When a fire broke out in a 3,000-year-old village near modern-day Cambridge, England, many inhabitants were bound to lose their livelihoods and everything they’d ever known.

But thanks to a nearby river, future archaeologists were sitting on a mother lode.

The Must Farm settlement could have housed 50-60 people at its height in the 9th century BC, the University of Cambridge’s McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research told the BBC. Its eventual contributions to archaeology could prove much more significant than that.

The preservation and deposition at Must Farm allowed us to identify the inventories of the site’s roundhouses. Structure 1 contained 15 pots, a wooden bucket, 3 wooden troughs, 6 socketed axes of different types, 2 gouges, a razor, 2 sickles alongside many other artefacts. pic.twitter.com/hGao7NxOu7

— Cambridge Archaeological Unit (@CambridgeUnit) March 21, 2024

Everyone escaped safely

“The fire may have been disastrous for the inhabitants, but it is a blessing for archaeologists, a unique snapshot of life in the Bronze Age,” said archeologist Mike Parker Pearson of University College London.

Must Farm is not strictly the British Pompeii — at least in terms of human remains. Researchers think all the villagers escaped the Bronze Age disaster. But they’d built their homes on stilts above a riverbed, and when they collapsed into the waterway, a trove of objects inside became preserved for millennia.

Local archaeologist Martin Redding discovered Must Farm by accident in 1999 when he noticed some wooden stumps protruding from a bluff in an old quarry. It looked like other Bronze Age sites. Excavations occurred from 2004 to 2016 and provided a stunningly complete snapshot of Bronze Age life.

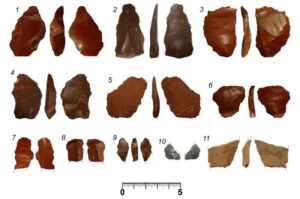

The final tally included four wooden roundhouses and a square entry structure, surrounded by a curved fence. Roofs were straw, with turf and clay for shingling. Although 20th-century mining destroyed about half of the deposit, remnants included over 180 fiber and textile articles, 160 wooden artifacts like containers and furniture, 120 pieces of pottery, 90 metal-worked items, and 80 or more beads, The Smithsonian reported.

Items from distant places

Local manufacturers made most of the items. But some came from Iran (glass beads) and Ireland (a bronze bucket).

The researchers haven’t determined what started the fire. But characteristics like a thin waste layer and relatively unworn timbers suggested it likely burned almost immediately after construction finished. The river silt preserved the surviving materials in distinct detail, including a bowl filled with “porridge-like” mixture.

One of Must Farm’s most exciting discoveries was Pot 44, a coarseware bowl containing a meal of a thick, “porridge-like” mixture of wheatmeal mixed with animal fats. The wooden spatula used to stir the contents was even found still resting against the inside of the bowl. pic.twitter.com/FRxw6zw998

— Cambridge Archaeological Unit (@CambridgeUnit) March 20, 2024

So far, Must Farm has only provided anecdotal insights into the Bronze Age life it briefly supported. Each home had a toolbox kitted out with sickles, axes, and razors. And the porridge showed evidence of a meat-juice topping. Honey-glazed venison completed the menu.

Chris Wakefield, study co-author and an archaeologist at the University of York in England, spoke to the site’s rarity.

“In a typical Bronze Age site, if you’ve got a house, you’ve probably got maybe a dozen post holes in the ground, and they’re just dark shadows of where it once stood. If you’re really lucky, you’ll get a couple of shards of pottery, maybe a pit with a bunch of animal bones,” Wakefield explained. “This was the complete opposite of that process. It was just incredible.”