As the climate warms, the dangers on glaciers and steep, snowy mountains increase. What will this mean to the future of climbing on Everest?

Recently, the BBC reported that Nepal is preparing to move Everest Base Camp down the valley. Its current location, on the thinning Khumbu Glacier, is becoming too dangerous. And there are other problems.

The void beneath

Nepal’s Department of Tourism are currently studying the alternative location, 200 to 400m lower down, on solid ground.

So far, the canvas town that is Everest base Camp spreads over rough glacier terrain, amid ice, rocks, bumps, cracks, and shallow holes that turn into ponds on sunny days, then freeze up again at night.

The location is no minor question since Everest Base Camp usually hosts around 1,500 people. In addition, a lower start would severely affect the expeditions’ tactics and logistics.

The Khumbu Icefall and Everest Base Camp. Photo: Furtenbach Adventures

Icefall shakes more than ever

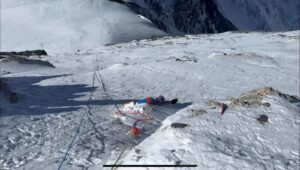

As the Khumbu Glacier thins, the Icefall between Base Camp and Camp 1 becomes more unstable. As the BBC reported, higher temperatures create weaker snow bridges among crevasses, and crevasses appear more often. Some climbers fear that a crevasse might open up beneath them as they sleep in their tents.

Taranath Adhikari, director-general of Nepal’s tourism department, hinted to the BBC that the move could take place in 2024.

Nivesh Karki of Pioneer Adventure confirmed to ExplorersWeb that no decision has been made yet. The outfitter says that local climbers tell him that the Khumbu Icefall seems to be “shaking more” this year than previously. Nevertheless, the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC) believes that the route through the Icefall will be safe “for a few more years”.

The Khumbu Icefall. Photo: Furtenbach Adventures

Among other things, the SPCC hires the Ice Doctors who open and maintain the route through the Khumbu Icefall to C1 on the Western Cwm every season. But according to the BBC, the SPCC has only ensured that the Icefall will be available for three or four more years, which is really not much.

Moving — but where?

“Not sure where they’re proposing to put [Base Camp],” British guide Tim Mosedale wrote recently. “But it will undoubtedly [take much longer] to get to C1 and C2…not only for climbers but also for the Sherpa staff who undertake the journey a dozen or more times a season.

“Some climbers take 14 to 20 hours to do their second rotation from EBC to C2, so there are significant repercussions if the journey is extended much longer,” Mosedale added.

The Ice Doctors on their way through the Khumbu Icefall. Photo: SPCC

Uncertain alternatives

“If EBC is moved, it wouldn’t surprise me if an Advanced Base Camp is established at around 5,350m, just at the bottom of the Khumbu Icefall,” Mosedale said.

Alternately, climbers could change strategy and acclimatize first on trekking peaks, then move all the way to Camps 1 or 2 to await their summit push. Helicopters would be used to better supply the camps on the Western Cwm and the Valley of Silence, and to airlift workers (camp crew, guides, and rope fixers).

Helicopters are only supposed to carry supplies and workers and evacuate sick or injured climbers. But on some occasions, they have reportedly shuttled to C1 rich clients who wanted to avoid the perils of the Icefall.

However, there are serious downsides to creating a new ABC. As it is, Everest can barely maintain its current number of visitors. All the overcrowding and environmental impact would simply migrate up the glacier, to even more fragile areas. The increasingly complex waste management, the luxuries that teams have grown used to, the huge camps…

At 6,400m, this would be far more than the mountain could endure. It could lead to a radically diminished number of permits. Logistics might return to minimalistic.

A helicopter lands at Everest BC. Photo by @jessica.amity, Heli Everest

Whatever happens, helicopters shouldn’t be an option for the climbers themselves, if they still want to be called by that name. A complete Everest climb must begin at the base of the mountain, not midway, so there would be no point in starting from 6,400m.

Besides, the top of the Icefall is not the end of the bad news.

Good weather, bad news

The 2022 season featured an extraordinarily long period of excellent weather. This gave everyone on the mountain a chance to summit and led to a high percentage of success. Yet this might not be all good news, once we consider climate change.

Kilian Jornet at 6,100m on Everest two years ago, showing how much hotter it’s become up there. Photo: Kilian Jornet

High temperatures often increase the objective difficulties and risks on the highest peaks, especially on Everest.

“It is concerning for the future,” Lukas Furtenbach told ExplorersWeb. Besides an Everest outfitter, Furtenbach is also a geographer, specializing in gravitational processes, climate change, and risk management of natural hazards at the University of Innsbruck.

Lukas Furtenbach.

Challenges ahead

“Exceptional warm temperatures with melting water (!) at the South Col and the absence of the jet stream show the speed and extent of the effects of global warming on the highest mountains,” he told ExplorersWeb. “We will face completely new challenges climbing Everest in the near future.”

He listed some future effects of climate change on Everest:

- The Khumbu Icefall will become more unstable, and move faster, with more gravity- and temperature-triggered events.

- More avalanches from Nuptse and Everest’s West Shoulder can reach both the climbing route and Camps 1 and 2.

- More and larger crevasses in the Western Cwm and on the Lhotse Face.

- The whole Southeast Ridge and summit ridge could become unstable, with more crevasses on the ridge and on the lower glacier leading to the Balcony. All the rocky sections will become more unstable.

- More cyclones in the Bay of Bengal because of more heat (energy) in the atmosphere. This means more cyclones hitting Everest, bringing heavy snowfall. This in turn leads to more avalanches because of the warm temperatures.

Everest climbers above Camp 4. Photo: Pioneer Adventure

The China option?

Some might argue that Everest’s overcrowding might decrease once China re-opens the north side to foreign expeditions and visitors distribute themselves on both sides of the mountain. However, it is yet unclear if, when, and most of all, how is China going to manage the access to their prized side of Everest. The crowding problem may only spread to the north side as well.

If current climate trends continue, scaling Everest will become more hazardous, more expensive, and more limited. This will affect not only those who dream of an Everest summit among their life accomplishments but also the thousands of families in Nepal who depend on income from tourism.