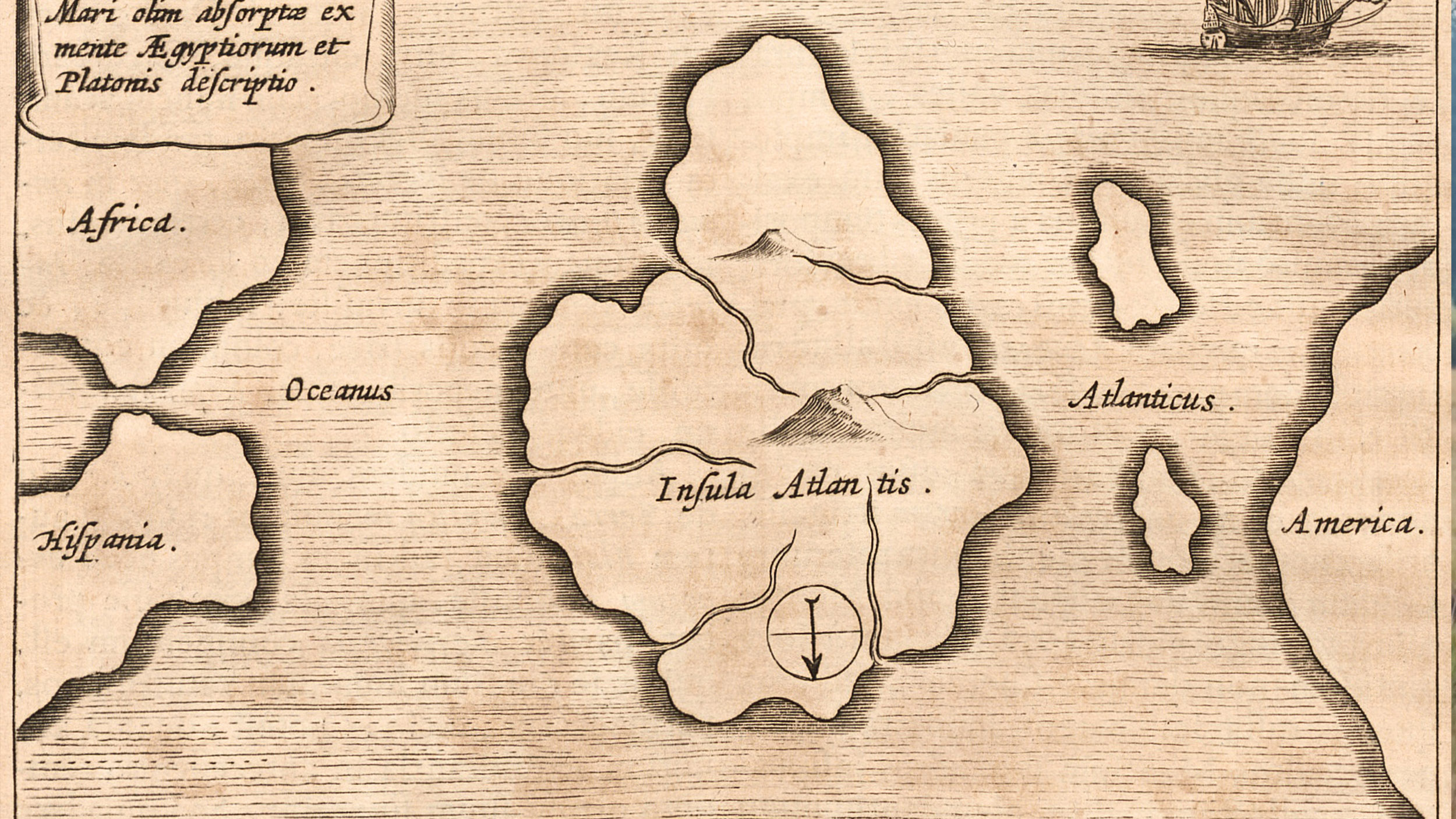

Every exploration buff knows that made-up geography often appeared on ancient maps. The most famous example is that of Atlantis, a myth that originated with Plato and persisted on maps well into the European Renaissance. But as explorers increasingly sought out the world just over the horizon, they brought back tales — often second or third-hand — of other wild lands.

Mapmakers often plopped these tales into existing blank spaces, sometimes as a bit of artistic flourish and sometimes because they legitimately believed the stories.

A website called Map Myths has turned these mythical lands and geographical features into a surprisingly thorough interactive experience. And it’s a must-visit. Users can click on the names of these mythical spots for capsule explanations of how they originated, how they were dispelled, and sometimes who went looking for them. Users can also view the historical maps where the myth in question appears.

Here are a few of the most interesting examples.

The main page and interface of Map Myths. Photo: Screenshot

Wishful thinking

Sometimes, a geographical feature ends up in a mapmaker’s visual lexicon through the sheer power of wishful thinking.

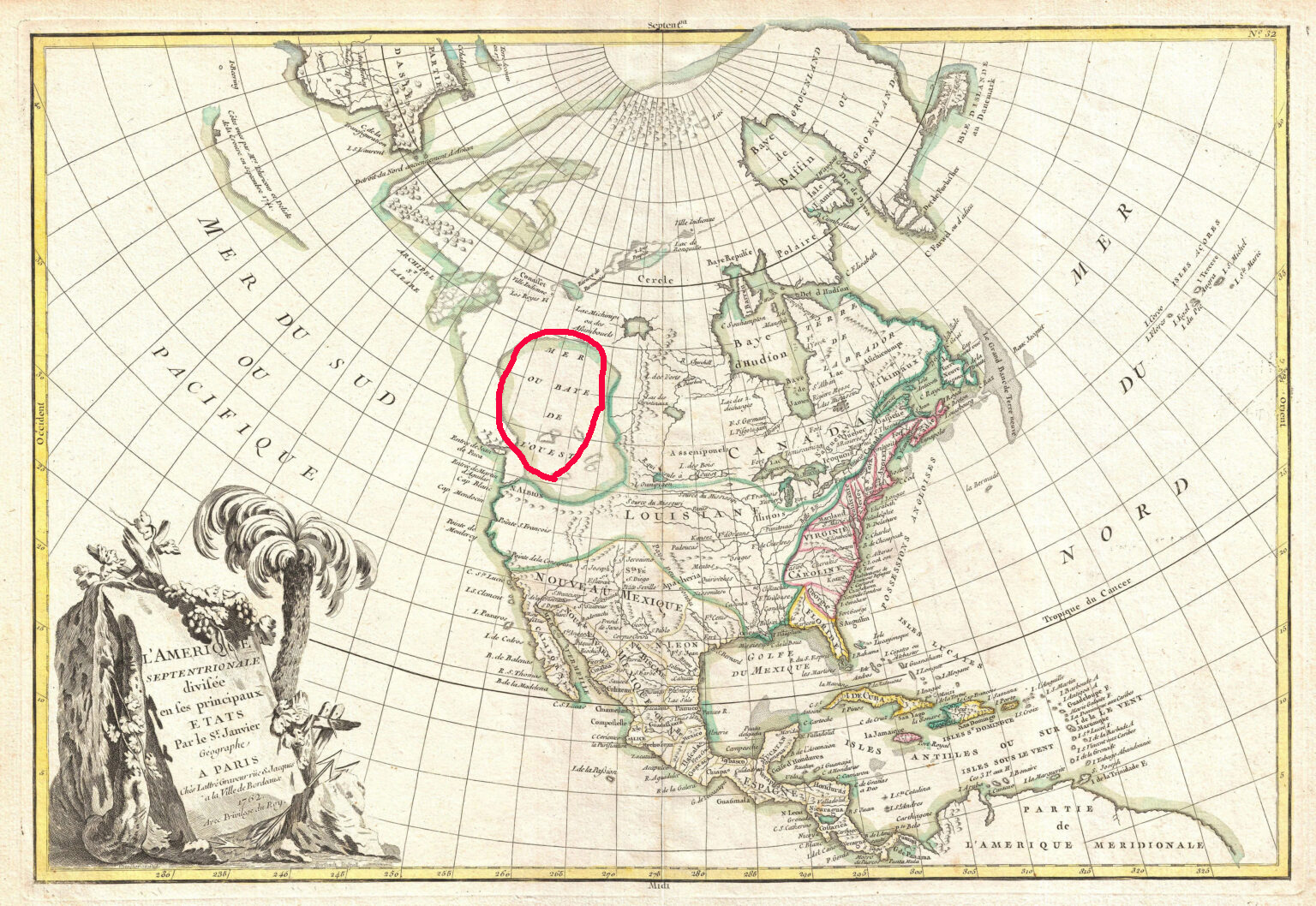

When 16th-century explorer Giovanni da Verrazano peered over modern-day North Carolina’s Outer Banks islands, he laid eyes on Pamlico Sound. The sound is the largest lagoon on the United States’ eastern coast, so when Verrazano couldn’t see the other side of it, he optimistically assumed it was the Pacific Ocean.

This notion was dispelled quickly as more and more colonists and explorers charted the New World, but the idea of a great “Sea of the West” hung on long after Verranzano’s day.

A map from 1762 showing the ‘Sea of the West.’ Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Partly, that’s because a navigable, coast-to-coast water route through North America would pay huge economic dividends to whichever power discovered it. The idea was just too lucrative to let go. According to Map Myths, cartographers included the “Sea of the West” on more than 200 maps during the 18th century.

James Cook’s exploration of the Pacific Northwestern coastline diminished the chances of the Sea being real. Lewis and Clark weren’t expecting to find it during the Corps of Discovery’s journey westward. But Thomas Jefferson — then President of the United States and the expedition’s progenitor — would have been more than happy if they did.

Western Europe hopes against hope

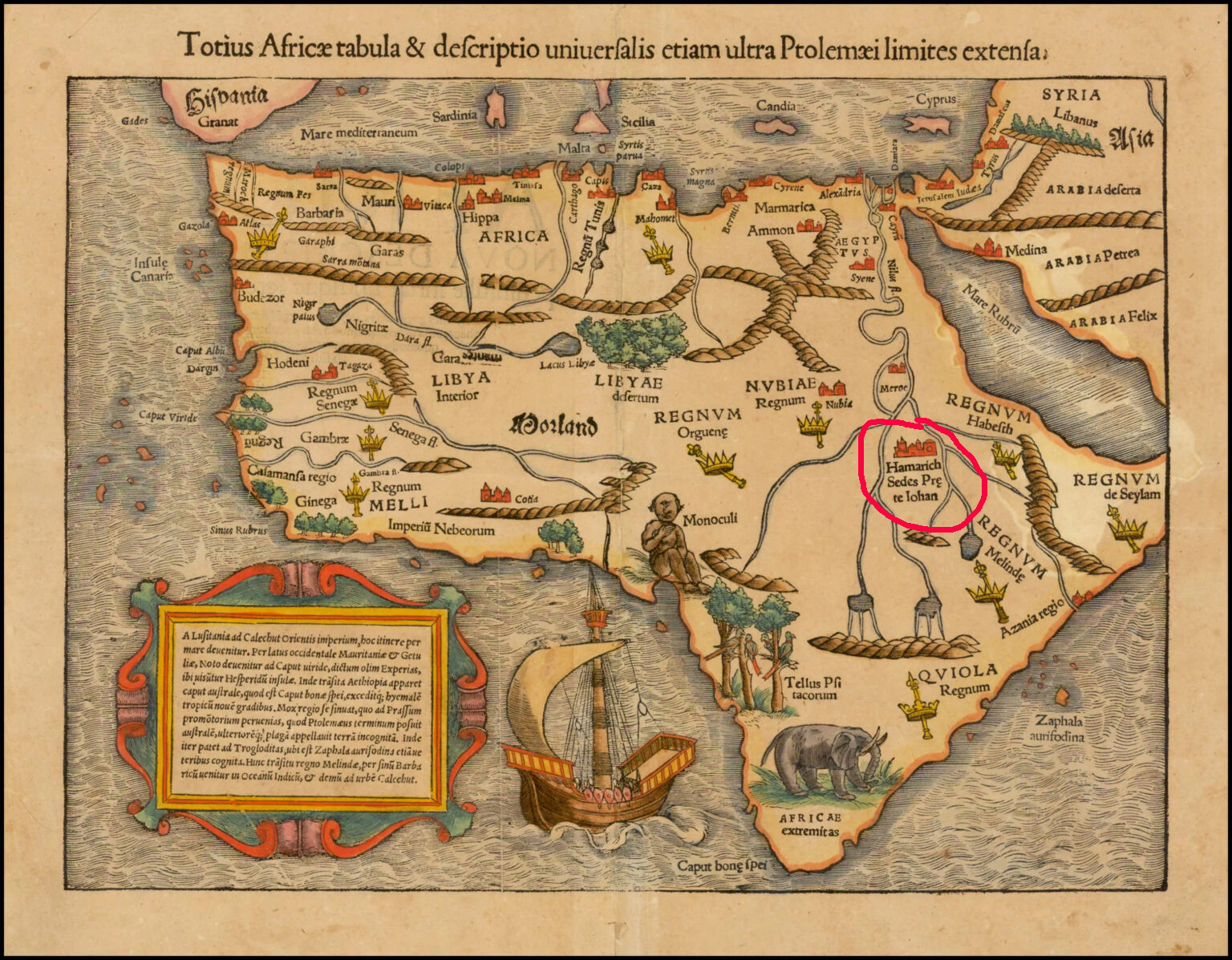

The legend of Prestor John, a powerful and saintly Christian king living somewhere in the Far East, first arose in the mid-1100s AD. By the time European crusaders found themselves outmatched by Islamic military tactics in the Crusades, Prestor John was more than a fairy tale in the minds of many. He or his descendants were a much-hoped-for fighting force that could pressure Islamic armies from a second front.

As it turned out, such a fighting force did arrive to smash into the Islamic world, but it turned out to be the Mongols. Under Genghis Khan, the Mongols swept into Persia in the early 1200s, eventually sacking Baghdad. The unstoppable Mongols effectively ended the powerful Abbasid Caliphate, a turning point in human history if ever there was one.

This 1550 map shows ‘The Kingdom of Prestor John’ at the confluence of the Nile sources. Photo: Stanford University Libraries

It eventually became apparent that Prestor John’s legendary kingdom must lie elsewhere, so mapmakers began placing it around modern-day Ethiopia. Christianity in Ethiopia dates back to the fourth century AD, and the region was far enough removed from Western Europe to maintain a sense of mystery. It took another 200 years or so for Prestor John’s imaginary kingdom to disappear from African maps.

But before it did, it inspired Europeans to explore Asia and Africa with religious zeal.

Demons and castaways

Almost every map created during the Age of Exploration was speckled with phantom islands.

It’s hard to pinpoint the origins of many of these mythical islands — usually a blend of legends and sailors’ tales filtered through time and many mouths. But in at least one case, we can look back at a true story to see the genesis of a phantom island.

In 1542, Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval, a French nobleman and privateer, set out for New France (modern-day Quebec) to take up his post as the Lieutenant General of the colony. Accompanying him was Marguerite de La Rocque de Roberval, a young woman and relative of the freshly appointed colonial official. Marguerite took a lover on the voyage, and this behavior so scandalized the privateer that he marooned Marguerite, her servant, and her lover on an “island.”

The Isle of Demons is visible on this map from the early 1600s in the upper right-hand corner. Photo: Public Domain

Eventually rescued

Marguerite later gave birth under these circumstances, but her baby, her lover, and the servant all died during the years they were marooned. Marguerite was eventually rescued by Basque fishermen.

Once she reached Europe again, Marguerite’s tale became widely known. Mapmakers had already been including an “Isle of Demons” on maps of the Newfoundland coastline, noting it as a spot where all manner of hardships might befall unwary sailors. With the young women’s tales of privations firmly lodged in the public imagination, the phantom island quickly became the setting for the marooning. In reality, it was most likely a region around Harrington Harbour, Quebec — not an island at all.

Still, the Isle of Demons continued appearing on maps well into the mid-1700s.

You can easily — and happily — spend a whole afternoon exploring the mythical kingdoms, islands, and mountains inked onto the maps of yesteryear. Check out Map Myths here.