There was only one summit push on K2 this year, very late in the season and in uncertain conditions. The push came after half the climbers in Base Camp called off their attempts. Three small commercial teams reached the summit on August 11, and a single independent climber followed 24 hours later. The final part of the descent was a sort of russian roulette: of the 40 climbers, one lost her life, and several were injured by constant rockfall.

We have asked those who were on the mountain about the bittersweet season.

Rising temperatures and tension

The climbing season in the Karakoram was characterized by excessively high temperatures, which severely impacted conditions. The climbing was particularly poor to 6,000m, and negatively affected the climber’s acclimatization process, particularly those climbing without supplementary oxygen.

There was also a general lack of communication, both because of intermittent connections and intentional secrecy on the part of the international companies operating on the mountain.

Moreover, the scarce communications hinted at a tense atmosphere between commercial expeditions, determined to put their clients on the summit, and independent climbers. The independent climbers were typically outfitted by small local companies to Base Camp, but progressed up the mountain on their own — yet using the ropes fixed by the larger teams.

The patience game

The lack of good climbing days tested climbers’ patience, especially those who arrived early and those planning to climb without supplementary oxygen, who needed more acclimatization rounds before considering a summit push. A delay to the rope fixing and increased rockfall risk tested many climbers’ motivations.

“This year, because we arrived at K2 Base Camp a bit late, we didn’t have to wait as long as others,” Mingma G of Imagine Nepal told ExplorersWeb. He says his team would have been ready to launch a summit push as soon as July 25 if the weather had been good, but they were also fine with waiting as long as required. “I think Prakash Sherpa’s team and our group were the only two teams who were quiet and waiting patiently, with no pressure,” Mingma G said.

In a recent interview with ExplorersWeb, Sohail Sakhi of Pakistan said that some clients’ impatience pressured other teams. “Some of the teams had spent so much time at Base Camp and were not properly acclimatized. [They] were requesting other teams cancel their expeditions as well so as not to disappoint their clients,” Sakhi noted. He praised Mingma G’s determination: “Mingma G was a key decision maker in planning for the summit push, ensuring he had the most up-to-date forecasts, and was very clear with his own team on plans and expectations for the summit push.”

Elite Exped also thanked Mingma G, stating that without him, there would be no summits on K2 this year.

Mingma Gyalje Sherpa, known as Mingma G, at K2 Base Camp. Photo: Sohail Sakhi

Other climbers didn’t get along so well.

Points of view on the rope debate

Mingma G accused some climbers in Base Camp of being “rope parasites.”

“We were in communication with all the Nepalese leaders, but it was different with individual climbers. Some called themselves alpinists, and they were there without ropes,” Mingma G said. He contrasted these ropeless climbers to David Gotler, who — together with Typhaine Duperier and Boris Langenstein — climbed Nanga Parbat in alpine style via the Schell route from the Rupal face. “I respect these real alpinists,” Mingma G said.

“What the expedition leaders don’t say is that we offered to contribute to the rope-fixing works and were very rudely refused,” independent French climber Serge Hardy replied. “I was willing to carry coils of rope, even fix some, but I was rudely dismissed.”

Serge Hardy at K2 Base Camp. Photo: Serge Hardy

Hardy was on his third K2 climb. He recalled that on his two previous K2 attempts, he contributed by buying rope in Skardu; on Gasherbrum II, he climbed with a small team and fixed some pitches on the Banana ridge section. “If it was agreed, I was willing to pay for the ropes, but when we tried to offer solutions, we were rejected. They didn’t want our help; they just wanted us off the mountain.”

Hardy was using private weather forecasts, which he says he offered to share with the bigger teams, to no avail.

Mingma G shared what he recalled of the discussion:

“The French guy [Hardy] came to our dining tent and asked me about my plan. I asked him the same question, and if he had ropes, but he had none. Then I asked him why he was on K2 without rope, and his reply was, ‘this year is special.’ I replied to him, ‘we collect rope, every team contributes, and we climb together, and it’s the same every year.’ Nobody can climb K2 without rope. I didn’t talk with him further because it was meaningless.”

Little communication?

Asked to provide his point of view, Sohail Sakhi admits that communication at Base Camp was nearly non-existent between teams. “Independent climbers would rely solely on commercial teams’ plans…we were repeatedly asked what our plans were, and when asked the same, they would tell us they had none and were waiting on our pushes,” he said.

Hardy also mentioned the commercial teams were very secretive about their strategy, which caused some stress during the summit push. “I could understand teams wanting to keep their strategy to themselves in years with lots of people [because of the] fear of crowding, but we were very few in Base Camp. There was no need.”

Asked about the issue, Sohail Shakhi was blunt: “Every climber and every company goes into the mountains understanding they need to make decisions for themselves, but this year, it seemed like there was an expectation that they would ultimately rely on one company above others and thus the blame for any accident would also fall on that one company.”

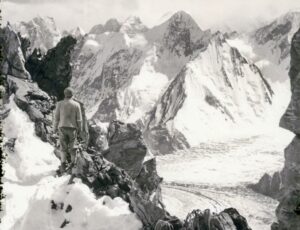

Views from high on K2. Photo: Sohail Sakhi

Fenced Camp 1

Hardy also pointed out an unpleasant method used by commercial teams at Camp 1, located on a scree slope where space for tents is scarce. “I was among the first climbers who reached Base Camp, yet, when I climbed to Camp 1 to pitch my tent, I discovered the best patches had been surrounded with poles and wire ‘reserving’ the space,” he said. “I managed to find a sketchy spot to plant my tent on a tilted slope, and yet, when I returned days later on an acclimatization rotation, I found my own tent surrounded by these wires!”

Hardy shared some pictures and a video (below) filmed by another climber showing tents surrounded by wires and snow poles:

“On K2, it is first-come, first-served. There are limited spaces, so whoever reaches [camp] first, they put their tents up first,” Mingma G replied. “Reserving a place doesn’t make any sense.”

Risk Tolerance

In the end, all climbers, each in their own style, share a common goal for which they prepare for months, physically, mentally, and financially. Yet, the perception and management of risk vary from person to person and depend on experience, skills, and priorities.

“Risk tolerance for an independent climbing team should be quite different from that of a guided expedition,” Ryan Waters of Mountain Professionals said. The U.S.-based company aborted its K2 expedition after an avalanche killed a member of their staff and injured three other climbers.

Waters also points to a gut feeling experienced guides have. “Sometimes things just don’t feel right, and this is magnified on K2. At that point, when the red flags are popping up, then maybe it is better to call it a day on this specific hill,” he said.

Disaster lurking

“Most guides bring an Everest mindset to the Karakoram, thinking that manpower and ropes will take people to the top eventually, but this peak has certain under-the-radar vibes that are different, and need to be accounted for when deciding to go or not to go with a group of clients,” Waters said.

“If conditions are perfect, then, yes, it is just a physically demanding ascent, but once one or three of those red flags start stacking, it can be a lurking disaster. That might be the question that emerges from this dry, dangerous season: rockfall accidents happened not just on K2, but on other mountains, and the line between success and tragedy was often mainly luck,” Waters concluded.

While not on K2 this year, Ralf Dujmovits of Germany has also felt disaster in the air for decades. “The rockfall hazard was well known for most of the summer, by the guides and the clients, so they all chose to play this well-known high-risk tolerance game,” the 14×8,000’er climber told ExplorersWeb. “This dangerous game of climbing K2 despite various bad conditions has been going on for decades, so there was nothing new for this season.”

K2 in the moonlight. Photo: Imagine Nepal

Reasons to leave

Likewise, a significant number of climbers eventually made the call to pack up and go home. Caroline Rinfeldt of Denmark, a client with Elite Exped, explains her difficult decision.

“K2 has been a childhood dream, I always felt extremely connected to the mountain…but the conditions this year just weren’t good, many people had been injured and a person died, and I am aware that climbing in August is riskier than in July,” Rinfeldt said. “So, when we looked into a summit push after August 7, I felt the mountain told me it was time to leave. It felt that climbing would be a gamble with extreme risk rather than living a childhood dream.”

Caroline Rinfeldt (right) and Vinayak Malla at Base Camp. Photo: Caroline Rinfeldt

Reasons to stay

Yet, Elite Exped continued with the summit push, led by Vinayak Malla. Malla reached the top with Kirsty Clack, Charles Page, Phuri Sherpa, and Nima Sherpa. Asked about the push, the company provided a corporate reply:

“All climbing and mountaineering comes with risk, but we put stringent protocols and procedures in place to mitigate these risks as much as possible.”

Dry, dangerous conditions on K2 this year. Photo: Sohail Sakhi

Nepalese coordination

“We worked with all teams on the mountain to coordinate our approaches for the summit and for the descent — which is vital when conditions are bad, as was the case this year — to ensure everyone’s safety,” Elite Exped said, explaining that they were in constant contact with Mingma G over InReach, especially for the descent, when they decided to go together. “The idea was that if anyone loosened a rock, the team would be together and so that rock could not hit anyone below,” Elite Exped explained.

House’s Chimney on K2, totally dry in summer 2025. Photo: Sohail Sakhi

“Also, if you come down at night, that means that the snow is frozen and is holding the rock, which minimises the risk of rock fall,” Elite Exped said.

The K2 summit teams did descend at night, yet it was not enough. It was pitch-black when Jing Guan was killed by a falling rock. Several climbers then reported that Mingma G told other teams to wait in Camp 2 for first light, to proceed with some visibility.

Fixing works: who did what

“The route was only fixed to Camp 2 before we arrived at K2 Base Camp on July 8,” Mingma G explained. “We finished acclimatization by July 15. On July 18-19, Madison Mountaineering and our team fixed the rope to 7,100m, completing all the rocky sections.”

The rest of the way to Camp 3, some 400 vertical meters, was described by Mingma G as easy, and they left it unfixed because they expected the ropes would be buried if it snowed.

Frame from a video by Sona Sherpa sent from near the summit of K2. Photo: Sona Sherpa/Seven Summit Treks

Members in six companies waited: Seven Summit Treks, Elite Exped, Alpinist Climber Expeditions, Laila Peak, Alpine Adventure Guides, and Imagine Nepal. Everyone who waited made it to the top on August 11 and 12, except for Israfil Ashurli of Pakistan.

Siddhi Bahadur Tamang, a Nepali staff member working for Madison Mountaineering who had remained in place after the rest of his team left the mountain, helped fix the ropes and made it to the summit for a record seventh time. According to the Everest Chronicle, Tamang “descended in under 12 hours to beat his permit deadline, narrowly avoiding a deadly rockfall that struck other climbers.”

On summit day, the rope-fixers were Tamang from Madison Mountaineering, Tsering Sherpa from Prakash Sherpa’s team, Vinayak Malla from Elite Exped, Sohail Sahki of Pakistan, Pasang Nurbu from Seven Summit Treks, and Mingma G from Imagine Nepal, according to Mingma G.

The trap: changing conditions

“When we fixed the section above Camp 3 on July 19, conditions were perfect. The risk was only present below Camp 1, but that section is almost the same every year,” Mingma G noted. “Kami Sherpa from Pangboche broke his hand there in 2015, another Sherpa climber broke his leg in 2022, and many are hit and hurt by falling rocks every year.”

“We were hoping for heavy snow on August 5 or 6, but later the weather changed and there was no snowfall, which was a huge disadvantage,” Mingma G explained. “However, our summit day was a perfect weather window. We had clear skies, no clouds, no wind, and a full moon that made that night very bright and clear.”

The climbers summited on August 11 through the afternoon, and Serge Hardy followed one day later. The real challenge came with the descent.

“When we went up for the summit push, the conditions were totally different from those found on descent,” Mingma G said. “There were rockfalls in the daytime but not during the evening and at night. Sohail and I climbed to Camp 1 in the evening, checking the potential rockfall, and we saw it was actually very safe.” Serge Hardy and Sohail Sakhi confirmed this point.

“On the way down, it was totally different,” Mingma G admits.

All the climbers we spoke to confirmed that the conditions changed quickly because of warm temperatures while climbers pushed for the summit.

Nightmare descent

“Standing on K2 was like touching the sky, but the way down was pure hell,” wrote Lenka Polackova of Slovakia, who summited with Sherpa support but no supplementary oxygen. “A few sunny days at the summit window changed the lower passages beyond recognition, into a trap that didn’t want to let us go home.”

Polackova wrote that the risk of rockfall extended from below Camp 1 all the way to Camp 2. Even descending climbers became a hazard, as they could let rocks fall on climbers progressing below. “[The rocks] were always preceded by a whistling sound that I had never heard anywhere before,” she said. “Below Camp 1, massive rock avalanches were added: two of them flew over me and Tsering (working for Prakash — we descended together).”

Making things scarier, they couldn’t see the falling rocks as it was pitch black during the night. Polackova admits both she and Tsering Sherpa prayed.

Polackova and Tsering were also the first to arrive at the side of Jing Guan. A falling rock had instantly killed the Chinese climber. “I will never get that image out of my mind,” Polackova wrote. Another rock hit Polackova’s husband, Jan Polacek, on the ankle. Several other climbers reported sustaining injuries during the descent.

“A rock hit my member (Jing Guan) just below Japanese Camp 1. If she had descended 20m more, she would have reached a safe area,” Mingma G said. “Climbers were descending ahead of her and behind; she was in the middle, and the rock hit her, so it was an unfortunate accident.”

Mingma G (right) with Jing Guan of China at K2 Base Camp. Photo: Jing Guan