Over the last 12 months, ExplorersWeb has documented incredible adventures in climbing, cycling, running, walking, skiing and anything involving force of will and dedication to a dream in the outdoors. As this year comes to a close, we present our countdown of the Top 10 Expeditions of 2019.

Early last July, a quiet piece of news squeezed past the usual focus on the Karakorum giants. “One of the most remarkable climbs of the season has just taken place on the difficult Rakaposhi (which misses 8,000’er status by just 212m),” it said. Kazuya Hiraide and Kenro Nakajima of Japan had just opened a bold new route on the south side, alpine style.

By the end of that week, a record number of climbers had retreated from K2 because of unstable snow, while a handful succeeded on the Gasherbrums. No one seemed to care much about the isolated, difficult, beautiful — but yeah, not quite 8,000m tall — Rakaposhi. The story of a remarkable climb was passing unnoticed.

Rakaposhi at sunset. Photo: Fawad Malik

In an interview with Rowan White, ExplorersWeb’s bilingual owner, Kenjo Nakajima came off as humble and reflective, considering the confidence needed for a pure alpine-style attempt on an untouched face. Of course, the pair had won the Piolet d’Or the year before for the first ascent of nearby Shispare, so their ability was not exactly a surprise.

Kenro Nakajima and Kazuya Hiraide weren’t even planning to do Rakaposhi. Their original goal was 7,708m Tirich Mir Main. However, delays with the climbing permit made them look for a Plan B. Hiraide knew the Hunza Valley intimately since he had made it one of his life goals to climb all its peaks. They decided to scout the south side of Rakaposhi. Other parties had reconnoitred that line but weren’t able to find a feasible route, so it remained untouched.

Between C1 and C2. Photo: Kenro Nakajima

On June 16, they set up Base Camp in a grassy valley, amid grazing yaks and goats. The pair spent three days acclimatizing and scouting the potential route. They overnighted at 4,500m and 5,900m, then reached 6,100m before returning to BC.

Here, they endured rain and sleet for six days, while distant avalanches echoed through the valley. When the weather finally broke, the forecast gave them a couple of days of cloud, some unsettled weather, followed by a narrow but promising window of sun and calm. That was their play.

They left on June 27 under the predicted cloudy skies, with food and fuel for seven days. After 1,500m of climbing, they shoveled out a platform on a col at 5,200m. The next day, they struggled through fresh snow and past seracs to the foot of an ice wall, sometimes doffing their packs to break trail. They managed to gain a further 1,000m and pitched C2 at 6,200m.

On June 29, they reached the southeast ridge, which they mounted by planting ice screws on the ice wall just beneath it. Soft snow posed a challenge, but they managed to ascend 600m, where they dug out Camp 3. Here, the weather crapped out, as expected, and they hunkered down on June 30 and July 1 during a heavy snowfall.

Above Camp 3 during the summit push. Photo: Kenro Nakajima

Considering the narrow weather window, they decided that they had to make their final push to the summit from C3. At 4am on July 2, they left camp and topped out at noon. The panoramic view including Shispare, the scene of their previous triumph, and K2 in the distance.

At the summit. Photo: Kenro Nakajima

They descended the same way, overnighting at C3 and returning to Base Camp the following day. The route was not overly technical, they reported, but their climb from BC to summit surpassed 4,000m, in highly unstable weather.

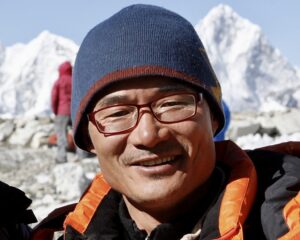

Triumphant summiters back in Base Camp. Photo: Kenro Nakajima

In the interview, Nakajima went out of his way to point out that he is not a full-time professional. He works all year at a real job and self-funds his expeditions during his holidays. When he and Hiraide climb together, Nakajima takes the lead because he is the stronger of the two, while the more experienced Hiraide gives directions and advises his mate while belaying him. Nakajima also doesn’t bother with any special training because, after all, “mountaineering is just walking.”

Far from mainstream goals, fixed ropes and supplementary oxygen, the Japanese climbers quietly achieved one of those dream new lines that many alpinists might point to as the paradigm of true high-altitude climbing, but rarely consider doing themselves. As the seasons go by, we will continue to keep our eyes on the K2s and the Everests… but we will heartily applaud the courage and ingenuity it takes to raise one’s head to the sheer walls of Rakaposhi and break a single trail on its snow-covered slopes.