Australia has a reputation for venomous wildlife, particularly spiders. A good part of that reputation comes from the deadly Sydney funnel-web spider, Atrax robustus.

This particular spider has evaded easy categorization. Different specimens across its range vary widely in size and, crucially, the amount and deadliness of venom. But researchers have taken a closer look at this spider and discovered something unexpected: it isn’t a single species at all.

This male specimen, shown from above and below, was one of the spiders used by researchers to define the new species. Photo: F. Loria et al.

Venomous menace

First described by English clergyman and noted arachnologist Octavius Pickard-Cambridge in 1877, the Sydney funnel-web spider is responsible for over a dozen recorded deaths. It is considered the most venomous spider in the world. The venom is more potent in males, which are also more aggressive and tend to wander in the open after a rainfall. They also tend to hang on or bite multiple times once confronted.

The initial bite is painful, and symptoms set in quickly, within an hour of the bite. The Sydney funnel-web deploys a neurotoxic called Delta atracotoxin. This D-atracotoxin causes breathing difficulty, wild fluctuations in blood pressure, muscle twitches, vomiting, and nausea. Other symptoms include uncontrollable weeping, sweating and salivation.

Luckily, there is an antivenom. Since it was developed in 1981, there have been no recorded deaths from the Sydney funnel-web. Producing this antidote requires a large number of captive spiders, which researchers at the Australian Reptile Park carefully “milk” for their venom.

This program received a donation of one such spider in early 2024. When measured, this individual measured 7.9 centimeters or 3.1 inches from leg tip to leg tip. Named “Hercules,” he was the largest Sydney funnel-web spider ever recorded.

Actually, it turns out he isn’t. He’s an entirely new species.

Hercules, shown here beside an Australian 50-cent coin, measures nearly eight centimeters. Photo: Australian Reptile Park

A puzzling species

Massive specimens like Hercules and Colossus, the previous largest specimen, collected in 2018, raised questions for researchers. Why did the Sydney funnel-web vary so widely in size and lethality? Nearly 150 years after the species was first defined, it was time to look into this.

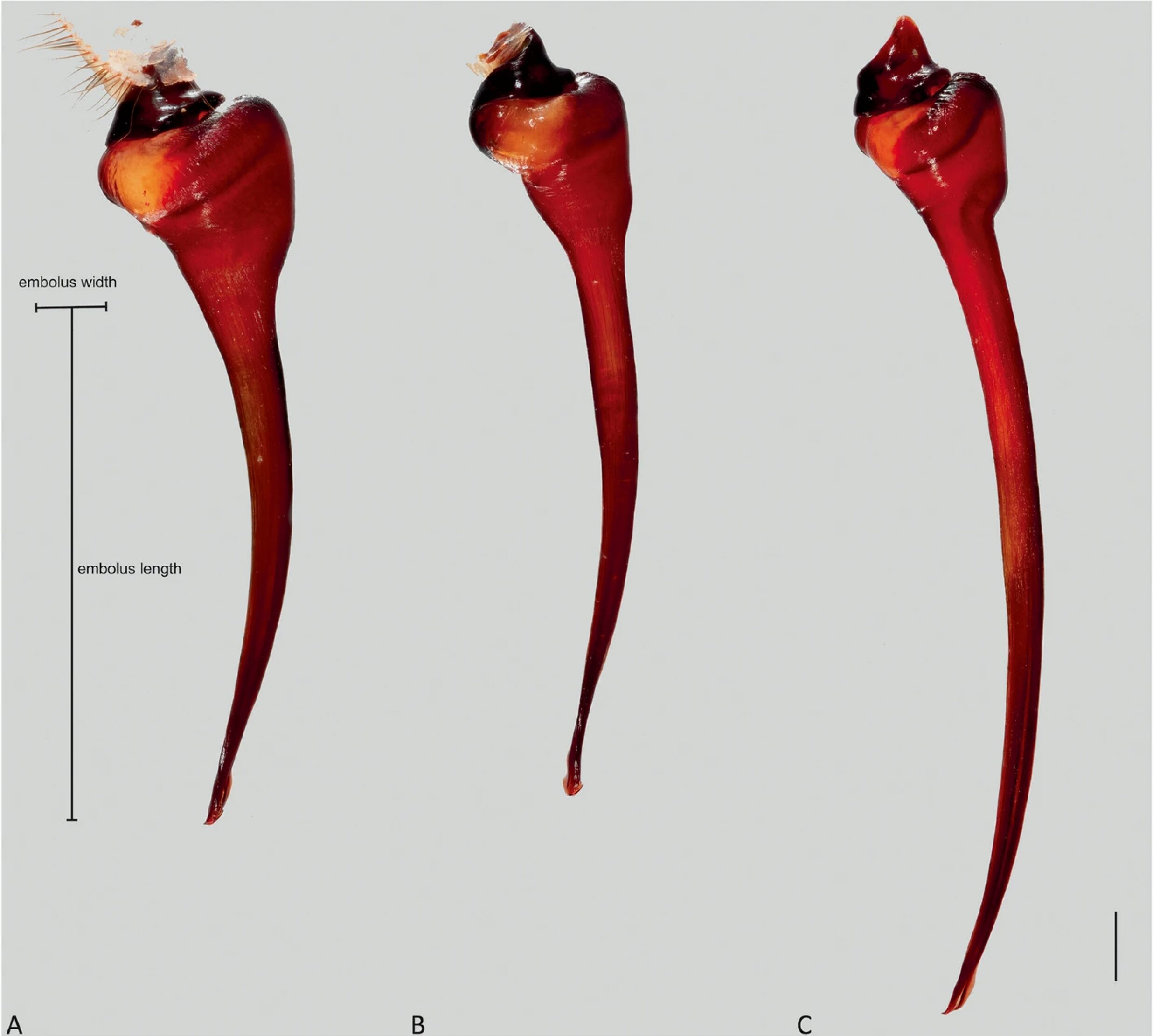

Researchers from the Australian Museum, Flinders University, and the Leibniz Institute in Germany collected several specimens, including the original holotype used to define the species in 1877. Then they carefully measured every part of the spiders, from fang length to internal genitalia.

They also performed genetic analysis on 57 of the specimens, testing for the degree of difference between different groups. They found three distinct clades, which matched the geographical distributions and physical differences they observed.

So the one species was actually three. They estimate that the spiders diverged from each other in the late Miocene, between 13 and 2 million years ago.

A comparison of embolus length and appearance between the three groups. Photo: F. Loria et al.

The ‘Big Boys’

The “true” Sydney funnel-web, and the most common of the three, will remain Atrax robustus. A second mountain-dwelling variety is now officially Atrax montanus. The final, larger, more venomous species is officially the Atraz christenseni. Researchers are calling them “Big Boys.”

Big Boys have a small range: only the area surrounding and to the north of Newcastle. The Big Boys also tend to build more cryptic funnel webs, making their burrows harder to spot than those of their smaller and more common cousins. This and their limited distribution may be why they were not previously identified as a unique species.

This discovery isn’t just great news for fans of large, extremely venomous spiders. It may be important for developing antivenom. The new species differentiation will help make better antivenom and allow doctors to predict how serious a given bite will be.

Their exact haunts have not been made public, as their unusual size and limited distribution, so close to an urban area, may make them vulnerable to overexcited collectors. While the Big Boys may seem fearsome, researchers are already worried for them.

“Conservation measures may be warranted,” the study warns, in order to preserve the iconic Sydney funnel-web family.