feet. He was totally unaware there had been a rescue attempt and determined to press on.

“I thought to myself, I’m going to face into the wind, I’m going to walk forward, and I’m either going to walk off this mountain or walk into a tent, one of the two,” Weathers says in his interview.

The Texan, snowblind and severely frostbitten, somehow made it to Camp 4 the next afternoon, where he shuffled into a tent and passed out with a sleeping bag over his face.

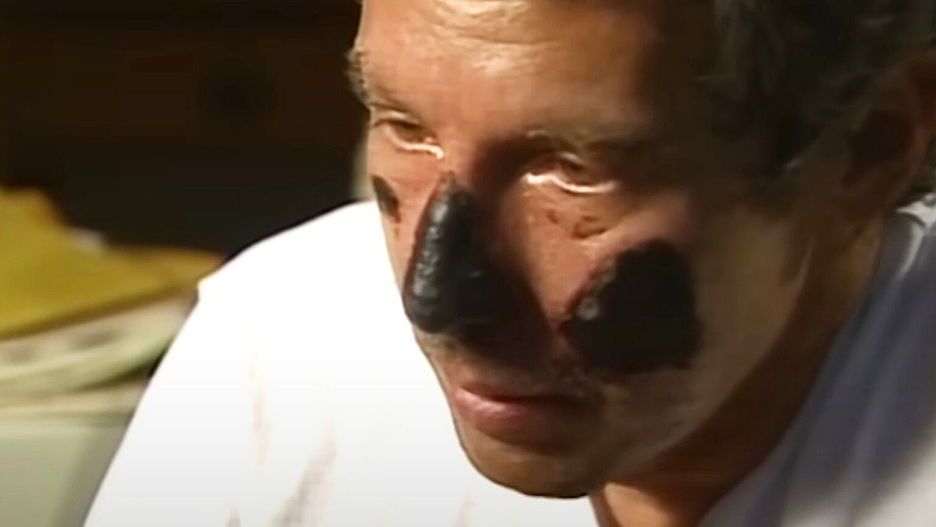

A badly frostbitten Beck Weathers in his 60 Minutes Australia interview shortly after the disaster. Photo: Screenshot

The following morning, Groom shepherded the rest of his clients further down the mountain, eventually reaching Camp 2 and medical assistance. But not before exhaustion and bad luck led him to make a controversial decision. Making his rounds at Camp 4 before departing, Groom happened upon the tent where Beck had blindly sought shelter.

“I looked into a tent that was open; I saw a body lying on the floor of the tent with a sleeping bag over the face of the body. For a moment, I hesitated as to whether I should look at the body to see who it was, but I decided not to. I had assumed he was one of the American party who had passed away during the night.”

Beck was eventually rescued by French climbers from Camp 3.

Guide Michael Groom shares his story. Photo: Screenshot

Conscience clear

One of the most fascinating moments in the short occurs when the interviewer questions Groom about this moment. Groom insists that his conscience is clear and that he did everything humanly possible to care for his clients. The 60 Minutes interviewer presses again.

60 Minutes: “Even though you left him for dead? Twice?”

Groom: “No. I didn’t leave him for dead twice. The first time, it was a group decision that I should head off to find Camp 4 because I was the strongest both mentally and physically. The second time, I didn’t leave Beck for dead because I didn’t even know he was there.”

Here, Groom pauses, and you can see the emotion roiling beneath his stoic features.

Groom: “In some ways, I wish I’d have removed the sleeping bag and identified him, and then I could have taken care of him, but that’s something I didn’t do. And I have to live with that decision.”

Weathers: a correct decision

For his part, Weathers agrees.

“I think it was a correct decision for him to go try to help everybody. And I’m not surprised when he saw me the second time that he thought I was already gone,” he says.

This moment is particularly impactful because Weathers, at the time of the interview, had yet to undergo the dramatic surgeries that would leave him with an amputated and reconstructed nose, an amputated right arm, and missing all the digits on his left hand.

Instead, in the 60 Minutes footage, his arms are swaddled in bandages, his face blackened and gruesome. Toward the end of the short, he chats with Groom and professes hope that his amputations will be limited. It’s heartbreaking and immediate in a way that reading and watching later accounts don’t quite reach.

Photo: Screenshot

The special wraps with the thought that has plagued Himilayan mountaineering ever since.

“The deaths of such experienced climbers as Rob Hall have raised serious questions as to whether adventurers who pay for the experience put not only themselves in danger but also those who guide them,” the host says.

That we still have this debate today indicates that despite all the media coverage of the 1996 Everest Disaster in the 18 years since it occurred, perhaps the most important question about it remains unsettled.