Bernadette McDonald spent the winter of 2018-19 and the following months on her latest book, Winter 8,000. (It is released today and we’ll review it shortly.) By the time she handed the manuscript to her editor, a fresh winter was on its way. McDonald had planned to escape at the end of it to the blue sea and cool limestone of Greece for some recreational climbing of her own. Then came the lockdown, and everyone’s plans just vanished.

During this enforced layover, ExplorersWeb spoke to McDonald about the book, her career, how the current situation is affecting the mountaineering community and what it takes to synthesize facts, feelings and snippets of memory into coherent stories of lives lived to the fullest in the mountains.

Bernadette McDonald has written 14 books on mountaineering so far, and she is a familiar face at mountain festivals. Yet her original career track tilted to classical piano. How did she eventually focus on climbing?

“It was totally accidental,” she admits. “I was working in the music department at The Banff Centre, but I was also very active in the mountains, so I was volunteering at the film festival. That developed into a job as director of the Banff Mountain Film and Book Festival, which led me to want to write about mountaineering, which is what I do now.”

McDonald divides her time between winters in Banff and summers in the Okanagan, a wine-growing area in south-central British Columbia. Here, she and her husband Alan grow Pinot Noir, Viognier and Syrah grapes in their small vineyard. “It’s a great spot for rock climbing too,” she says. After COVID killed her Greek climbing holiday, she could at least get out to the local crags two or three times a week.

Tying vines in the Okanagan.

This year will also be the first in a long time that she doesn’t visit a mountain festival. “I am a senior citizen, I am not going anywhere,” she said. She is surprised that some festivals are still willing to have audiences. “Banff will be 100 percent virtual, since authorities in Canada prohibit gatherings of more than 50 people, but some of the European festivals are going ahead.” Recently, for example, Trento featured indoor and outdoor events, as well as streaming. And the Piolet d’Or event will be live. “I don’t know how they’re going to do it, because last year, there were about 2,000 people there,” says McDonald.

Still, she acknowledges the temptation to want to gather in person. “Festivals are the only place where the mountaineering community comes together as a tribe, whether you’re a filmmaker, climber, journalist or just someone who is interested in the mountaineering world,” she reflects. “It’s not like hockey or football games: Mountaineering takes place in relatively isolated places, and it’s the festivals where everyone connects, so this year feels kind of lonely.”

Festivals are also a great place to gather ideas for books and to get to know the characters personally. However, climbers are not always keen to share their feelings and experiences -– at least, not to the extent McDonald gets across in her books.

Receiving the King Albert Award for international leadership in mountain culture.

“It totally depends on the characters and how willing they are to share,” she says. “If someone agrees to talk to me over an extended period of time, the chances are that the person actually wants to tell you something. Of course, it will not be 100 percent of the story, but it may be important for that person.”

McDonald doubts whether a first-person climber’s account can reflect an multi-faceted story. Different versions are common, and controversies rarely get cleared up because the people involved were under extreme circumstances, in low visibility or bad weather, with communication problems and personal reasons not to report certain details.

“Each version may be totally true for the person telling it, because that’s the way they experienced it,” McDonald explains. “These partial visions are difficult to manage, but it is also really important to do that…The different sides help a reader understand how complicated the story is.”

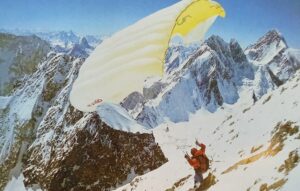

Climbing at Skaha Bluffs, in the Okanagan.

In addition to long interviews with participants, McDonald also speaks to the climbers’ partners, children and friends, who offer a personal perspective. Her stories rarely start at the airport in a foreign country, nor end at a summit or back in Base Camp.

“All these stories have an in-between,” she says. “Maybe they’re training, but they’re also struggling with personal relationships. We are not all world-class alpinists, but it’s good to know that, like us, they have to deal with life and work balance as well, or how to juggle personal goals with the needs of those close to them.”

In cases when the facts of a controversy remain unclear, it must be hard not to support one version over others. “Yeah, it’s the most difficult thing,” says McDonald. “Of course, I have an opinion and sometimes I’d love to take sides, but I don’t really think it is my place. My job is to present the facts as well as I can, and include all the perspectives for the readers, so they can make their own judgment.”

At the Mendi Mountain Film Festival with Krzysztof Wielicki, one of the characters in the book.

Rather than a chronological account of events, Winter 8000 is structured in 14 chapters, one for each 8,000m peak. “In some respects, that is the way history unfolds,” says McDonald. “Each mountain has its own history, but there is also a narrative that takes you through the book, especially if you are interested in characters such as Maciej Berbeka, Krzysztof Wielicki and Simone Moro, who keep evolving as they gain experience.”

The enormity of the task surprised the author. While 8,000m winter climbing may seem like the extreme of extremes, there have been nearly 200 winter 8,000m expeditions so far, and the trend is far from fading. “Organizing all this material was a real dilemma,” she says.

The time is ripe for such a book on extreme winter climbing, because it has become such a quality tag in most quarters. “The challenge now is either very difficult routes on uncrowded lower peaks or winter 8,000’ers, which are a chance to have real adventure and push the standards,” McDonald says.

And it’s not just about K2, which hasn’t been done yet. Last year, Denis Urubko went to Broad Peak and Simone Moro tried the Gasherbrum traverse. But McDonald believes that the focus on K2 won’t stop until it’s been climbed. Although the Polish team preparing for 2021 is currently the most prominent entrant in these sweepstakes, she’s not sure that the expedition will be all Polish or even that it will be the only one in the winter Karakorum with that goal.

McDonald with Denis Urubko.

She says that climbers are relatively comfortable speaking to her, because since she isn’t one of them, she is “not a threat.” In fact, while she is an avid rock climber, alpinist and ski tourer, McDonald has never climbed an 8,000’er. “I don’t know if this is good or bad,” she says. “I just do my best to understand and reproduce what the climbers describe.”