New research concludes that both space travel and endurance swimming can cause your heart to shrink.

A study published last week in the journal Circulation compares how the heart changed during Scott Kelly’s year in space and Benoit Lecomte’s marathon swim across the Pacific Ocean.

The negative impacts of space travel on the human body are well documented. They include sleep problems, reduced muscle mass, bone loss, and changes to the immune system. Until now, very few have associated that reduced muscle mass with the heart. Scott Kelly spent 340 days on the International Space Station between 2015 and 2016 and during that time, his heart shrank by over 25 percent.

Dr. Benjamin Levine, lead author of the study, told The New York Times, “[Kelly] did remarkably well over one year. His heart adapted to reduced gravity…his heart shrank and atrophied kind of as you’d expect from going into space”.

Kelly also happens to be a twin, so NASA carried out multiple biomedical studies to compare what happened to Scott Kelly both physiologically and psychologically in space compared to his brother Mark, back here on Earth. They found a number of differences including body weight, gene regulation, DNA damage, and cognitive performance. Still, they concluded that “Human health can be mostly sustained over this duration of space flight.” For more than one year, they aren’t sure.

Kelly’s heart shrank from the lack of gravity: It did not have to work as hard to pump blood around the body. This loss of mass occurred despite Kelly exercising six days a week while on the space station. “It’s pretty strenuous,” Kelly, now retired from NASA, said in an interview. “You push it pretty hard, more weight than I would lift at home.” He was able to mimic weightlifting through a resistance machine. Though the exercise did not prevent the loss of heart mass, it did work against brittle bones and overall muscle loss.

Space travel vs. endurance swimming

The buoyancy of water gives long-distance swimming a similar impact to the lack of gravity in space. It changes the load placed on the heart due to the horizontal positioning of the body. “You take away the head-to-foot gradient and then put the person in water…It’s just about like being in space”, said Dr. Levine.

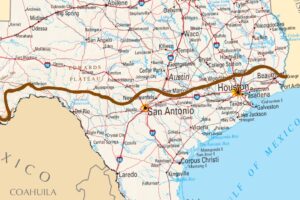

Benoit Lecomte tried to swim the Pacific Ocean in 2018. He covered 2,822km over 159 days before abandoning the traverse. Between swimming and sleeping, his body was in a horizontal position between 9 and 17 hours a day. “When we look at the left ventricle of the heart, we saw about a 20 to 25 percent loss in total mass over the four or five months that Lecomte was swimming,” said co-author Dr. James MacNamara.

Benoît Lecomte tried to swim across the Pacific Ocean. Photo: The Longest Swim

At first, the researchers thought that the physical aspect of swimming for eight hours a day would be enough to counteract the heart muscle shrinking. “I was shocked…I absolutely thought that Ben’s heart would not atrophy,” said Dr. Levine. “That’s one of the nice things about science: You learn the most when you find things you didn’t expect.”

The endurance aspect of the swim meant that Lecomte was pacing himself. “It’s not like Michael Phelps, he’s not swimming as hard as he can,” said Dr. Levine.

Implications for a Mars mission

Though the changes to the heart were not permanent –- both men’s hearts have returned to normal since returning to solid ground — the researchers concluded that low-level activity would not protect the heart in space. This has major implications for longer expeditions into space, such as the mission to Mars.

Dr. Levine spoke to The New York Times about another study (not yet published) that looked at the impacts of six months in space on 13 astronauts. “What’s really interesting is that it kind of depended on what they did before they flew,” he said. Those who did little exercise on Earth but exercised daily in space had their hearts grow in size.

NASA has launched a research project to look at the impacts of space travel on the heart. The next 10 astronauts on long missions will have their hearts closely monitored in space. Dr. Levine will also be working on the project.