While filming the BBC Winterwatch television series in Northern Ireland, the crew discovered a dead body.

It was a spider’s dead body, which is not nearly as alarming as other types of corpses, but it nevertheless presented a rather creepy mystery.

The spider was an orb-weaving cave spider, Metellina merianae, found deceased on the ceiling of an abandoned Victorian gunpowder store. A strange location for the reclusive, cave-dwelling spider, but even stranger was the condition of the body.

A crystal-like whitish growth entirely covered the victim’s body, with only the legs sticking out from the pale and jagged fungal mass. Intrigued, the crew photographed the fungus and the spider it had consumed.

They sent the photos and the specimen to Dr. Harry Evans, an expert in fungi. He received the body, which had been carefully air dried in a sterile plastic tube, and set to examining it. A new article reveals the results of his investigation: They had found a new fungi species, one that infected and took over the bodies of spiders.

The film crew found the dead spider on the grounds of this nature preserve and historical site. Photo: Shutterstock

An accidental Victorian import?

Genetic analysis backed up Dr. Evans’ initial observations. His colleague at the Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International, microbiologist Dr. Alan Buddie, sequenced the DNA of the new fungus. He confirmed that it was a unique species of the genus Gibellula and sketched out an evolutionary tree.

The phylogenetic tree placed it in the same family as two species of fungus from Asia. leading to speculation about its origin. Paul Stewart, Manager of Castle Espie, where the gunpowder store is located, proposed that it had come from Asia. During the 19th century, the British Isles engaged in a brisk trade with Asian markets. Could this fungus have entered Ireland over a century ago on gunpowder packaging and flourished in the dark, damp storeroom?

They needed more samples. An Irish caving specialist named Tim Fogg entered two different cave systems in Northern Ireland armed with delicate forceps and sterile collection tubes. He carefully noted the spiders’ locations and then sent them on to researchers. The fungus was present, which confirmed that it had not been imported in the 19th century but had been in Ireland for far longer than that.

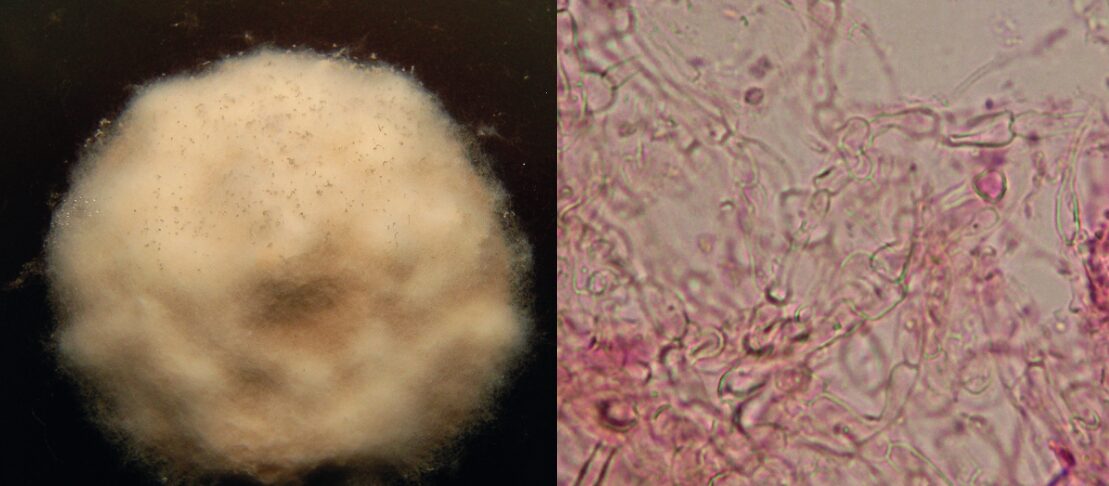

Left, a colony of Gibellula attenboroughii, grown in the lab. Right, the same mold under a microscope. Photo: Evans et al.

Gibellula attenboroughii

At first, the new fungus was humorously known as Gibellula Bangbangus, in honor of the gunpowder storeroom. But ultimately, it received a new name, Gibellula attenboroughii, after legendary BBC presenter Sir David Attenborough. Without his work, the nature program that found the fungus would likely never have existed.

This is not the first species named after David Attenborough. Previous examples include a Peruvian frog, a long-beaked echidna, an Indonesian weevil, and a tiny marsupial from Australia’s early Miocene.

The fungus is certainly novel in other ways, however. It doesn’t just grow on its hosts, the cave-dwelling Irish orb-weaver, and its close relatives. It also controls them. Once infected, the spiders were swallowed up by a mass of fungus, growing out in thin tendrils and spikes. The fungus then changed the behavior of the hosts in order to propagate itself.

Usually a reclusive creature hiding in dark corners and waiting for prey, the cave spiders were forced to move, minds and bodies overcome by the invader. They were driven out into the open and allowed to die. The fungus then began releasing spores into the open air.

This blob of fungal slime completely covers the long-dead spider host. It was found out in the open, on a cave wall. Photo: Evans et al.

More zombifying fungi out there

The spiders were found dead on open ceilings and cave walls and even, perhaps, on a patch of moss beside a Welsh lake. A dead Metellina merianae spider turned up on the shore of Lake Vyrnwy in Wales in 2016, covered in fungus and exposed to the open air. Researchers now believe this, too, was Gibellula attenboroughii.

The spider fungus of the British Isles, the new study argues, has been long neglected. This new discovery shows that more work is needed to understand the variety and extent of the fungal infections in British and Irish spider populations. Spiders are key to the ecosystem, and so their health is vitally important. Especially since more undiscovered Gibellula species likely exist.

A pair of dried specimens infected with the fungus. The large spider at left is Meta menardi. On the right, its smaller relative, Metellina merianae. Photo: Evans et al.

Perhaps the most intriguing question to pursue, however, is how the fungus works. The fungal infection forces the spiders out into the open, but it isn’t clear how it does so. The infamous cordyceps fungus, which infects and controls Amazonian ants, works by taking control of the body, leaving the mind terrifyingly unaltered. Is this what is happening to scores of shy Irish orb-weavers? Is the fungus triggering hormonal changes that alter behavior?

We are left with unknowns. How are the spiders being controlled? Perhaps more importantly, just how widespread are these understudied arachnid fungi? For now, we can only be grateful not to be orb-weaving cave spiders.