A lot of contemporary adventure is long on athletics and short on imagination. Is it really exceptional any more to jumar the South Col route on Everest? Or to be the 1,401st person to climb Mount Vinson in Antarctica?

Some might argue that the great adventures have already been done, but even that is not true. The last successful North Pole expedition was 10 years ago; only one party has gone to the North Pole and back to land; no one has done a solo round trip. No one has skied entirely across Antarctica. The first kayak expedition entirely through the Northwest Passage only took place last year; no one has kayaked the ice-choked and even more difficult northern route through that Passage. Hiraide and Nakajima perished this past fall, attempting the unclimbed West Face of K2. No one has reached the North Magnetic Pole since the 1980s, before it began its tear across the Arctic Ocean toward Russia. There is still a lot out there, even for iconic goals.

On the mud flats of James Bay in northern Quebec. Photo: Justin Barbour

Admittedly, it’s easiest to find original routes that aren’t as well-known as the North Pole or K2. Canada’s Justin Barbour did that this year. The former Newfoundland school teacher turned content creator spent an entire year traveling 3,800km from Puvirnituq, in northern Quebec on the shores of Hudson Bay, to Cape Pine, the southern tip of the island of Newfoundland.

Puvirnituq? Cape Pine? Not exactly iconic. Likely, no one will ever re-do this journey. It’s a one-off. But give Barbour marks for that. It shows imagination to figure out your own path. It also suggests someone educating himself about the land, not just copycatting the one or two routes he’s heard about.

A full year

“I want to experience a full year in the northern wilderness,” Barbour told ExplorersWeb before the journey. “To experience the four seasons as the indigenous people of the area have.”

Barbour first came to ExplorersWeb’s attention in 2018 when he tried to trek and canoe 1,700km through the same general region from Labrador to Hudson Bay. He started late and had to abort after about 1,000km as winter set in.

“I had enough summer experience, but my winter skills in the subarctic cold weren’t there yet,” he admitted.

Six years later, the 36-year-old Barbour is more experienced. He started in early July of 2023 at Puvirnituq, an Inuit village with a population of about 2,000 on the shores of Hudson Bay. Thirty-eight days and 692km of downriver paddling and upriver canoe hauling with his dog Saku, he arrived at his first checkpoint, the village of Tasiujaq on James Bay.

Barbour and Saku. Photo: Justin Barbour

Waiting for winter

It was mid-August, and a chill was already in the air, as the short arctic summer quickly turned to fall. Barbour continued south in his canoe, trying to make 700km to his next stop, the former mining town of Schefferville, before winter set in.

He didn’t quite reach it. A helicopter pilot friend conveyed him to Schefferville. He lived for a few weeks in his heated bush tent outside of town, as he waited several weeks — like the trappers and Innu people of the interior used to do — for the brooks and lakes to freeze solidly and for the new snow to harden under the region’s bitter northwest wind.

Finally, on Jan. 4, 2024, his pilot friend conveyed him back north to his pickup point. Saku, a fair-weather dog, had gone home. Barbour continued south alone on snowshoes, hauling a traditional-style toboggan with a single leather strap across his chest. That was how Labrador’s old Height of Land trappers did it. These toboggans are longer and narrower than kids’ versions and have high, upturned noses for riding over snowdrifts.

Photo: Justin Barbour

Skis and a fiberglass pulk, like those Antarctic skiers use, would be quicker, but Barbour preferred a traditional style. And his canvas tent, hung from a frame of black spruce trees and heated by a small wood stove, is far more comfortable than a nylon tent in the frigid northern Quebec interior, where temperatures can drop well below -50˚C.

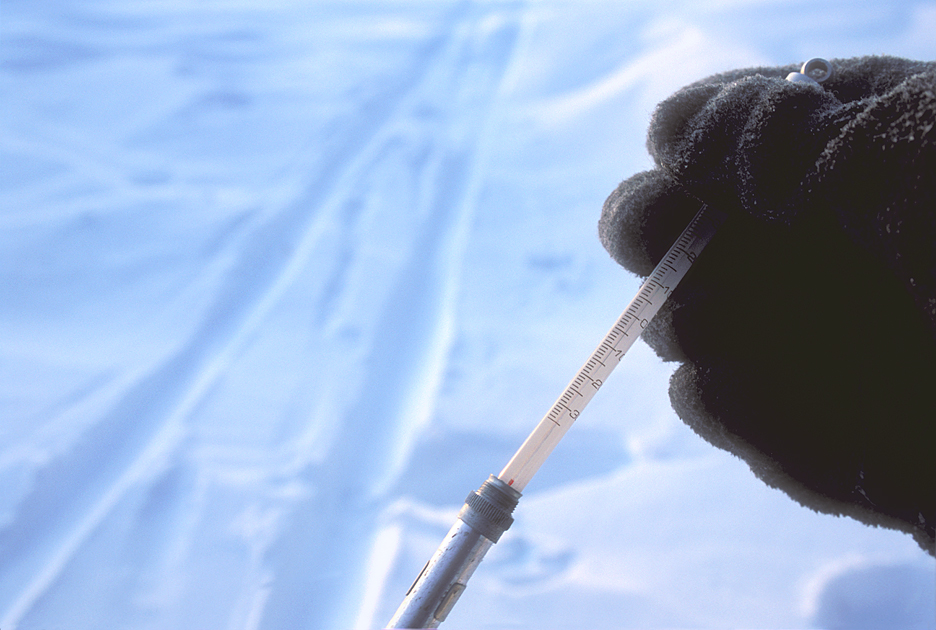

A frosty day in northern Quebec. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Spring arrives

He stuck as much as possible to open lakes, where the snow was harder than in the open forests of black spruce and tamarack. After several hundred kilometers, he crossed the Trans-Labrador Highway, a wilderness road that connects Labrador with the rest of Canada, and then continued south overland toward the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

A small wood stove can heat a canvas tent to room temperature, even if it’s -40˚ outside. Photo: Justin Barbour

But spring was coming on, snow cover was thinning out, forests were thicker, and the south-flowing rivers he had to follow were opening up. The toboggan-hauling season had ended. Rather than wait a month for the rivers to open completely so he could canoe again, he had his helicopter friend convey him 267km back to the Trans-Labrador Highway. Here, he cycled 1,500km to the south coast of Labrador.

By this time, “I was starting to wear thin,” he admitted. So he decided against kayaking the 18km Strait to the island of Newfoundland. Instead, he took a ferry across.

Then he hiked another several hundred kilometers to Cape Pine, the southern tip of Newfoundland. In the end, he spent his full year (372 days, to be precise) in the wilderness, traveling by a variety of conveyances — 1,150km of canoeing, 700km of snowshoeing, 1,500km of cycling, and 550km of hiking.

Barbour admits he’s not sure what he’ll do next. Such long journeys disrupt every other aspect of one’s life, and most ultra-marathon adventurers do only one of these before starting to put down roots. A follow-up project that lasts only one or two months may feel small by comparison, and most tend not to do them. But we’ll keep watching Barbour’s social media, just in case.