In the end, in the dark, it all came down to three things — experience, good judgment in the face of uncertainty, and penguin meat.

It was 1903, their second winter on the White Continent. Swedish geologist Otto Nordenskjold and five men under his command shivered in a hut on Snow Hill island, off the eastern coast of the Antarctica Peninsula. The intention had been to overwinter once on the spit of land, conducting scientific observations while they waited for their ship, the Antarctic, to pick them up. It was slated to be a nine-month layover.

The first winter had been brutal but manageable. Nordenskjold and his men were prepared and had even managed a 645km, month-long mapping expedition along the coastline. They returned just in time for their appointed pickup. While the expedition had been a scientific success, it wasn’t without setbacks. Several dogs had died in a blizzard, and fierce winds had toppled an outbuilding and blown away a boat. Doubtless, the men were looking forward to putting the continent behind them.

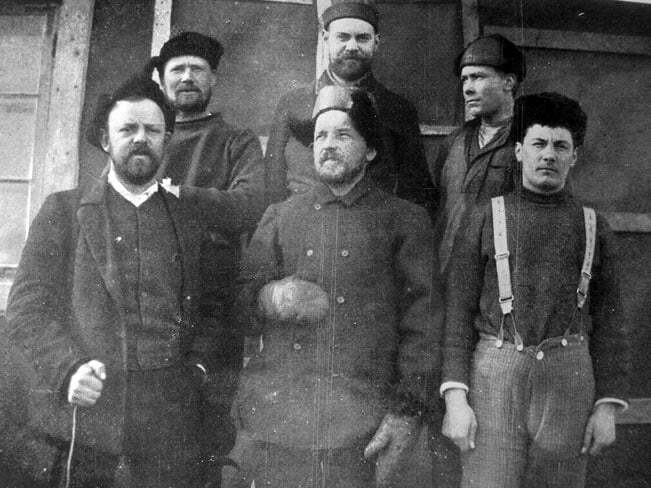

Otto Nordenskjold (bottom center) and the Snow Hill Island party. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

An empty horizon

But when the appointed moment came, the Antarctic failed to appear. Days turned into weeks, and the ice closed in. Soon, it was apparent. Nordenskjold and his men were in for another dark winter.

Fans of polar exploration might already be familiar with Otto Nordenskjold and the 1901–1904 Swedish Antarctic Expedition. While perhaps not as famous as the top-tier polar racers, Nordenskjold was a major player in his day. If his name has faded slightly over the last century, it might be because he was always more interested in geology than he was in planting a flag.

But the full tale of the Swedish Antarctic Expedition — and the cataclysmically bad luck it endured — is always worth telling. And if you’re new to the story, well, you’re in luck.

The expedition was Nordenskjold’s brainchild. A geologist and geographer, the Swiss explorer wanted to fill in blank spaces on the Antarctic map, particularly the eastern side of the Antarctic Peninsula. Privately funded, the expedition would leave Nordenskjold in crushing debt for the rest of his life. But first, the men had to make it home.

Norwegian Carl Anton Larsen captained the Antarctic and was in overall command of the expedition. Larsen was an experienced polar explorer — in fact, he was the first person to ski in Antarctica. He was also the first person to discover fossils on the continent.

Carl Anton Larsen. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Iced over

While Nordenskjold’s men scouted the Antarctic coastline, Larsen and the rest of the expedition explored the island of South Georgia. After nine months, the Antarctic attempted to sail back to Snow Hill Island to pick up Nordenskjold’s men.

But their route was completely iced over. Larsen was too seasoned to be so easily stymied and quickly came up with a backup plan. He deposited three men, led by archaeologist Gunnar Andersson, at Hope Bay on the northernmost tip of the peninsula. The party was to travel southward overland, rescue Nordenskjold and his men, and return for pickup: A 270km round trip.

Andersson’s party began its journey south, but when the men reached the portion of the journey that entailed crossing sea ice, they stopped in horror. The ice they’d intended to traverse was gone. They turned around and returned to Hope Bay, but found little hope when they arrived. The Antarctic had already sailed.

Abandon ship

The dauntless Larsen hadn’t given up on a Snow Hill rescue, and he steered the Antarctic back into the Weddell Sea. But the treacherous ice closed swiftly, and 45km from land, the ship was fully frozen in. The cataclysmic forces quickly did their work, and Larsen and his remaining men abandoned the ship after six weeks.

The ‘Antarctic,’ frozen in ice. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

It took two weeks of nerve-wracking ice-floe hopping to reach the safety of Terra Firma. They almost didn’t make it — a major storm rolled in a day after they reached Paulet Island in late February 1903. Had they still been on the ice, all 14 of the men might well have perished.

The expedition was now split into three groups: Nordenskjold’s party on Snow Hill Island, Andersson’s party at Hope Bay, and Larsen’s party on Paulet Island.

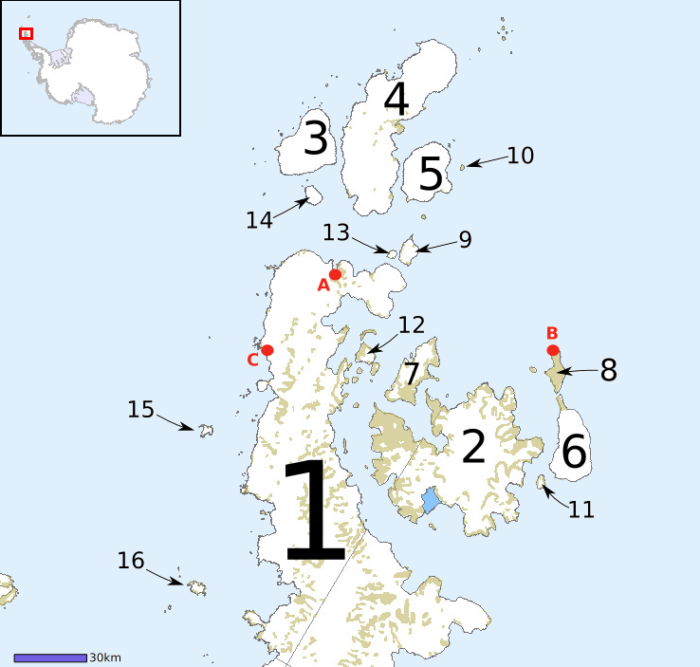

A map of the Antarctic Peninsula. “6” is Snow Hill Island. “A” is Hope Bay. “10” is Paulet Island. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

None of them had any means of communication. None of them knew the fate of the other parties. All of them were facing an Antarctic stay of unknown duration with dwindling supplies. And as far as the outside world was concerned, the Swedish Antarctic Expedition had simply vanished.

A grim winter

It was a long and difficult winter.

At Hope Bay, Andersson’s party built a drafty shelter from stones, covered it with a salvaged tarpaulin, and insulated the floor with penguin skins.

At Paulet Island, Larsen’s party built a similar rocky hut but at least had sailcloth to work with. They also were able to use a local population of seals for insulative animal skins.

The remnants of the Paulet Island hut. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

On Snow Hill Island, Nordenskjold’s party, though the first to become stranded, had the most supplies and the advantage of a purpose-built shelter.

All three parties mostly lived on penguin meat as the long dark dragged on. Oil rendered down from penguin fat provided their fuel for heat and cooking — a smoky, rancid way to prepare a meal and warm the hands if ever there was one.

As spring arrived, Larsen set his sights on Hope Bay. He divided his party yet again, taking five men and rowing for the bay with the expectation of finding both Andersson’s and Nordenskjold’s parties awaiting him. It was a dicey five-day row, but they made it.

When Larsen arrived, all he found was an abandoned stone hut. Andersson’s party had vanished.

Unlikely reunions

Again, Larsen’s level head and experience prevailed. Intuiting that Andersson and his men must have overwintered at Hope Bay and then struck out overland for Snow Hill Island, Larsen and his five men hopped back in their boats and began rowing again.

Larsen had calculated correctly. When spring arrived, Andersson’s men had indeed traveled south once again, this time finding enough pack ice to make the crossing to Snow Hill Island.

On Oct. 12, 1903, Nordenskjold looked up to see three shabby, heavily bearded, soot-blackened men shamble out of the white. It was Andersson’s party.

At least some of the expedition was back together, but of course, none of the men now huddled on Snow Hill Island knew the Antarctic’s fate.

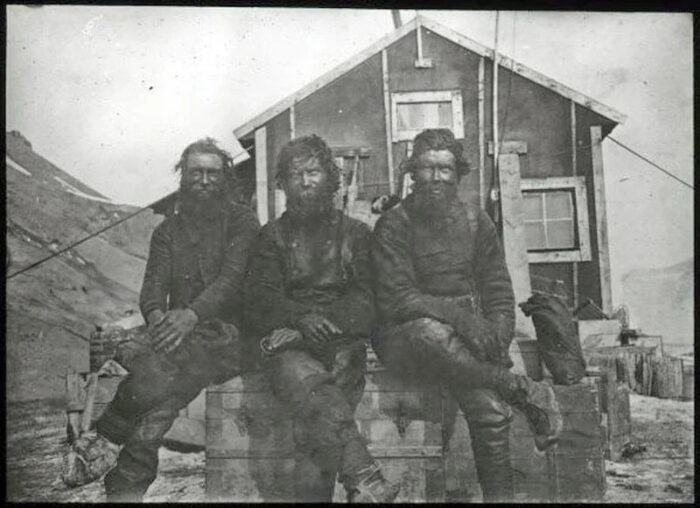

Andersson’s party at the Snow Hill Island hut. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

They were also unaware that help was on the way. Larsen, always prepared for the worst, had made one last contingency plan — a plan that had now been activated. When the expedition made port in South America on the way to Antarctica, Larsen asked the Argentinian navy to come and search if the expedition had vanished. This they did, dispatching the Uruguay that spring. For once in nearly two years, something went right. The ice was cooperative. Two weeks after Andersson’s party arrived at the hut, the Uruguay appeared at Snow Hill Island.

Overjoyed

The rescued men were overjoyed. With hands shook, pipes lit, and fresh food parceled out, rescuers and rescuees alike then turned to the final piece of the puzzle. Where were Larsen and the Antarctic?

At that moment, and in a bit of timing so unlikely that it would be unbelievable if this story was a piece of fiction, Larsen appeared in the hut. He and his men had successfully rowed and sailed to Snow Hill Island. They’d seen the Uruguay as it approached the site.

With all the Snow Hill men now aboard, the Uruguay set sail for Paulet Island to rescue Larsen’s remaining men.

In the end, all but one man from the Swedish Antarctic Expedition survived. One of Larsen’s party had died of heart failure during the second winter, an event that might have occurred even without the hardships the expedition endured.

By polar disaster standards, it was an astounding feat. It speaks not only to the physical endurance of the men, but of just how well-stocked the expedition was. Even split unexpectedly into four groups, the expedition had enough leadership, experience, and proper judgment to make good calls consistently.

Aftermath

Despite the many setbacks, the Swedish Antarctic Expedition was widely hailed as a success. The men had charted much previously unexplored territory and returned home with a vast cache of geological and biological samples.

Larsen settled into the (relatively) more comfortable life of an Antarctic whaler, eventually moving his family down to a South Georgian site he’d scouted while overwintering there in 1902. He died in 1925 at the age of 64.

Nordenskjold became famous in his home country and abroad, but the personal debt he incurred as a result of his expedition haunted him for the rest of his life. He became a professor at the University of Gothenburg and mounted expeditions to Greenland, Chile, and Peru over the next two decades. He was killed in a traffic accident in 1924, at the age of 58.