From the summer of 2015 to the spring of 2016, beachgoers from Alaska to California encountered something very strange: the bodies of dead and dying seabirds.

The common murre, scientific name Uria aalge, is a type of auk. Long considered one of the most successful seabirds in the Northern Hemisphere, it’s 38 to 45cm tall with a 60cm wingspan. They spend much of their time at sea but breed in large, loud colonies on cliffs and along coasts.

Washing up dead and emaciated in large numbers was uncommon for this highly adaptive bird. When researchers examined the bodies, they found that the murres had starved to death. Then, 62,000 of them drifted to shore. Those that remained alive weren’t breeding, imperiling the population even more.

But the cause and the scope of the catastrophe were difficult to measure. It is only now, almost a decade after it began, that researchers understand what happened.

This dramatic comparison shows the devastation to one murre colony. Photo: United States Fish and Wildlife Service

‘The Blob’

Beginning in late 2013, an unprecedented marine heat wave, dubbed “The Blob,” began. A high-pressure ridge in the Pacific created a massive pocket of warm water. Between 4˚ and 10˚ higher than average local temperatures, The Blob extended as much as 1,600km across at depths up to 100m.

It surged across the ocean between Asia and North America, landing in the Gulf of Alaska in 2015. There, it remained for about a year before splitting into thirds. Now, three smaller Blobs haunt the Bering Sea, the waters off California, and the coast of the Pacific Northwest.

While the original Blob was in the Gulf of Alaska, it caused an increase in mortality across the top levels of the marine ecosystem. Fin whales, auklets, fur seals, sea lions, cod, flounder, and many more species died or failed to reproduce from 2014 to 2017. But the devastation of the murre was on an unprecedented scale.

To measure the scale of the mortality, researchers had undertake the grim work of counting the bodies. Photo: USFWS

The ectothermic vise

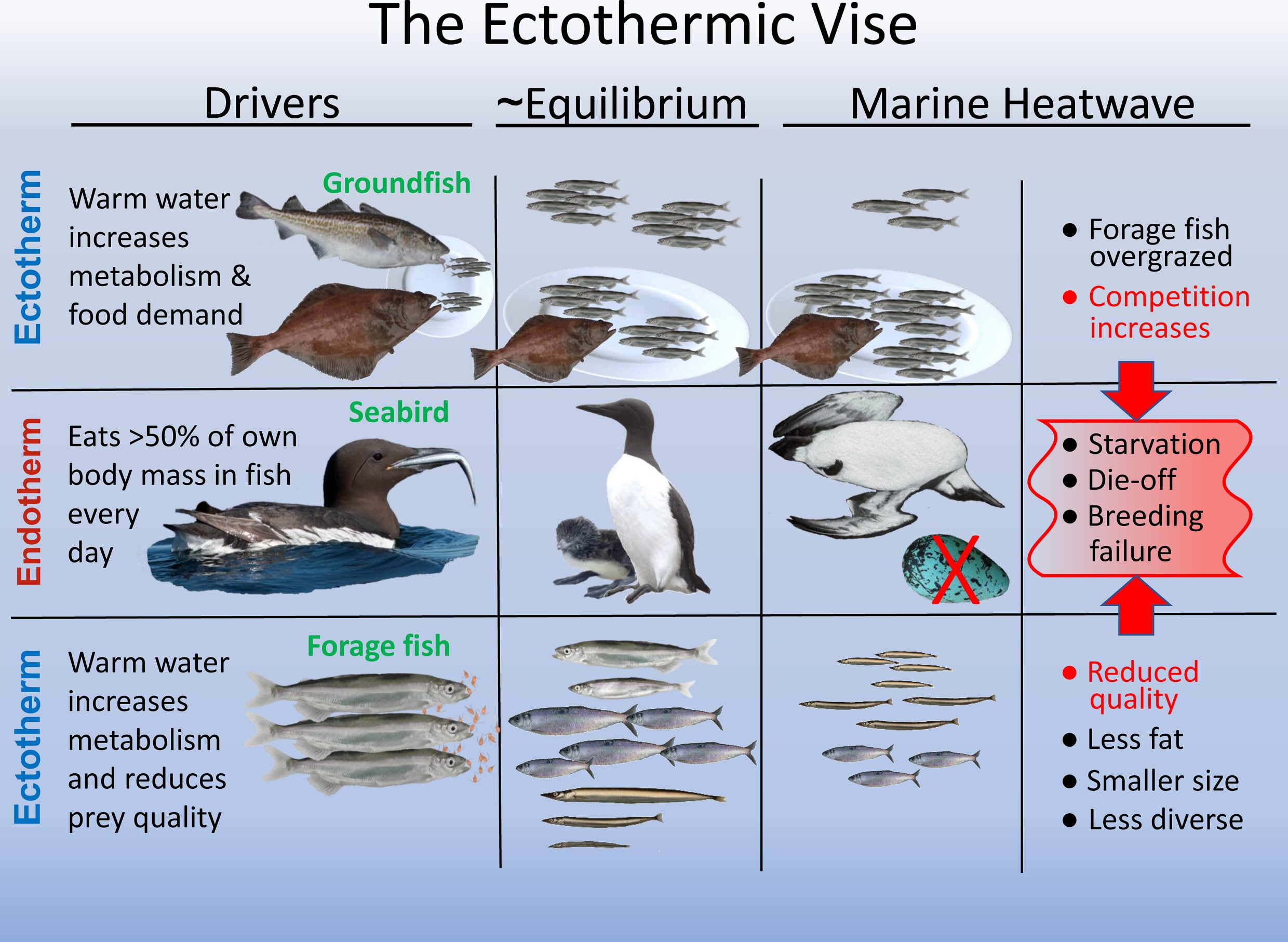

Every level of the ecosystem was affected, leading to a cascade of mortality. The heat killed off plankton, the essential base of the marine food chain. At the same time, the cold-blooded fish, which are more active in warmer water, needed more food to sustain their increased activity.

This created conditions that researchers have dubbed an “ectothermic vise.” The ectothermic (warm-blooded) seabirds were trapped between the changing populations of cold-blooded forage fish (which eat plankton) and ground fish (which eat forage fish). The increasingly active ground fish competed with the murres to eat the starving forage fish. This led to an even more extreme lack of food for the seabirds.

Only a small percentage of the birds that died ended up washing ashore, so it was difficult for scientists to get a handle on the total numbers. But they estimate that as many as four million murres died during the 2015-2016 mortality.

“The magnitude of this die-off is without precedent,” said biologist John Piatt. In some populations, half the murres died of starvation. It was the “largest mortality event of any wildlife species reported during the modern era.”

The diagram above shows how the heat wave put pressure on the murres from both above and below. Photo: Piatt JF, Parrish JK, Renner HM, et al.

The future of the murre

The large and raucous colonies of murres remain quieter, not just because of the starvation event but also because of a lack of new chicks. During 2015-2016, 22 colonies failed to produce a single chick, and many others had fewer than usual.

It’s been almost a decade since The Blob descended upon the common murre. Time, however, has not healed all wounds. The population is not recovering. Why this is, researchers aren’t entirely sure. One theory is that the much smaller colonies are harder to defend. Fewer birds mean more eggs stolen by gulls and other predators. This, in turn, means fewer birds.

They may bounce back in time, although the world hasn’t seen the last of The Blob. As climate change warms the oceans, delicate marine ecosystems will face population collapse, and the common murre may become common no more.