Early explorers weren’t just worried about storms, starvation, mutiny, scurvy, wild animals, and all the other terrible fates that could and did befall them. They were also on guard against the monstrous humanoids that they thought lived just beyond the borders of the known world.

Before satellites and cameras, before accurate maps or reliable transportation, before modern understandings of biology and evolution, it was easy to think that anything could be out there.

Over thousands of years, a mythology of “monstrous peoples” evolved from the tales of historians and explorers. Today, few remember the whimsical imaginings that haunted the edges of maps. But as recently as the 18th century, they were considered very real dangers.

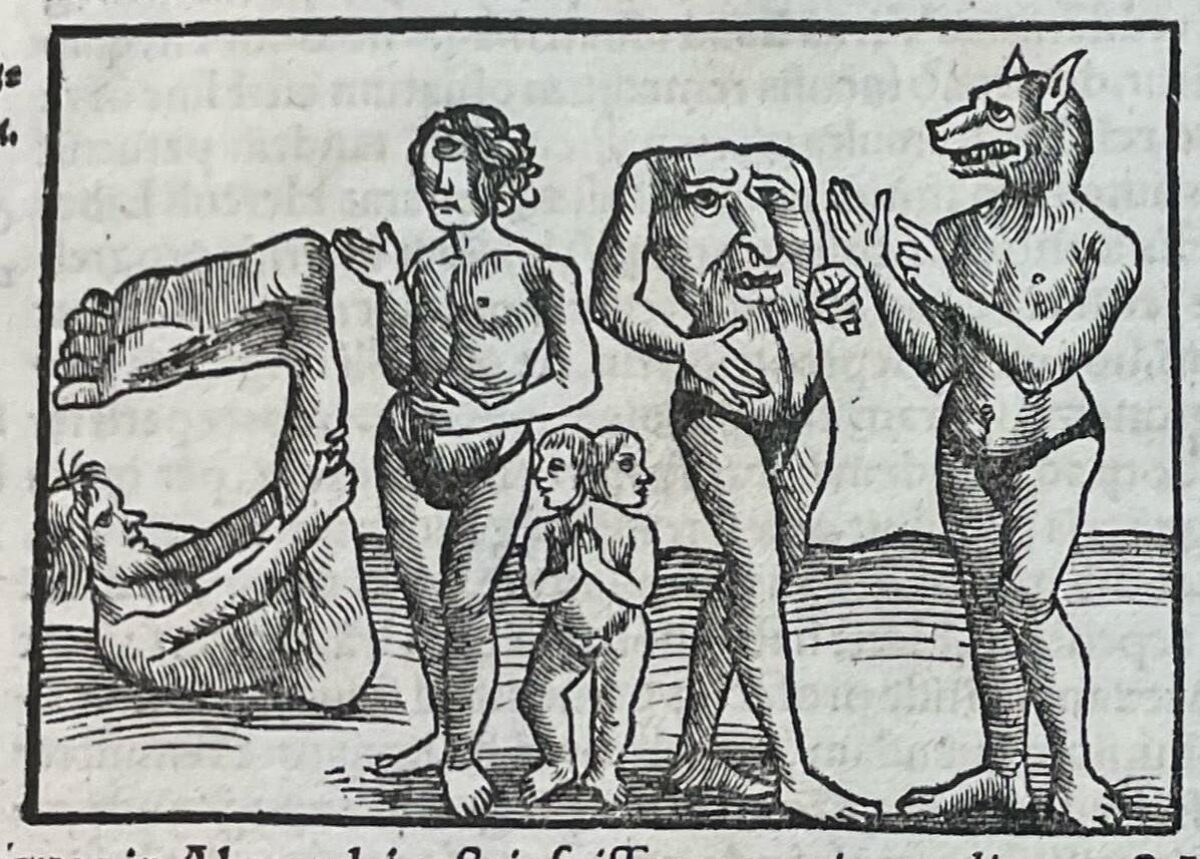

Five ‘Monstrous Peoples’ from Franciscan monk Sebastian Munster’s 1544 work, ‘Cosmographia.’ Photo: Royal Museums Greenwich

Monsters from the ancient world

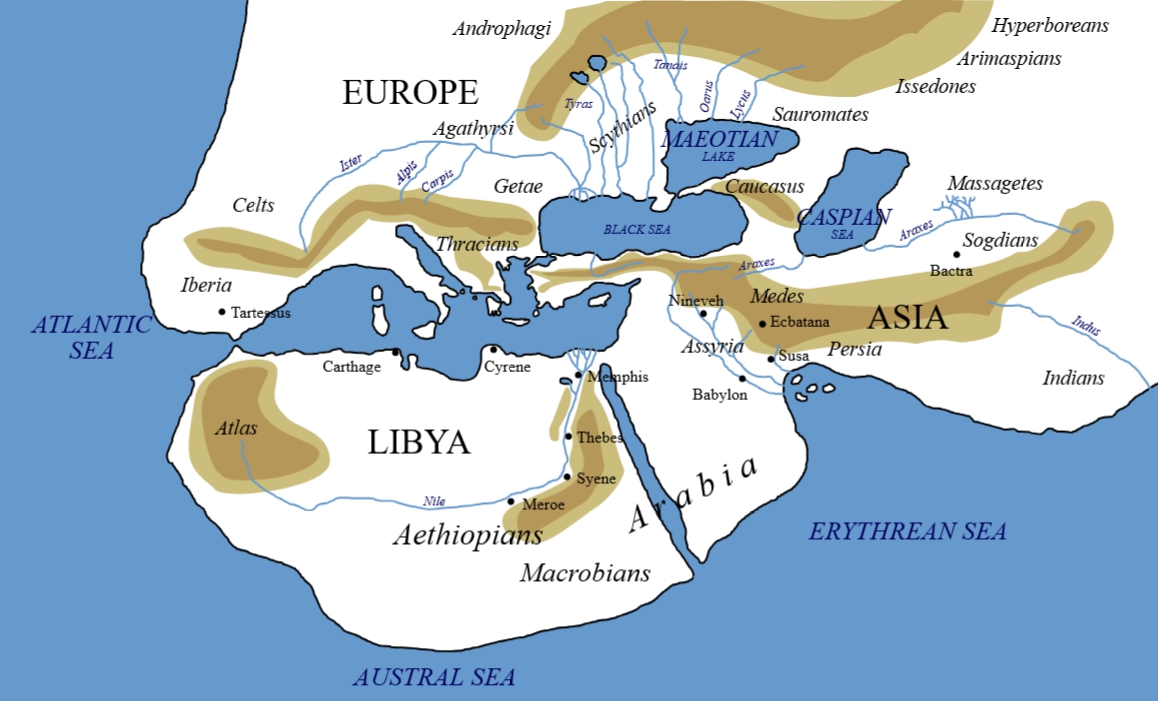

Travelers’ tales seem to grow more warped and fantastical the farther out they go from their starting point. Fifth-century BCE historian Herodotus wrote about traveling from his birthplace in modern-day Turkey to the boundaries of the Classical world. He records stories of giant ants in India, flying snakes in the Arabian peninsula, and half-lion, half-eagle griffins in North Africa.

He’s somewhat skeptical about repeating these claims. Nevertheless, he writes, “the ends of the earth produce the things that we think most fair and rare.”

The people also grew stranger with distance. On the border between Egypt and Ethiopia, he heard reports of “Troglodytes,” cave-dwelling people whose language sounded like the squeaking of bats and who ate snakes and lizards. In India, he had heard, some tribes ate their friends and family if they became sick or weak.

The line between human and monster grew thinner as he got farther. Later writers built upon the corpus of monstrous peoples. In the imaginations of Europeans, the edges of their maps were filled with warped reflections of themselves, neither beasts nor proper people.

The fearsome Neuers were wolves in summer and humans in winter. The Phanesians had massive ears, which they used as blankets and pillows. The Ichthyophagi of India were totally covered in hairy bristles and lived in rivers and streams. But a few groups were mentioned particularly often, and they were some of the strangest.

This map of the world is based on Herodotus’ writings. It is not terribly accurate.

Blemmyae

These were first described by Herodotus, who called them akephaloi, meaning “headless ones.” He claimed they lived in Eastern Libya. Other Greek sources called them sternophthalmoi, or “chest-eyed.” But they were later and better known as Blemmyae.

The Blemmyae, as their original names suggest, had no heads. Instead, their large faces were on their chests, shoulders, or stomachs. According to Roman writer Pliny the Elder, they lived in the ancient North African territory of Aethiopia, and were widely attested.

The curious chest-eyed people were popular in the Middle Ages as well. The 7th-century writer Isidore of Seville placed the Blemmyae in Libya. According to Isidore, there were two types of Blemmyae. Some, who were born as headless trunks, had their features on their chests. The others were born without a neck, and so their eyes were on their shoulders. What the practical difference is between those two things, he did not clarify.

The chronicler Bartholomaeus, writing in 1230, also includes Blemmyae, seemingly unsure what to make of them. Hedging his bets, he included them twice, once in the “animals” category and again in “peoples.”

Cartographers frequently included Blemmyae on maps, as border illustrations or on distant lands. The Hereford Mappa Mundi, a massive early 14th-century map in the Hereford Cathedral, shows a shield and spear-wielding Blemmyae in Abyssinia (modern-day Ethiopia).

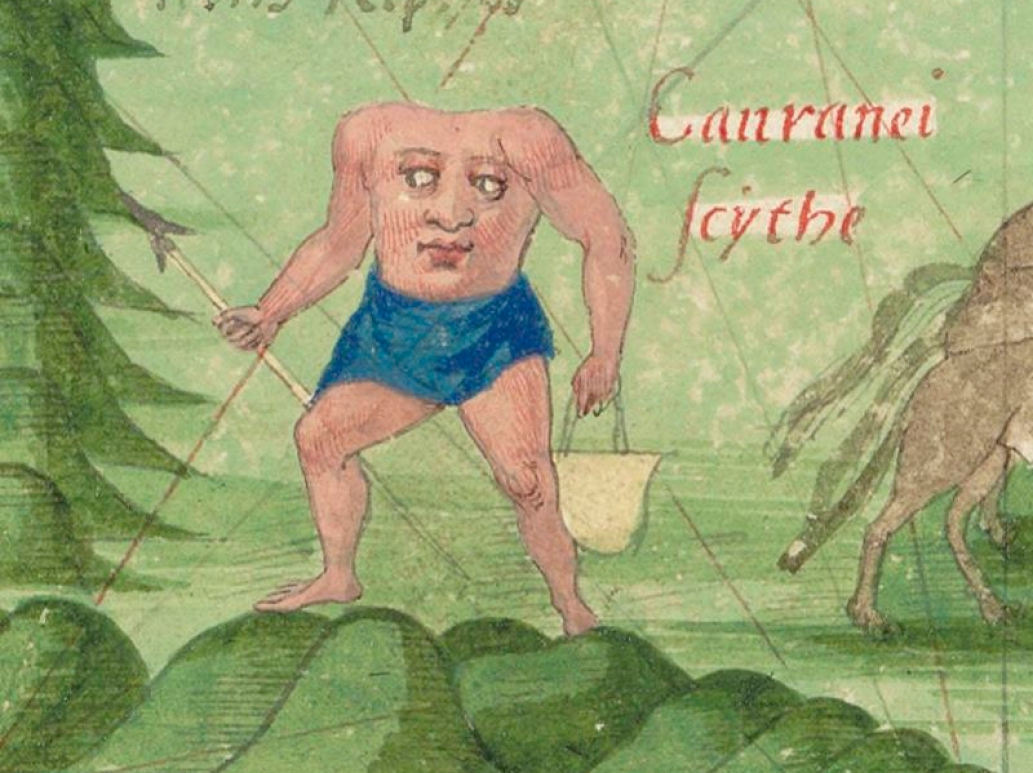

One of the many strange creatures populating Classical, Medieval, and Early Modern maps. From a 1556 map by Guillaume Le Testu. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Different continents, same headless people

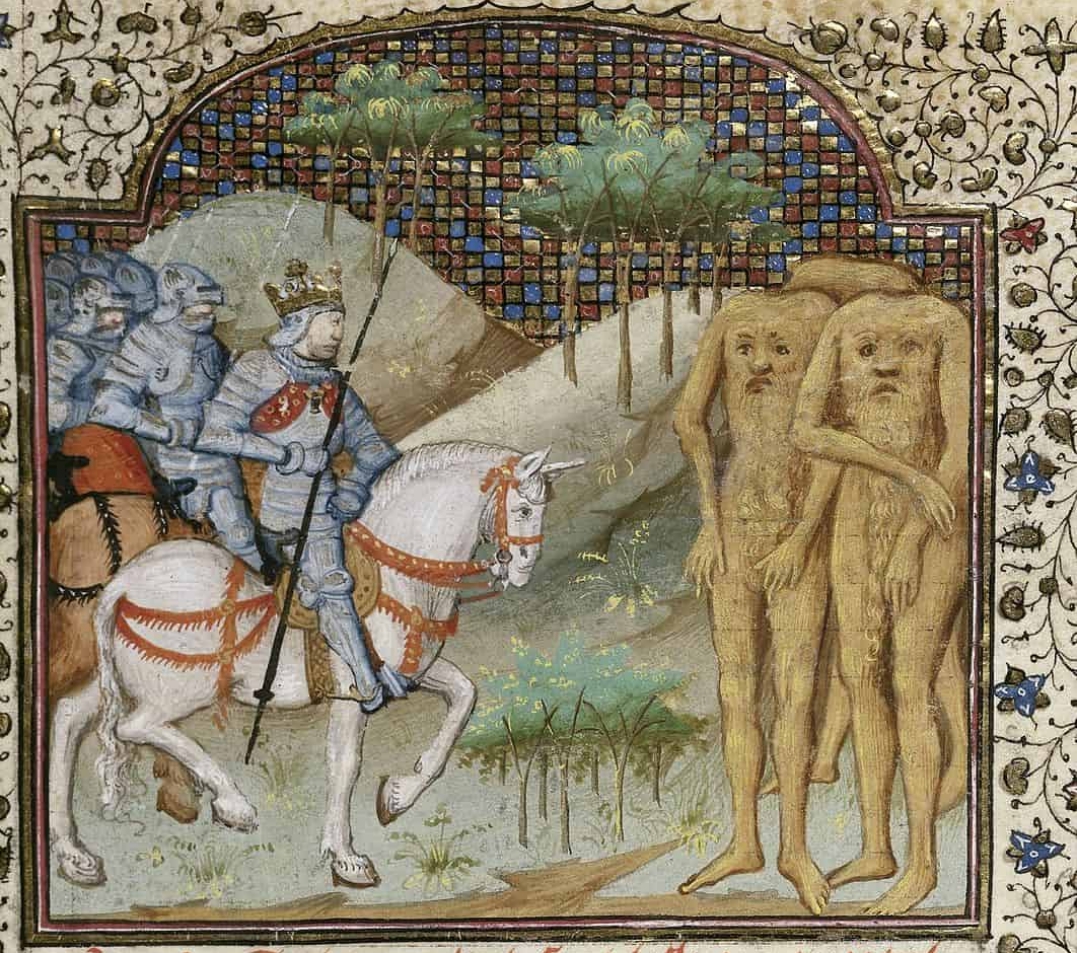

By the later 14th century, the Blemmyae were starting to appear outside of Africa. Mandeville’s Travels, a mostly fantastical travelog by the probably fictional Sir John Mandeville, reports that the Blemmyae live on an island somewhere in Asia. His impression of them is distinctly negative, calling them “of foul stature and of cursed kind.”

From there, the Blemmyae apparently emigrated to South America. In 1513, Ottoman admiral and explorer Piri Reis included them on his world map, near the coast of Brazil. According to his notes, they grew to about 5’3″, with close-set eyes, and were fairly harmless.

Famed (and real — here’s looking at you, Mandeville) English explorer Sir Walter Raleigh was convinced by reports he’d heard on his travels that the headless men existed. They were called Ewaipanoma, and they had “their eyes in their shoulders and their mouths in the middle of their breasts.” He didn’t see them himself, but “every child” of Guyana knew about them, so he believed it.

Hundreds of years later, European writers proposed that maybe the sightings of Blemmyae were really sightings of apes, like chimpanzees or Bonobos, who can look like people with faces on their chests if you really squint and, I guess, haven’t seen an ape before.

Ape or not, the Blemmyae made a mark on literary history, appearing in not one but two Shakespeare plays. The titular Othello claims to have seen “men whose heads/Do grow beneath their shoulders,” while in The Tempest, Gonzalo says that when he was a boy, he believed in “such men whose heads stood in their breasts.”

The Piri Reis map shows a Blemmyae as well as several other strange humanoid figures. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Cynocephali

While the Blemmyae had no heads at all, another purported race had the heads of dogs. The Cynocephali, or “dog-headed” people, first appeared in Ancient Greek writing. Fifth-century BCE physician Ctesias of Cnidus wrote that a tribe of dog-headed men lived in the mountains of India.

They wore animal skins and communicated with each other by barking, though they could understand the local language. The local Indians called them Calystrii and said they sent annual offerings of fruits, flowers, and amber to the King of India. In exchange, he sent them bows, swords, and other weapons.

The Calystrii were 120,000 strong and undefeatable in war but lived very simple lives. Instead of beds, they slept on leaves or grass, bathed rarely, and lived off raw meat. The lifestyle evidently agreed with them, because they could live up to 200 years.

According to Pliny the Elder, however, the Cynocephali were livestock kept by the Menismini people, a nomadic Aethopian tribe. The Menismini lived off the milk of Cynocephali, which they kept in vast herds of females, culling most of the males.

This image from the 15th-century Nuremberg Chronicle is often mislabeled as a werewolf. It’s actually a Cynocephalus. Photo: University of Cambridge Digital Library

Man or beast?

Medieval depictions lean much closer to the earlier interpretation. The Liber Monstrum, a book of monsters found in the same manuscript as Beowulf, places the Cynocephali in India. They didn’t speak, only bark, and lived off of raw flesh like animals do.

But other writers considered them more human-like than bestial. Odoric of Pordeno, a 13th-century Franciscan monk and world traveler, claimed to have encountered the Cynocephali on the island of Nicoveran. Now known to be one of the Nicobar Islands of the Indian Ocean, Odoric claimed it was home to a sophisticated dog-man society. The Nicoverans had organized religion — they worshipped an ox, and wore ox-shaped gold and silver emblems on their foreheads — and had a king who ruled well and justly, so that it was safe to travel his kingdom.

Marco Polo had quite a different impression of his dog-head-inhabited island. On the Angamanain Island (Adaman Islands) in the Bay of Biscay, he described a people with no king, who had heads like dogs. While the island was rich in spices, the people were beast-like and ate outsiders. Cannibalism is frequently mentioned in connection with dog-human hybrids.

Early modern explorers didn’t seem to encounter any Cynocephali in the New World, but they were pretty sure they were there. Christopher Columbus claimed that natives had told him about a group of cannibals who had the faces of dogs. The Piri Reis map, following Columbus’ claims, affixes a trio of dog men to the coast of South America.

The well-dressed Cynocephali of Nicobar. Photo: Odoric of Pordeno, ‘Livre des Merveilles’ Bibliothèque Nationale de France online archive

Sciapods

One of the more absurd Monstrous Peoples was the Sciapods. Ctesias of Cnidus placed them in India alongside the Blemmyae and Cynocephali. Instead of a pair of legs, the Sciapods had one large leg and foot. This giant foot was quite useful, allowing them to hop along faster than any two-legged creature. It could also be a sunshade or umbrella, and they would sleep with their foot held up over themselves to keep out rain or sun.

This habit gave them their name Sciapod, meaning “shade-foot.” They were also called Monopod, or “one-foot.” These rather whimsical people were well known in the ancient world, even appearing in Aristophanes’ celebrated comedy play, The Birds, which debuted in 414 BCE. Pliny the Elder includes them in his Natural History, an exhaustive 39-volume encyclopedia.

Sciapods continued to be popular in the Middle Ages. In the Liber Monstrum, they are again described as moving very quickly and using their feet for shade. The book goes on to explain that their knees harden into an inflexible joint, making one wonder how they are jumping at all.

They appeared frequently as decorative motifs, as marginalia in illuminated manuscripts, on the borders of maps, and even carved into the walls of cathedrals.

But they stretched the boundaries of belief, even in a time when those boundaries were extremely flexible. Fourteenth-century writer Giovanni de Marignolli, who traveled to India and China, argued that occasional one-footed men may exist but that they were not an entire race. Instead, he says, earlier writers were seeing chatra, an umbrella-like device carried as part of royal regalia in India.

A Sciapod holding his foot over his head to block the sun, from the Nuremberg Chronicle. Photo: University of Cambridge Digital Library

The point of monsters

You probably noticed that around the 16th century, something curious happened: The monstrous peoples moved continents. When an area became familiar, as trade routes opened and maps were filled in, the monsters moved to a new borderland. When early modern explorers reached the New World, they used the familiar images and stories of monstrous foreigners to understand their interactions with Indigenous people.

Famous Christian theologian Augustine of Hippo wrestled with the question of whether monstrous peoples like the Cynocephali and Sciapods were human or animal. He decides that no matter their appearance, if they are rational, then they are human, possess souls, and are descended from Adam.

But early modern explorers weren’t so convinced. The notes on the borders of the Piri Reis map claimed the inhabitants of the New World, depicted as Blemmyae and Cynocephali, were like animals, not like people.

Depicting foreign people as monsters allowed Classical and later Medieval people to reassure themselves of their own superiority. They imagined themselves in contrast to “monstrous, uncivilized races” in Africa, India, and China. Establishing this contrast was even more important for explorers in the New World. If the people there weren’t people at all but monsters, then it was all right to kill, enslave, and exploit them.

Eventually, the idea that foreign people were physically, literally monsters faded from the popular imagination. The fear and prejudice behind that idea, however, still haunts us today.