This week, alpinist Anatoli Boukreev would have turned 67. One of the best alpinists of the 20th century, Boukreev made hundreds of bold ascents and several incredible speed climbs. He was genuine, full of energy, and loved the mountains. Twenty-seven years after his death, his legacy endures.

Anatoli Boukreev. Photo: Jaan Kunapp

Boukreev, the ‘Easterner’

Anatoli Nikolaevich Boukreev was born on Jan. 16, 1958, in Korkino, Chelyabinsk Oblast, south of the Ural Mountains in Russia.

Despite little money, his parents gave their children everything they could, starting with education, values, and inspiration. When Boukreev was born, his mother named him Anatoli, meaning “from the East, rising sun.”

At twelve, Boukreev became the youngest member of the geology science group of the Young Pioneers, and his interest in climbing started soon after, in the Urals. Thanks to the “Russian school” of mountaineering, he received strict, high-level training. At 14, Boukreev trained on 4,979m Talgar Peak in the Tien Shan Mountains in Kazakhstan.

An outstanding student, Boukreev graduated in 1979 from Chelyabinsk University with a Bachelor of Science in physics. That same year, he became a cross-country ski coach. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, he moved to Kazakhstan, and in 1991 he obtained Kazakh citizenship.

Korkino on Google Earth.

Health problems

Boukreev’s childhood home was close to a nuclear waste site, and the young Boukreev had several health problems: asthma, chronic nephritis, and hypertension. One of his elder sisters died at 35 of cancer. In 1981, Boukreev had meningitis, and later in life, he survived two ugly traffic accidents.

Boukreev realized he had to fight against his health handicaps, so he took training very seriously.

Hundreds of peaks

Between 1981 and 1993, Boukreev summited many 4,000m peaks in the Caucasus and more than 200 peaks between 5,000m and 6,000m in the Pamirs and the Tien Shan.

In 1980, Boukreev summited 7,495m Ismail Samani in the Pamirs and 7,134m Ibn Sina in the Trans-Alay Range. He reached the summit of 7,000’ers 30 times!

Boukreev joined the national mountaineering team and worked as an instructor and high-altitude mountaineering coach in the 1980s and 1990s. He won the Snow Leopard Award four times.

Photo: Anatoli Boukreev

Speed climbing

In 1987, he summited Ibn Sina in a record time of eight hours and needed only six hours to descend to base camp. He won several speed ascent competitions, including on Ismail Samani Peak and 5,642m Elbrus.

In 1990, he summited Denali twice, first via the Cassin Ridge. A few days later, he returned and summited in a record time of 10 hours and 30 minutes.

In the spring of 1984, Boukreev ascended Makalu in 46 hours. One year later, he finished Dhaulagiri I solo in 17 hours and 15 minutes.

In 1996, Boukreev summited Lhotse solo in 21 hours and 15 minutes. In the spring of 1997, he reached Broad Peak’s Central Summit solo in 36 hours. That summer, he summited Gasherbrum II in 9 hours and 30 minutes.

Other notable climbs

In the autumn of 1995, Boukreev summited Cho Oyu solo, self-supported and in alpine style. A few weeks later, he summited Shisha Pangma solo in alpine style.

Anatoli Boukreev approaches Everest’s Hillary Step on May 10, 1996. Photo: Neal Beidleman

In 1989, Boukreev was a member of the Soviet Expedition led by Eduard Myslovsky that summited Kangchenjunga and made a full traverse of the four highest peaks in the Kangchenjunga Massif. During the expedition, Boukreev also reached the top of Kangchenjunga’s Central Peak.

Boukreev summited Dhaulagiri I twice (in 1991 via a new route on the West Face and in 1995). He also climbed Everest four times (1991, 1995, 1996, and 1997); K2 in 1993; Makalu in 1994; Manaslu in winter in 1996; Lhotse in 1996 and 1997; Cho Oyu and Shisha Pangma Central in 1996; Broad Peak’s foresummit and Gasherbrum II in 1997. Whew!

Between 1996 and 1997, Boukreev was especially busy. He summited four 8,000m peaks in 1996 and four more in 1997.

In 1988, he made the first traverse of the Pobeda Massif, covering more than 20km above 7,000m. In February 1990, he reached 7,100m on 7,439m Pobeda but had to abort his ascent to rescue other climbers.

Not keen on bottled oxygen

Boukreev didn’t like climbing with bottled oxygen. On the Kangchenjunga traverse, the team leader ordered all climbers to use oxygen, and on a couple of 8,000m expeditions when he worked as a guide, he also used oxygen. He went without supplemental oxygen on Everest (3x), Cho Oyu (2x), Dhaulagiri I (2x), Lhotse (2x), Makalu, and Manaslu.

In 1997, the American Alpine Journal published an article by Boukreev entitled The Oxygen Illusion, Perspectives on the Business of High-Altitude Climbing.

“The use of bottled oxygen above 8,000m gives only a false security that increases risk by promoting power that masks the symptoms of illness for a time until one runs out of oxygen,” Boukreev wrote. “Guaranteed summits, with emphasis on compensating for poor conditioning in exchange for ever-higher prices, is of questionable morality. We have a very limited rescue potential above 7,500m. It’s simply impossible to rescue any but the minimally debilitated in this environment…That is the sad lesson of commercial mountaineering in 1996.”

You can read his full article here.

Everest 1996

In the spring of 1996, Boukreev was working as a guide for Mountain Madness, led by Scott Fischer. That May, 11 people died on Everest.

On May 10 and 11, a blizzard hit the mountain, and eight climbers couldn’t return to high camp. After summiting, Boukreev descended to a high camp to collect oxygen and warm tea for the struggling climbers. He started back up to save people, despite the storm and with no oxygen for himself. He made several attempts to find the people on the stormy mountain and saved three lives.

This was the famous Into Thin Air disaster. U.S. journalist Jon Krakauer later complained that because Boukreev did not use supplemental oxygen, he could not properly help other climbers. Boukreev defended himself and made counter-allegations, and the dispute continued. The story is well known, with several books and movies about that tragic spring.

Scott Fischer, who died on Everest in 1996. Photo: Wikipedia

Mountaineering philosophy

Despite his competitive nature, Boukreev liked teamwork and had many friends in the mountaineering community.

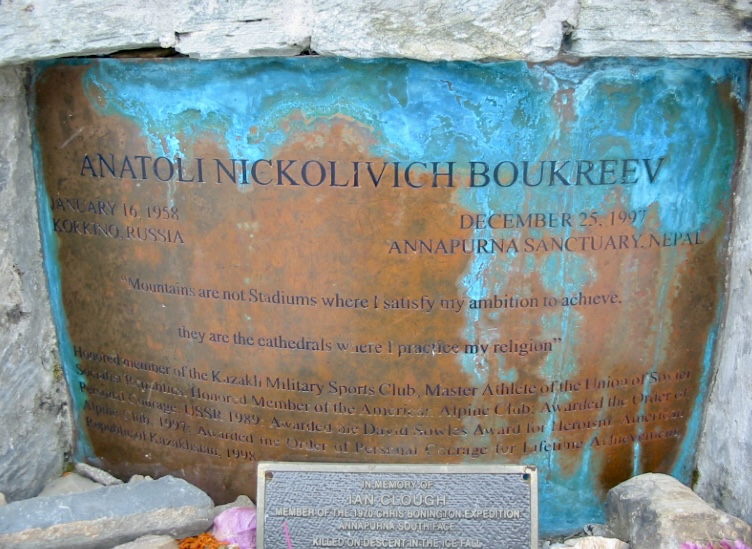

“Mountains are not stadiums where I satisfy my ambitions to achieve,” wrote this informal mountain philosopher. “They are cathedrals, grand and pure, the houses of my religion. I approach them as any human goes to worship. On their altars, I strive to perfect myself physically and spiritually. In their presence, I attempt to understand my life, to exorcise vanity, greed, and fear. In the mountains, I celebrate creation, for on each journey, I am reborn.”

Anatoli Boukreev, left, and climbing partner Vladimir Balyberdin. Photo: Anatoli Boukreev

Death on Annapurna I

In December 1997, Boukreev, Simone Moro, and Dmitry Sobolev attempted Annapurna I via the east face of Fang and Annapurna’s southwest ridge. On December 25, while they were fixing the ropes in a couloir at around 5,700m, a big cornice broke loose from Annapurna’s western wall, causing a huge avalanche that killed Boukreev and Sobolev. Moro miraculously survived.

According to Moro, at 12:15 pm, he saw an ice cornice falling from the ridge at 6,350m, gathering snow as it broke into pieces. The ice and snow avalanche was 50m wide. Moro called out a warning to Boukreev and saw him run to his right to dodge the avalanche. Moro clung to the fixed rope but fell 700m-800m. The fall knocked him unconscious and partly buried him in the snow. When Moro opened his eyes minutes later, he called out but did not receive an answer.

Search and rescue operations were not successful. The deadly avalanche buried Boukreev and Sobolev.

Boukreev was posthumously awarded the Order of Personal Courage by the President of Kazakhstan.

Mount Elbrus. Photo: Anna Efimova

Legacy

Despite all his ascents, Boukreev was humble. In his diaries, Boukreev wrote, “I want to achieve something essential in life, something that cannot be measured by wealth or position in society. I want to respect myself as a man and to earn the respect of my friends and family.”

He died too early, at 39, but his relatively short life was first-class.

“I would rather be a superb meteor, every atom of me in magnificent glow, than a sleepy and permanent planet,” Jack London, one of Boukreev’s favorite writers, wrote.

For much more about Boukreev’s life, we highly recommend Above the Clouds: The Diaries of a High Altitude Mountaineer, collected and edited by Linda Wylie.

Anatoli Boukreev’s memorial at Annapurna Base Camp. Photo: Wikipedia

Below, a short interview with Boukreev after the fatal spring on Everest in 1996.