During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, denizens of the Old West reported seeing a strange and mysterious beast: the camel. These sightings were not the fevered hallucinations of cowboys experiencing heatstroke, dehydration, whiskey, or tuberculosis. There really was a population of feral camels wandering the Sonoran Desert.

How did a bunch of camels end up loose in the desert? The U.S. Army, of course.

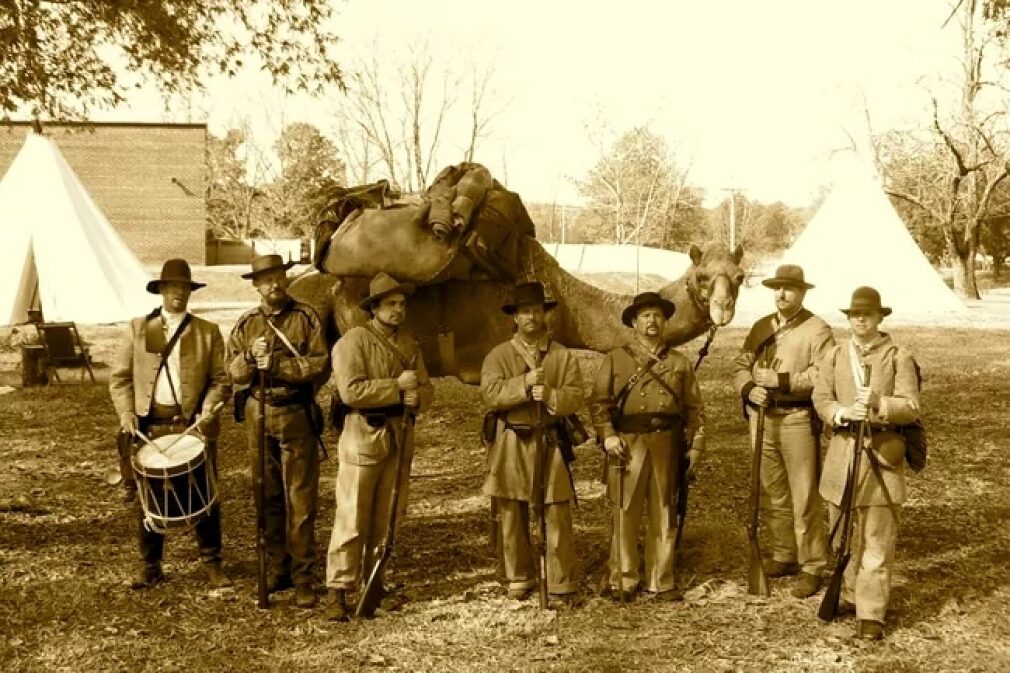

This illustration of an American soldier with two camels, one Bactrian (two-humped) and the other dromedary (one-humped) shows their intimidating size. Photo: Harpers Weekly

A quartermaster dreams of camels

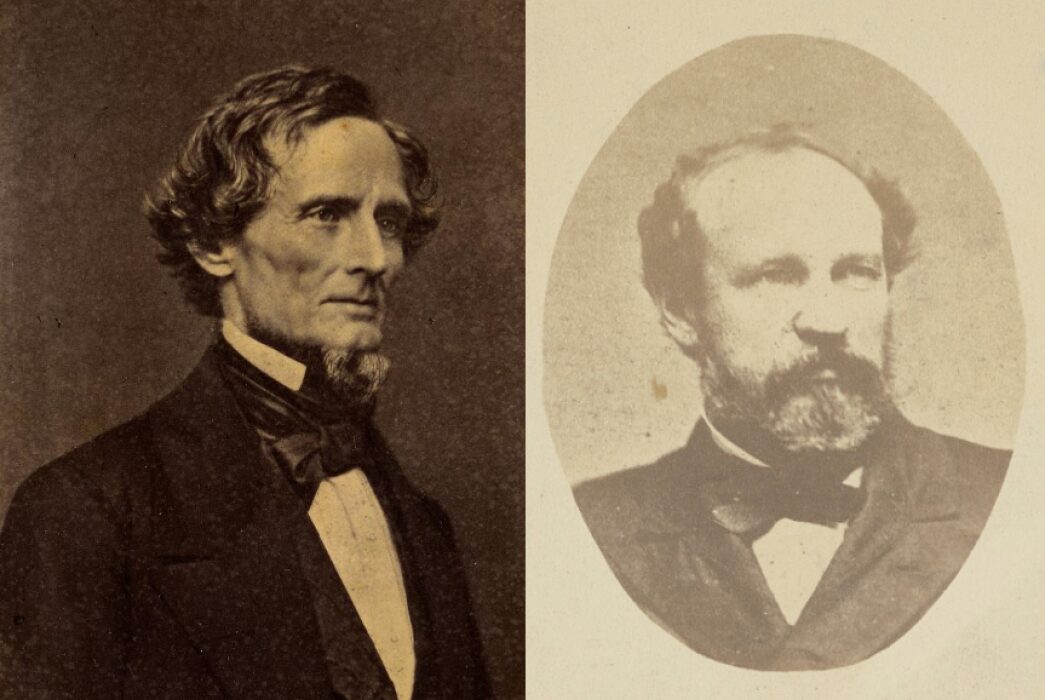

The two visionaries met during the Mexican-American War. Henry Constantine Wayne was a Georgia native in his early thirties, a former West Point instructor decorated for his bravery in the battles of Contreras and Churubusco. The Pennsylvanian George Crosman was older, almost fifty, and saw little active combat. He was a logistics man with camel-related ambitions.

In 1836, Crosman had presented a proposal to the higher-ups in the War Department, advocating a U.S. Army Camel Core. They were unreceptive. A decade later, however, Henry Wayne was listening. Wayne wrote his own report for the War Department, and this time it ended up on the desk of a fellow West Point alumnus: Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis. He was interested.

George H. Crosman would probably be known as ‘The Father of the American Camel’ if the American camel had worked out. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The U.S. Army Camel Corps

At the time, the issue of slavery dominated American cultural and political debate. Specifically, the expansion of slavery. As the U.S. carved more and more territory from Mexico and various Indigenous nations, they would have to decide whether brand-new states would hold slaves or not.

With every new territory came a race to move as many slave-holding settlers (and their slaves) into the area. If they could get a significant enough voting block together, then the territory could be a slave state once it attained statehood.

Davis, a Southern plantation owner and, jumping ahead here, future President of the Confederacy, was extremely pro-expanding slavery. The corresponding drive to Manifest Destiny convinced him there was an urgent need to forge paths through the desert. And he thought camels would help him do it.

After half a decade, Congress finally agreed to let him try out the camels. Congress gave Davis, now Secretary of War, $30,000 for camels. Major Henry C. Davis appointed Wayne as head of the project immediately.

Two men brought together by a mutual enthusiasm for both camels and the institution of slavery. Right, Henry C. Wayne, Left, Jefferson Davis. Photo: Library of Congress

The Cape Verde camel camp

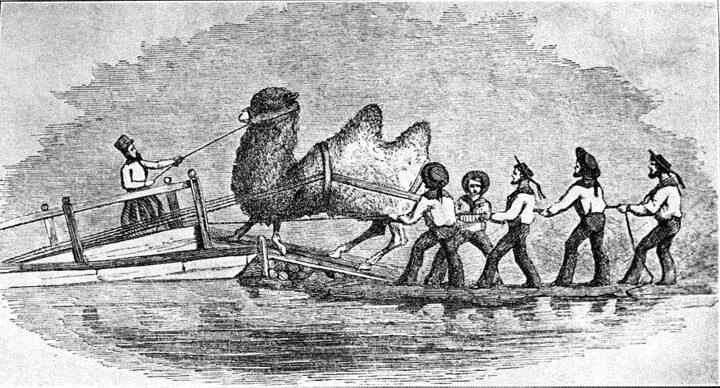

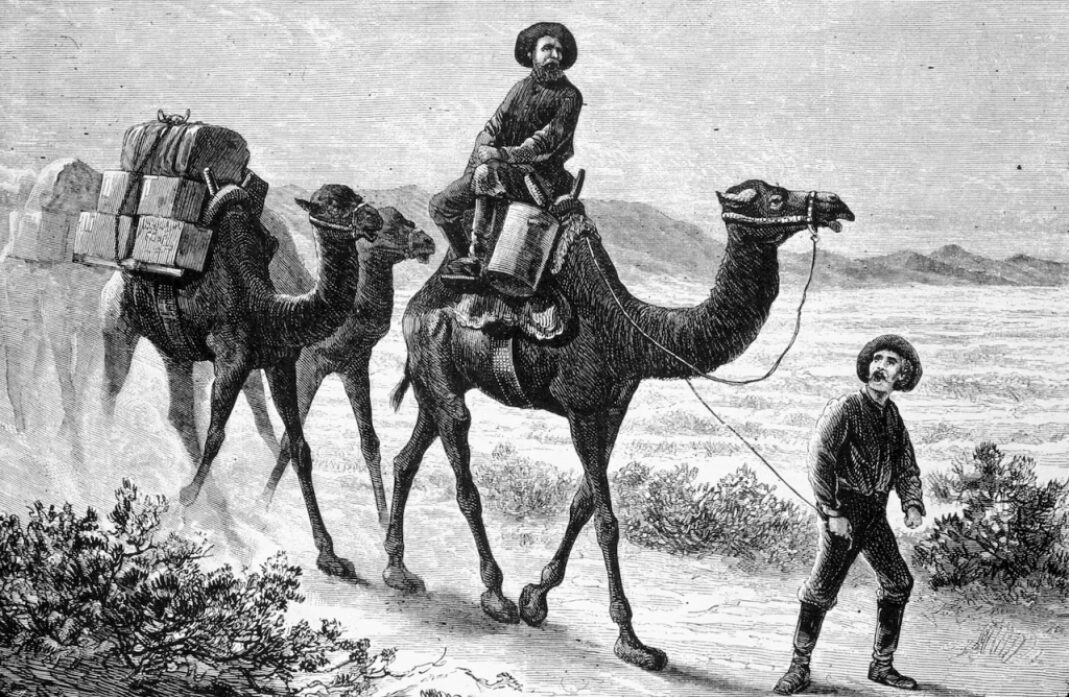

Wayne sent the USS Supply, commanded by David Dixon Porter, to buy as many camels as he could fit in the ship. Porter’s father was a diplomat who had taken his son along on trips to the Middle East, so was qualified for the position in that he had seen camels before. He fitted the ship with custom-made harness and ventilation systems and loaded up 33 camels and five Arab and Turkish drivers.

The modifications to the Supply did their job, and the ship duly landed in Texas was 34 camels aboard. One had died, but two calves had been born. The trip had gone so well and so cheaply — they still had $22,000 left — that Wayne sent Palmer right back to Egypt for a second load. Six months later, in early 1857, Palmer delivered another 41 camels to Texas.

Wayne took the camels, the hired drivers, and a (likely somewhat confused) herd of army soldiers and marched them over 190km to San Antonio. He then moved them another 90km to Camp Verde, where he established a more permanent camel facility.

Experiments with camels

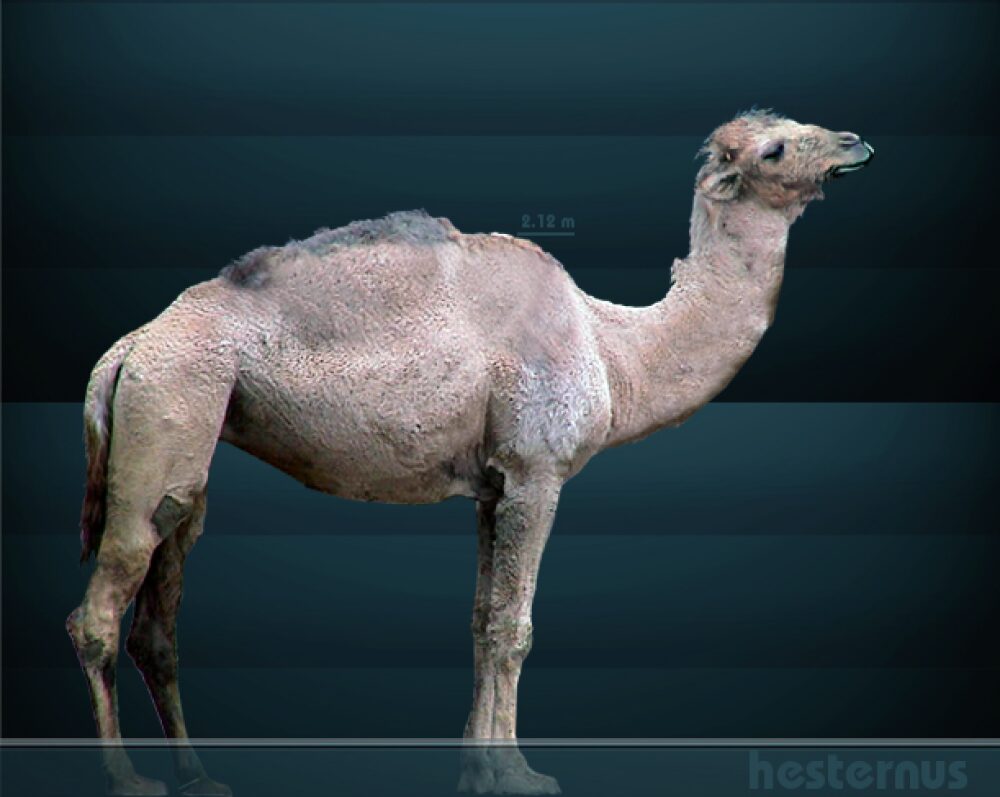

It wasn’t entirely off-base to think camels might do well in the American Southwest. Camels are sturdy, heat and drought-resistant, and incredibly tough. In fact, a now-extinct camel ancestor, the Camelops, lived all across the region during the Pleistocene era. The species had been discovered and named only three years before Wayne began experimenting at Cape Verde.

A recreation of the ancient camel ancestor which lived in the American Southwest. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

On the trail, the experiment seemed to pay off. The camels could go without water for over a week and were content living off scrub grass. The heat didn’t bother them, and they faced the hardships of the trail with placid indifference.

There were some hiccups. Soldiers were used to constantly whipping their mules and horses, but camels don’t put up with mistreatment. The men were unpleasantly surprised when their desert steeds responded with terrible violence and jets of cud. The smell of camels was also a frequent complaint. But their performance was undeniable.

In one test, comparing a team of six camels with a similar team of mules, the camel team was able to transport twice the amount of goods in half the time. Wayne was thrilled, writing that the results of the camel trials were “as favorable as the most sanguine could have hoped.”

A new administration began in March of 1857, and both Davis and Wayne were out of their old jobs and off the camel division. But after investing so much money and time, the military wasn’t ready to give up.

This photo, taken at Drum Barracks, San Pedro, California, is the only known photo of a U.S. Army camel, foreground, in active service. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Beale’s Wagon Road

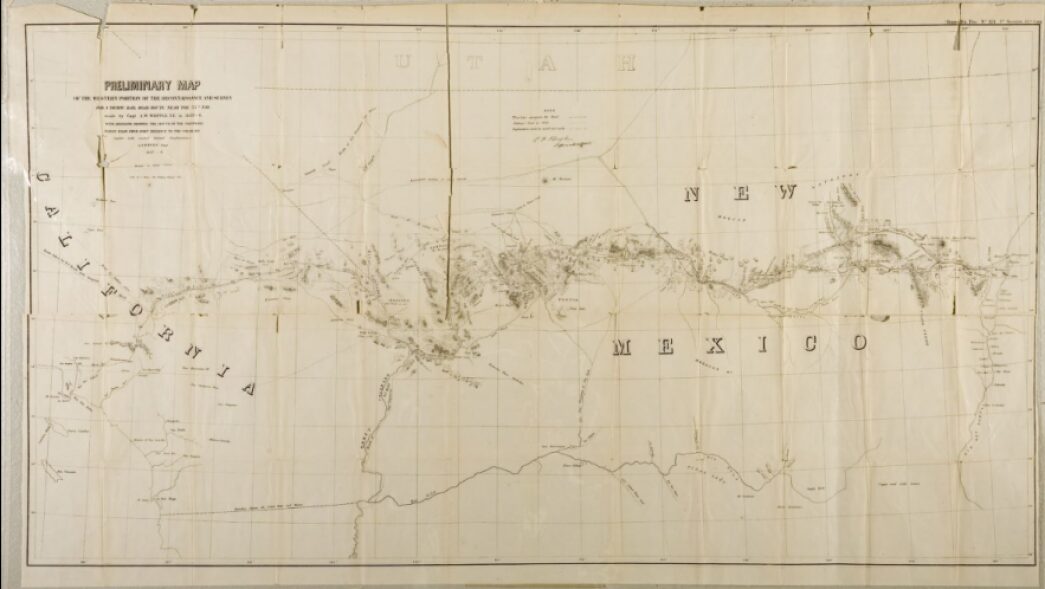

As in any good Western film, the railroad was coming to town. Eventually. First, Congress needed someone to survey the route between Fort Defiance and the Colorado River. The man who won the contract was Edward Fitzgerald Beale, a wealthy frontiersman and former California Superintendent of Indian Affairs. His previous claim to fame was starting the Gold Rush by bringing the first Californian gold nuggets back East.

It was only once he had already signed the paperwork that the Secretary of War, Columbo-esque, said there was just…one more thing:

He was going to have to use camels. Despite Beale’s repeated and strongly worded protests, he was given 25 camels. They set out in June of 1857, surely an ideal time of year to cross vast deserts.

At first, the camels lagged behind. The lead camel driver was patient, though, slowly conditioning the animals to haul heavy loads. He was a Syrian-Greek Muslim convert named Hadji Ali, which the American soldiers bastardized as “Hi Jolly.”

Under Hadji Ali, the camels found their footing, and Beale was soon grateful to have them. They began outpacing the horses and mules, even carrying 300 kg. After months of hauling heavy supplies, not only had no camels died, but they were as healthy as when they had left. Beale was a camel convert, saying that “there never was anything so patient or enduring and so little troublesome as this noble animal.”

After the success of this venture, Beale took camels on another expedition, this one over a year long. Again, they performed terrifically. His report to Congress strongly urged further investment in the camel. They weren’t interested.

Beale’s map charting the route they took during the expedition. Photo: Northern Arizona University Library

Texas wants camels

While Beale was forging his wagon trail, Henry Wayne was still enthusiastic about camels. He published a letter in an 1858 edition of the National Intelligencer, extolling the virtues of camels as pack and work animals. In addition to being strong and hardy, he claimed, they were docile enough that enslaved people could handle and manage them.

His article was reprinted and read across the South, and private Southern plantation owners rushed to import camels of their own.

There was another benefit that importing camels brought to slave owners. The U.S. had banned the importing of slaves in 1808, but that didn’t stop demand. Slave ships, however, were easy to spot. The characteristic large water tanks, excess food supplies and the stench of death and excrement gave away the game to patrolling British warships. But camels were the perfect cover, requiring food and water tanks and producing strong odors, and being brought from West Africa to the Southern United States.

Mere months after Wayne’s article was published, the Thomas Watson docked in Galveston and publicly unloaded 89 camels. Federal officials suspected it was secretly a slave ship but didn’t feel there was enough evidence to investigate further. Meanwhile, the camels were released into the town, causing havoc. Three years later, authorities caught the owner of the Thomas Watson, John A. Machado, smuggling slaves into the U.S.

Loading a reluctant camel onto a ship for export to the United States. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Brother against brother against camel

The mule lobby, worried that the sturdier, hardier camels would ruin them, pressured Congress to end the camel experiment. But the main reason Congress wasn’t interested in Beale’s camel report was that they were very busy at the moment. Half of the country was seceding. The outbreak of the Civil War ended the American camel experiment. Those camels already in the country were caught between the two sides.

Many privately owned camels were set loose in the desert as mining and farming operations ground to a halt.

Cape Verde was captured by Confederate forces in 1861. The Confederates put some of them to work transporting supplies but treated the animals poorly, and many died. One was even pushed off a cliff by its new owners. A standout, “Old Douglas,” became the mascot of the 43rd Mississippi and was killed by a Union sharpshooter at Vicksburg.

The Fort Tejon herd remained in Union hands and fared better. They were kept in good condition, transferred from station to station, as officials tried to think of something to do with them. After three years, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered them sold off. When the war ended, those who had survived their time with the Confederacy were also sold, for only $31 per animal.

Old friends and camel fans Henry Wayne and George Crosman ended up fighting on opposite sides. Confederate inspector-general Wayne’s most relevant action was failing to stop Union forces from crossing the Oconee River in his home state of Georgia. Crosman, then in his late sixties, was recognized for his dedicated service as the Chief Quartermaster for Pennsylvania.

“Old Douglas” with the 43rd Mississippi. According to some reports, they ate him after his death. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Circuses and creosote

After the war, the old camels were scattered across the frontier. Many ended up in circuses and zoos, while others were put to hard labor in mines. Edward Beale, still fond of the animals, bought some for his ranch. Bored Western townspeople started holding camel races with rounded-up animals.

Eventually, most of them were turned loose to fend for themselves. Camels are pretty good at that, and they can easily live into their fifties. They formed small herds, interbreeding and happily eating the creosote bush that few other animals would touch. Their ancestors, the Camelops, had once fed on the same plant.

After the experiment ended, many of the old camels went to work in the mining industry. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The legend of Hi Jolly

Hadji Ali kept two of the old army animals, Maya and Toulli, who helped pull his wagons. He had turned to prospecting, but he still did a fair bit of camel wrangling when required. With so many camels roaming around, it was sometimes required. In 1873, Ali led over seventy camels through the streets of Tucson, Arizona to a mining operation in Colorado.

He settled in Tucson for a time, marrying and having two daughters. But he still dreamed of digging up gold and left for the remote settlement of Quartzsite, Arizona. There, locals reported he would be called in to deal with feral camels from time to time. He mostly failed at prospecting but became a beloved local character, living off charity.

Hadji Ali (Hi Jolly) as an old man and prospector in Quartzsite, Arizona. Photo: Arizona Memory Project

An early Arizona congressman, Mark Smith, tried to help Ali, appealing to the government for a pension. After all, Ali had served in the U.S. Army across various projects for almost thirty years. But he wasn’t officially on the books, and they said no.

In late 1902, he died destitute. But the small town of Quartzsite didn’t forget him. Over thirty years later, the Arizona State Highway Department erected a monument over his plain wooden grave marker. The stone pyramid, topped with a camel-shaped weathervane, is still there today.

Left, the tomb of ‘Hi Jolly’ in Quartzite. Right, Hadji Ali and his wife, Gertrudis Serna, in Tucson, Arizona. Photo: Arizona Memory Project

Strange sightings

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, encounters with camels trickled in, mostly from prospectors and cowboy-types. Here are only a few of the many stories, most of which are vague and impossible to verify.

1875, an old army camel wandered into Bandera, Texas and was captured by a fellow Camel Corps veteran.

The future General Douglas MacArthur remembered seeing one as a small child in 1885, “one of the old army camels,” wandering outside the garrison at Fort Seldon, New Mexico.

The International Boundary Commission, on an 1887 surveying project to establish the Mexico-U.S. border, saw a pair of camels. They were looking healthy, living about 60 kilometers from the border.

In 1907, a prospector reported seeing a pair of them in the wilds of Nevada.

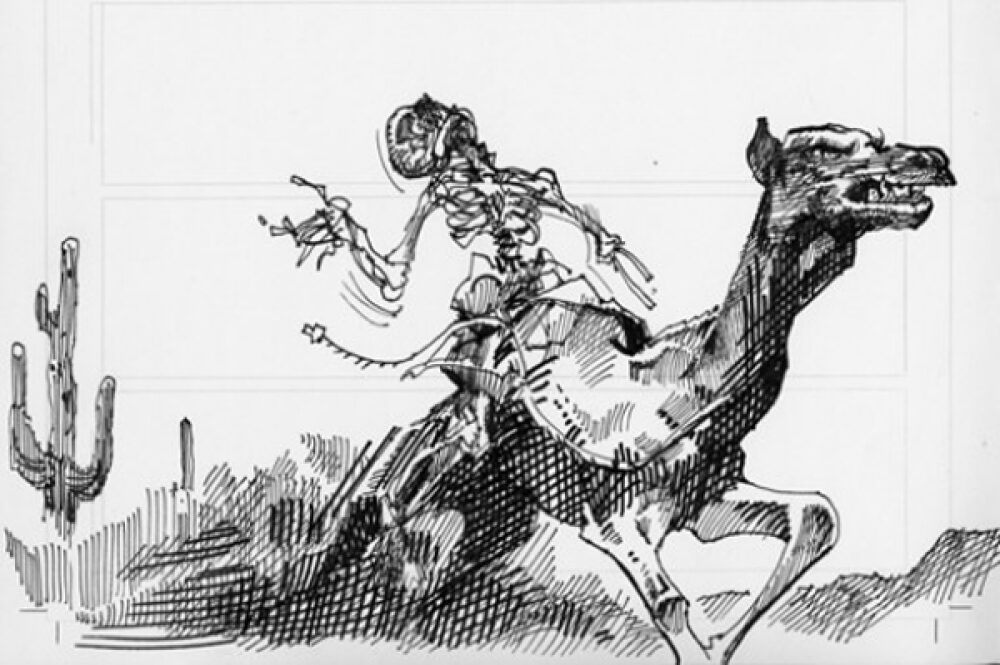

The Red Ghost

The most famous and spectacular camel sighting was of the Red Ghost.

Sighting is probably too gentle a word. Encounter might be better. According to contemporary 1883 newspaper reports, the wild camel was out of control, knocking a woman over and trampling her to death.

Weeks later, a nearby group of miners had their camp destroyed by a large, red creature. After a third sighting, a well-respected local hunter named Cyrus (sometimes Si) Hamlin identified it as a camel. A camel which seemed to have something strapped to its back.

The same year, a group of hunters in the Verde Valley, less than 100 km away, saw it again. A large, red camel with something tied to it. They got closer and fired a few shots, which scared it away. But when it bolted, something fell off, coming to rest on the dry-baked earth.

It was a withered human head.

Years later, a cowboy saw it in an abandoned corral east of Phoenix. He, too, believed he saw a corpse tied to the camel.

The reign of the Red Ghost ended in 1893. A farmer named Mizoo Hastings caught the beast eating his turnips and promptly opened fire. When he examined the body, he found deep scars which looked to have been left by leather straps.

The ‘Red Ghost’ was sometimes described as a malicious, even supernatural force. In other tellings, it was simply an old and abandoned beast of burden driven mad by pain and years of lonely wandering. Photo: True West Magazine Archives

Who was the man tied to a camel?

Many theories and tales of the Red Ghost have been passed around since then. As a kid in Southern Arizona, I heard that the man was a prospector who got lost in the desert. He either owned or had caught a camel. Feeling himself grow weak from thirst, he strapped himself to the beast, hoping it would take him to water. Camels need to drink far less frequently than prospectors do, so the unfortunate fellow died before his camel grew thirsty.

Another theory is that it was an Army prank gone wrong. A soldier was jokingly tied to one of the captured camels by his laughing comrades. The camel bolted, though, running off into the desert.

More supernaturally-minded people might call the beast a vengeful ghost. The angry spirit of hundreds of camels brought far from their homes to toil and which then were abandoned.

Is there any truth to the Red Ghost? Sightings really were reported in newspapers. Camels really were out there in the desert. The Red Ghost occupies the place of all good folklore: It lives in the realm of plausibility.

This statue in honor of the Red Ghost stands in Quartzsite and is called Georgette. Photo: Atlas Obscura

Are they still out there?

As late as 1929, there were reports of a wild camel frightening a herd of horses in Banning, California. But the days of the wild American camel were ending.

In 1934, “Topsy” died in Los Angeles’ Griffith Park Zoo. She had wandered alone from Arizona into Los Angeles, where she found a home until her death.

The remains of ‘Topsy’ are regularly loaned out by the Natural History Museum of LA County so she can serve as a teaching and learning tool. Her skeleton bears the marks of a long and eventful life. Photo: Natural History Museum of LA County

Sightings continued, of course, though they were less credible. Even today, over 150 years since the camels arrived, some believe there are wild populations alive out there. I have personally met people who swore to have seen a camel out in the desert.

My heart says yes. Experts say no. There wasn’t a large enough breeding population to sustain wild American camels beyond two or three generations. There hasn’t been a confirmed sighting in over a hundred years. The legacy of the feral American camel, however, remains.

The wagon road that camels helped build never became a railroad line. It did become Route 66, though.