Archaeologists exploring a neglected corner of the Valley of Kings in Egypt have identified the tomb of an Egyptian pharaoh of the New Kingdom. This marks the first such tomb found since 1922 when the discovery of 19-year-old pharaoh Tutankhamun’s burial chambers enraptured the world.

The inhabitant of this tomb has a lower profile. Pharaoh Thutmose II ruled for only five years until his death at age 30, when he fell victim to a disease that left him scarred and shriveled. His half-sister and widow, Hatshepsut, assumed the throne as his regent. As Egypt’s second-known female pharaoh and an influential stateswoman, her legacy far outshone his.

Now Thutmose II is back in the spotlight.

A hidden tomb

Limestone debris clogged the staircase into the tomb. Photo: Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities

In 2022, a joint Egyptian-British expedition found traces of a staircase leading into the stony depths below a monumental cliff. After months of excavation, they cleared the passageway of rocky debris and emerged into a stark, empty tomb.

There was no sarcophagus or any of the offerings traditional to Egyptian burial sites. Instead, huge limestone chunks clogged the hallways, just like the staircase. But above it all, the ceiling shone with painted stars, and the walls showed scenes from the book of Amduat, reserved for the burials of kings. This had been the tomb of a pharaoh.

So where was he?

Fragments of the old tomb

Scattered among the limestone debris, a few broken fragments of alabaster memorialized the name of the tomb’s inhabitant: Thutmose II. Others bore the name of his widow, Hatshepsut.

The debris everywhere didn’t align with grave robbers, the common reason for empty tombs. This looked like an orderly evacuation following some sort of disaster. The team concluded waterfalls had pummeled the base of the cliff and flooded the tomb, probably only five or six years after the burial.

But whoever had moved Thutmose II’s remains hadn’t done so immaculately.

“And thank goodness they did actually break one or two things,” commented Dr. Piers Litherland, the lead archaeologist on the team, “because that’s how we found out whose tomb it was.”

Several fragments of alabaster jars inscribed with the names of Thutmose II and Hatshepsut revealed the inhabitant’s identity. Photo: Egypt State Information Service

Where was Thutmose II moved?

Egyptologists have known where Thutmose II’s body was since 1881. Entombed alongside other royals in the Royal Cache at Deir el-Bahri, Thutmose II had been moved to this communal crypt about 500 years after his death, along with those whose own tombs had also disintegrated.

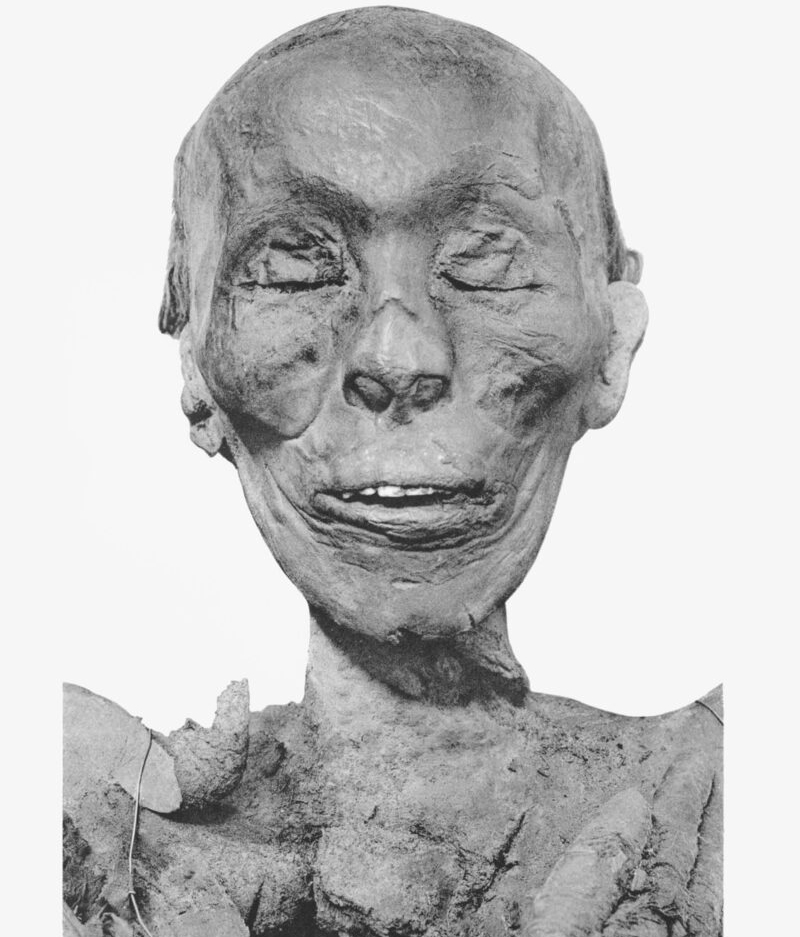

The French Egyptologist who unwrapped Thutmose II’s mummy wrote, “He resembles [Thutmose I, his father], but his features are not so marked and are characterized by greater gentleness. He had scarcely reached the age of thirty when he fell victim to a disease of which the process of embalming could not remove the traces.”

The face of the mummy believed to be Thutmose II shows signs of disease. Photo: University of Chicago

But if a flood destroyed his tomb a handful of years after his death, a second tomb would have had to house his remains and burial gifts for the intervening 500 years before his body wound up in that communal site. If archaeologists can find it, the artifacts within might cast more light on Thutmose II’s brief and poorly documented reign.

Hatshepsut, his more famous widow, also stands to benefit should Thutmose II’s second tomb be located. Her successor, Thutmose III — son of Thutmose II by a minor consort — set to erasing every record of her reign following her death. His motivation was likely revenge over her long reign, which prevented him from taking the throne.

Thutmose II’s burial artifacts may contain information on both his reign and the early life of one of Egypt’s most iconic but mysterious pharaohs.