In 1863, a Russian paleontologist and mining engineer made his way through the Eocene strata of the Caucasus to the shores of the Caspian Sea. His name was Hermann Vil’gel’movich Abikh, and he had heard tell of ghost islands and strange fireballs over the water. As an expert on petroleum and natural gas, this had caught his attention.

Sitting in the rich blue waters off the coast of Azerbaijan was an island the size of a basketball court. By Abikh’s measure, it stood 3.6m above the water– higher than the elevation of Amsterdam. And yet on maps of the shoreline from the previous year, the island — called Kumani — sat a full 2.4m lower in the water.

What had happened? And did it have anything to do with the ever-burning flames seen on nearby Dashly Island?

Two centuries later, NASA geologists reviewing satellite footage of the Caspian Sea found themselves asking the same questions.

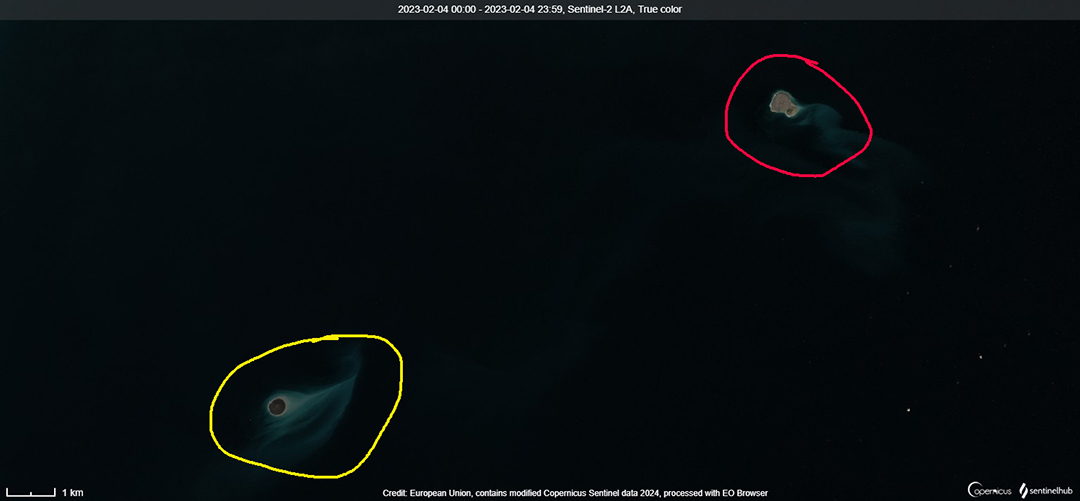

Dashly Island, upper right (circled in red), was the location of a massive explosion in 2021. The island to the lower left, Kumani (circled in yellow), did not exist then. Photo: EU/Copernicus Sentinel

The same island

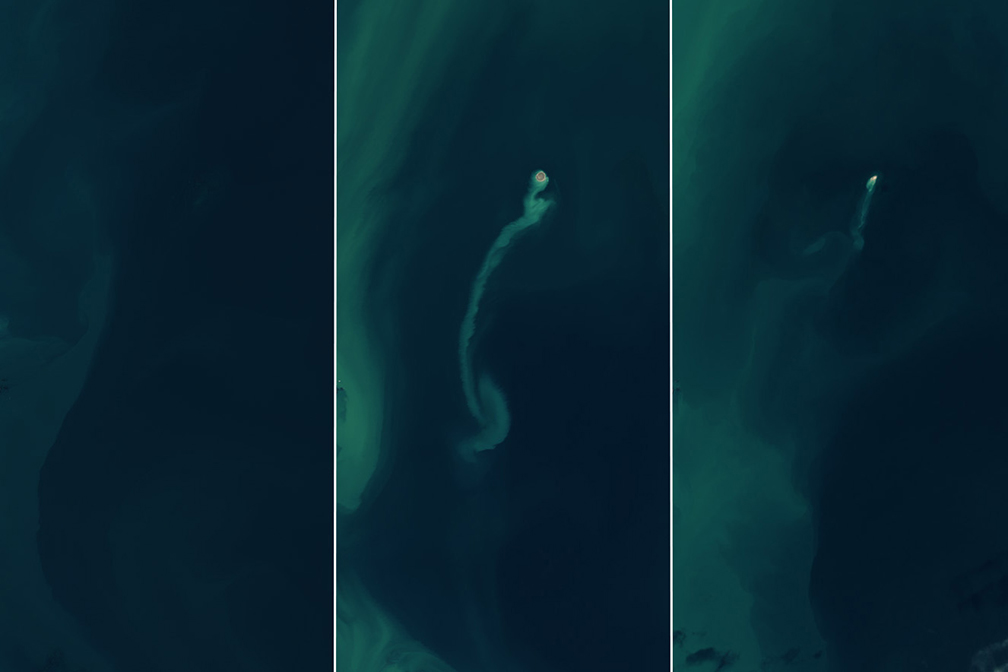

Landsat 8 and 9 orbit the Earth at a distance of about 700km. Designed for geological survey work, it’s no surprise that their engineers pay careful attention to the seismologically excitable Caspian Sea. And in 2023, that attention was rewarded. Where before only empty water had sat, suddenly a speck of dirt jutted above the water line, trailed by a shallow sand bank.This was the same intermittent island that Abikh had recorded in the 1860s. By 2024, Kumani Island was almost gone again.

The reappearance of Kumani came a year after a massive explosion on nearby Dashly Island. Oil rig workers caught the fireball on camera. It made international news, especially given the strategic location of the Caspian Sea.

At the time, Kumani Island still sat under the water 10km away. But the same geological process driving the explosion at Dashly was ready to make its move at Kumani as well.

Not to be outdone by the Gulf of Mexico, there was a massive explosion in the Caspian Sea pic.twitter.com/JgxMkAmzUW

— philip lewis (@Phil_Lewis_) July 4, 2021

Kumani’s short life

Abikh, the geologist who painstakingly charted the islands of the Caspian Sea, also solved the riddle of their existence. He found that irregular outflows of mud sporadically changed the underwater topology. They often erupted explosively above the surface of the water, and so they were called mud volcanoes.

He wasn’t the first to describe them, but he was the first to realize that they clustered along fault lines in the tectonic plates below the water. The mud volcanoes and the dramatic flames that sometimes accompanied them sprang from subterranean friction that forced natural gas, mud, and water to the surface. Soft rock, the world’s largest inland bodies of water, and plentiful natural gas explain why Azerbaijan is home to over half the world’s mud volcanoes.

It’s not clear how exactly some of them explode, but with natural gas involved, it’s no wonder that the government keeps them under strict surveillance.

Azerbaijan is home to over half of the world’s mud volcanoes. Photo: geologyscience.com

Mud volcanoes may exist on other planets

Mud volcanoes result in flashy explosions on Earth, but on Mars, they hint at a possible history of life on the Red Planet. Mounds of mud in the northern lowlands resemble terrestrial mud volcanoes. If that is what they are, then the material near their craters would be drawn from deeper under the ground than normal surface rock.

Given that the Martian surface seems utterly devoid of life, underground is one of the last places left to look for microbes, past or present.

Muddy mounds in the northern lowlands of Mars might be mud volcanoes. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona