The world’s largest iceberg might be on a collision course for South Georgia Island. If it grounds on the continental shelf there, it could seriously disrupt wildlife and shipping in the area.

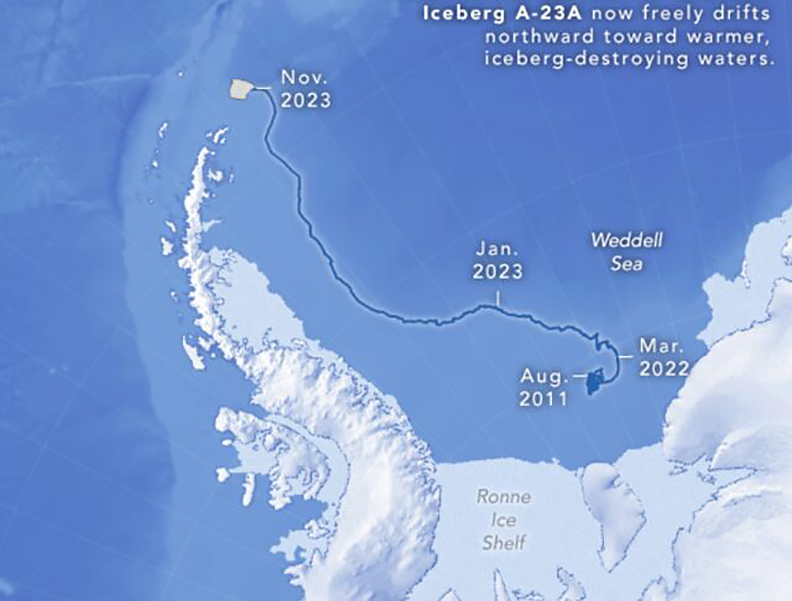

A23a broke off from Antarctica’s Filchner Ice Shelf in 1986. It hung around for decades in the Weddell Sea before it started to drift northward. Four years later, it became trapped in a swirling underwater vortex called a Taylor column. The mega-berg spent the months between May and December 2024 stuck in one spot, slowly rotating about 15 degrees daily. Then, just before the end of the year, it broke free and headed north again.

A23a has had quite an adventurous life since breaking off from an Antarctic ice shelf. It floated in the Weddell Sea for decades, got trapped in a whirlpool for months last year, broke free, and is now galloping toward South Georgia. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Now, it appears to be on track to smack into South Georgia Island, a British Overseas Territory. Currently, A23a is about 280km from the island.

South Georgia will be familiar to many fans of polar exploration. It’s the spot where Ernest Shackleton and five men landed after an incredible 1,300km open-boat journey while seeking rescue from the doomed Endurance expedition.

How to measure an iceberg

It’s hard to overstate just how large A23a is. While it’s lost about 400 square kilometers of its original 3,900 square kilometers, it’s roughly the size of one Rhode Island, 2.2 Londons, or 1.5 million Ernest Shackletons huddled shoulder to shoulder.

A23a’s walls reach as high as 400 meters, or 1,666 ship’s cats standing atop one another.

“Icebergs are inherently dangerous. I would be extraordinarily happy if it just completely missed us,” Simon Wallace, a local sea captain, told the BBC.

Wallace’s concern is legitimate. A23a has already started to deteriorate in the relatively warmer waters it now floats through. If it grounds onto South Georgia, it will continue breaking apart, filling the water with chunks as large as sports arenas. That will be a major hazard to the fishing vessels that navigate nearby. A23a could also have an ecological impact.

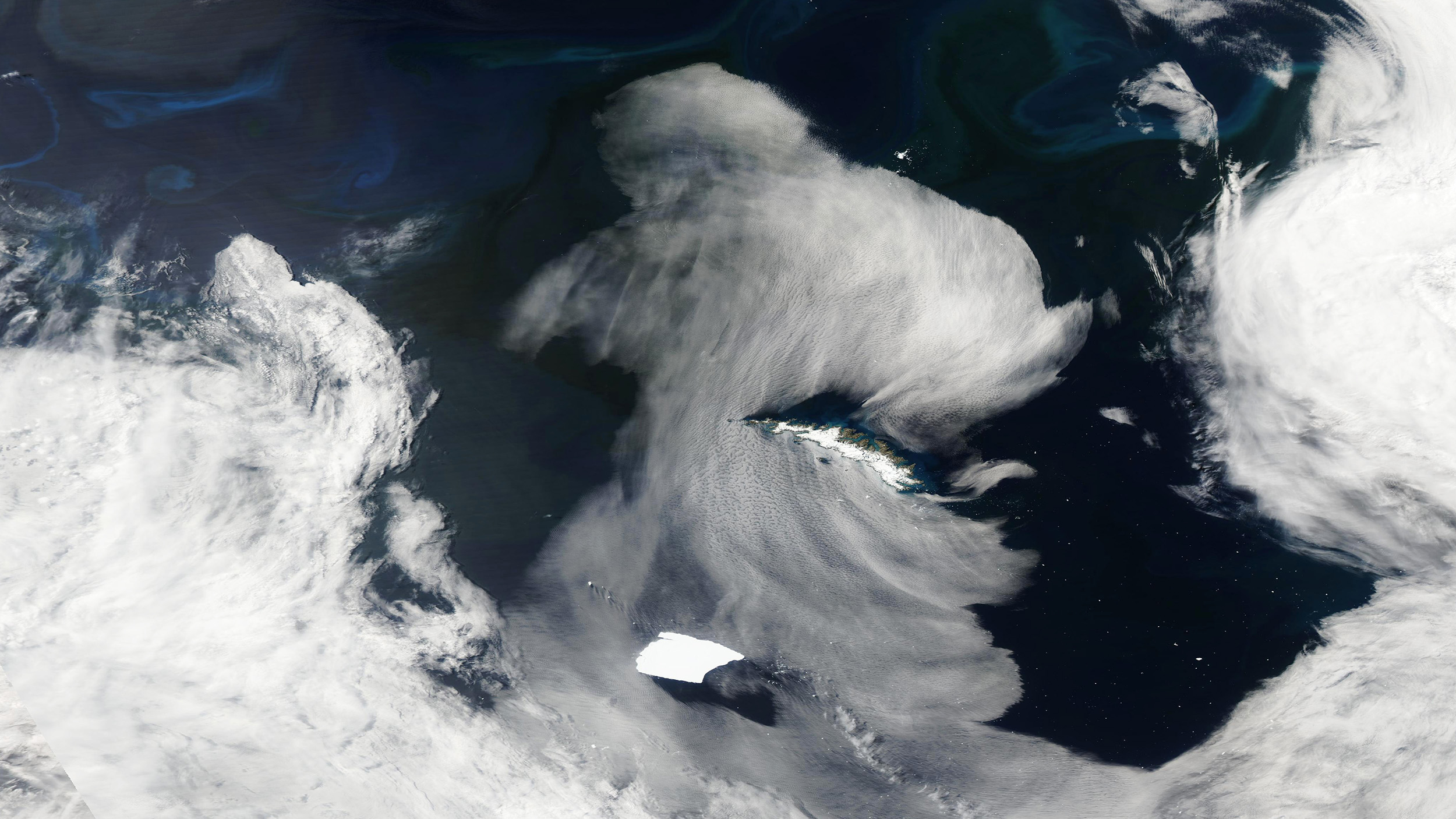

This image was taken when A23a was still 400km from South Georgia. It’s considerably closer now. Photo: Copernicus Sentinel-3

Capacity to adapt

Icebergs grounding on South Georgia Island are relatively common because of the island’s location. But the larger they are, the more catastrophic the potential.

“A close-in iceberg has massive implications for where land-based predators might be able to forage,” Professor Geraint Tarling, British Antarctic Survey (BAS), explained to the BBC in 2020.

“When you’re talking about penguins and seals during the period that’s really crucial to them — during pup and chick-rearing — the actual distance they have to travel to find food (fish and krill) really matters. If they have to do a big detour, it means they’re not going to get back to their young in time to prevent them from starving to death.”

The mega-berg could also damage and disturb organisms on the ocean floor. But it’s all part of the natural order, Mark Belchier, a marine ecologist who advises the South Georgian government, noted.

“South Georgia sits in Iceberg Alley, so impacts are to be expected for both fisheries and wildlife, and both have a great capacity to adapt,” he said.