Belgian ultrarunner Peter Van Geit’s first winter experience covered 110 mountain passes and 170,000m of climbing.

When India’s national lockdown ended late last year, Peter Van Geit headed for Dehradun, the capital of the state of Uttarakhand, to begin his first winter expedition in the Himalaya. He spent 85 days exploring Uttarakhand. He crossed 110 passes and hiked 2,050km and 170,000m of elevation gain.

“Every step in one to two feet of snow was draining,” he said. Still, he averaged 25km a day with a 2,000m elevation gain.

Van Geit, a Belgian ultrarunner based in India, has spent several summers running across the Western Himalaya. In 2019, he crossed 150 passes in a 5,000km solo journey. He had planned a new 2,000km journey for March 2020, but that date was unlucky timing for every would-be traveler. When COVID-19 hit, a national lockdown ensued across India.

Instead, for the next four months, using online resources, Van Geit began mapping the Western Indian Himalaya with his friend Aman, who is completing a Ph.D. on Himalayan glaciers. In total, they mapped 2,000 high passes, 700 glacial lakes, 20,000 villages, and 50,000km of hiking routes across Uttarakhand, Himachal, Ladakh, Jammu, and Kashmir.

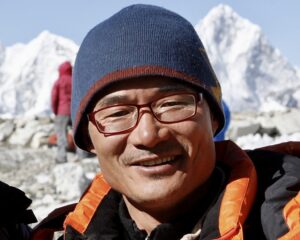

Image: Peter Van Geit

Eventually, the lockdown lifted, and though Van Geit hadn’t hiked in winter before, he set out, using the maps he had spent the previous months creating.

Because the highest passes are only hikeable in summer, he focused on the mid-range passes between 2,500m and 4,000m. “It’s a totally different ball game when snow covers the landscape,” he said.

Photo: Peter Van Geit

Most of the time, all the trails he had painstakingly chronicled were under snow. “You have to use all your instincts to stay on track,” said Van Geit. “Sometimes, you end up exploring off-track, using contour lines and the topography to guide you.”

Van Geit prefers a minimalist style and he made every effort to maintain that, despite the cold. His pack weighed just six kilos. He carried a slightly warmer sleeping bag (rated to -12˚C instead of his -4˚C summer model). It weighed less than a kilo. His four-season solo tent weighed just 400g. He brought no food, having breakfast and dinner in the villages, and not eating during the day.

A local start-up (BlueBoltGear) designed the ultralight equipment. Apart from those few specialty items, his kit was identical to the summer version. He did not wear boots, just light shoes and waterproof socks.

Photo: Peter Van Geit

Unlike his other trips, he did not chart a specific route, but his rough plan was to cross Uttarakhand from west to east. At the Nepal border, he did a U-turn and traversed back. “I could not fix a route in advance because every winter is different, and the snowline goes up and down with every fresh snowfall,” he said. “I selected my passes based on the latest snow conditions…It was very dynamic.”

He learned the hard way that keeping up-to-date with the weather was essential. One night, he slept in an isolated dwelling at 3,700m that is usually only used in summer. At first, the weather was good, but then, “at six am, I heard a loud thundering,” he recalled. “When I opened the door, there was already a foot of snow.”

The snow was piling higher by the minute. “I knew that I would be in a life-threatening situation if I didn’t move,” he said. “It was still dark and there was no visibility…It was trial and error finding my way back below the snowline.” After that, he followed the forecasts more closely.

Image: Peter Van Geit

When he stayed in these remote shelters, he would “barricade the doors” to keep out curious wildlife, such as wild boars and foxes. Sometimes, he could hear steps in the snow outside, and occasionally an animal jumped on the roof.

At this altitude, the temperature dropped to -20˚C, making for some uncomfortable nights in a bag designed only for -12˚C. He also had to sleep wearing his contact lenses because the saline solution had frozen. But the views from these harsh outposts were the best of the trip.

Photo: Peter Van Geit

He only camped in these remote places for 10 of the 85 nights, usually at the higher passes around 4,000m. More often, Van Geit managed to cover the distance from one hamlet to another in a single day.

The plus side of hamlet-hopping was that Van Geit didn’t need to carry food. The odd time that he did not stay in a village overnight, he simply did not eat or drink. “I got used to hiking for 24 hours without water,” he said.

Van Geit was nervous about intruding on remote communities during the pandemic. “I had heard other people who went into the mountains after lockdown faced some pushback, but that was in the more commercial regions,” he said.

In these remote villages, no one wore masks, and Van Geit was the first outsider to pass through in years. “They were very hospitable,” he said. “They saw you as a guest and not a customer.”

He was often offered a place to sleep and home-cooked meals. On a few occasions, he was invited to weddings. Once, he attended a ceremony where the village women were trying to communicate with departed souls. “They were screaming, throwing food as offerings, and there was very intense music and dancing as they tried to connect with the spirits of people who had died that year.”

Photo: Peter Van Geit

He recorded all the routes he used and sent the data back to his home team to upload onto Open Street Maps. As the maps they had created earlier came from a number of sources, sometimes decades old, Van Geit’s traverse of Uttarakhand involved some trial and error. “Ninety percent of the time, the trails worked out pretty well. The other 10 percent no longer existed or I couldn’t find them.”

In the end, his winter travel experiment was a success. Until then, he had only traveled from May until September. “Now I have a 12-month window,” he says. “I can go to high places in the summer and mid-ranges in the winter. I can explore for nine months and map around 6,000km of new trails each year.”