Before it shut down in 2022, a telescope in Chile captured one final gift for the world that has just been released: the universe’s baby photos, just 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

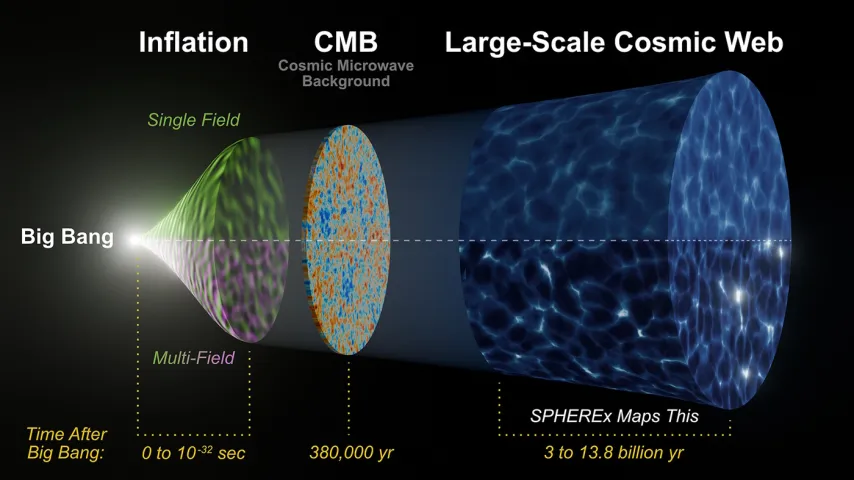

These freckled photos of the early universe, at an instant known as the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), are the farthest back in time we can look. Observing the Big Bang or immediately after is not possible, and not just because of technical limitations.

Before the epoch shown in these images, the universe was so dense with plasma that light couldn’t travel for more than a fraction of a millimeter without scattering off a proton or an electron. Everything just looked like a dense fog. Then the universe cooled enough to allow those charged particles to fuse into hydrogen and helium. Space opened up and became visible. The last photons from those first visible moments were preserved.

The photons set off through space. All of them were stretched by the expansion of space around them. Some became further stretched out by gravitational wells around galaxy clusters. Others received an energy boost. The patterns of the evolving universe imprinted themselves on these ancient photons.

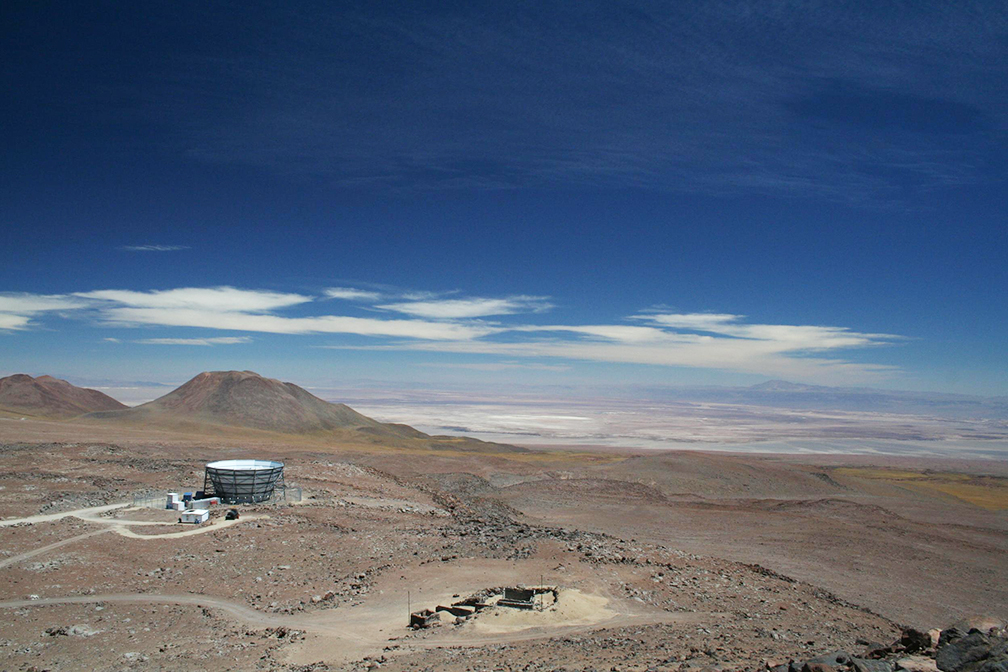

Almost 14 billion years after their liberation, some of them hit the smooth white surface of a radio telescope located in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile.

The Atacama Cosmology Telescope was decommissioned in 2022. Several next-generation cosmology telescopes will take its place. Photo: ACT/Princeton

Last observations

The Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) is now closed for business. After 15 years of productive data releases, it saw its final light in 2022. However, the ACT team only recently released the polished versions of the telescope’s last observations.

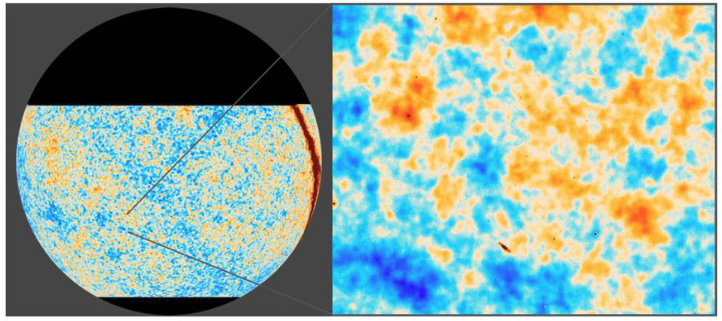

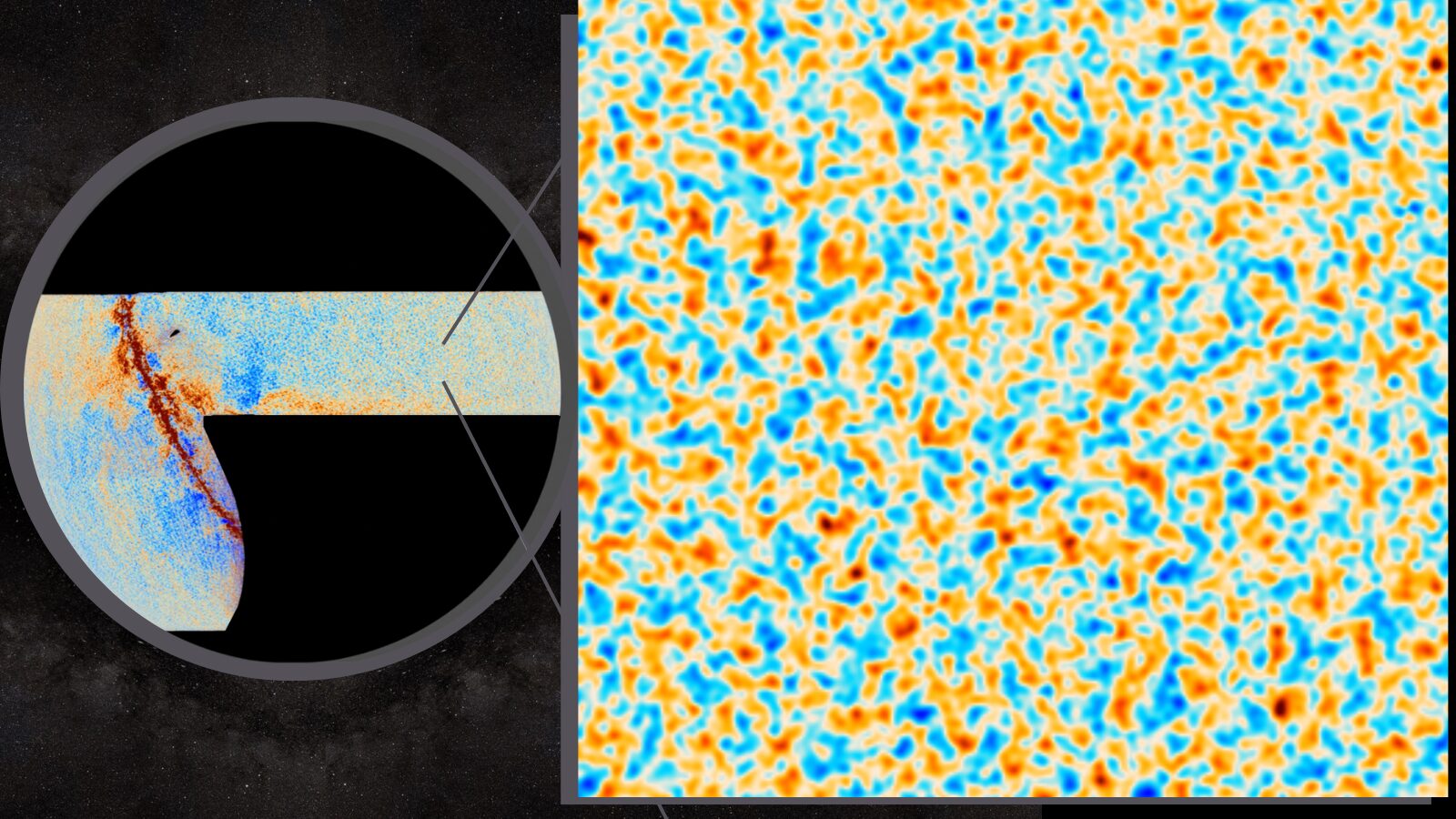

These images not only show the most precise, high-resolution observations of the Cosmic Microwave Background but they also cover more of the sky than ever before. The red and blue speckles represent regions of over- and under-densities — places where, 14 billion years ago, the universe had just a little more or less plasma.

The new images confirm previous observations that the structure in the early universe maps onto its modern structure. Where there were slightly more photons in the primordial plasma now sit the most massive galaxy clusters. Fewer, and there’s empty space.

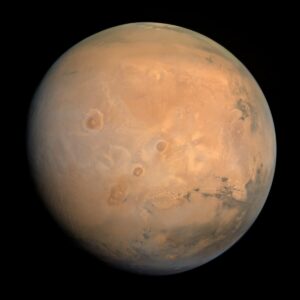

Regions of high density in the early universe map onto galaxy clusters in the present day. Photo: Caltech/IPAC/Robert Hurt

So far, general relativity holds up

Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which predicts how matter and light interact with one another at large scales, is one of the best substantiated theories in modern physics. It also causes problems.

There appear to be four fundamental forces in nature: gravity, electromagnetism, weak, and strong. One set of physical laws known as the Standard model cohesively describes electromagnetism, the strong force, and the weak force. Gravity, though, has proven hard to mesh with the others.

Discovering that general relativity isn’t quite accurate is the grand hope of those searching for one theory of physics that unites all four forces. Perhaps then, a new model of gravity will appear out of the cracks, one that slots nicely into the Standard model.

But general relativity has triumphed repeatedly so far, and the latest images from the ACT are no exception.

“The amount by which light bends around dark matter structures is just as predicted by Einstein’s theory of gravity,” cosmologist Mathew Madhavacheril told Penn Today.

How polarized light fits in the early universe

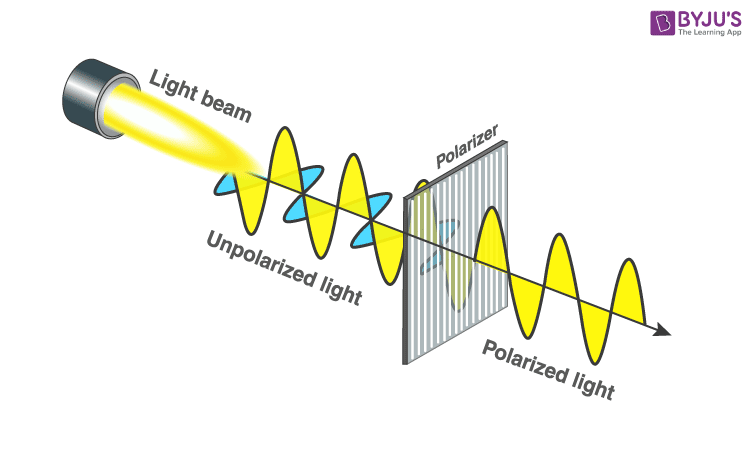

Perhaps the most important part of these new observations is the detailed polarimetry. Polarimetry describes the measurement not just of how much light there is, or how much energy that light has, but in what direction the light is vibrating. Natural light is unpolarized, meaning that light waves traveling toward us may vibrate in any direction perpendicular to the line of travel.

It’s easy to change that by sticking a thin grating in front of the light, only allowing one vibrational direction through. That’s how polarized sunglasses work.

A polarizer only transmits light that vibrates in one direction. Photo: BYJU

The polarization signal in the CMB sits at barely detectable thresholds. But ACT’s new observations push past that threshold, and unlike the handful of other telescopes in the polarization game, they cover most of the sky.

Polarization goes beyond the effects of gravity from massive structures like galaxies. Microscopic quantum density fluctuations can alter the polarization of light.

Einstein’s formulation of general relativity does not describe the quantum world. In fact, Einstein was uncomfortable with quantum mechanics and encouraged its proponents to better address its many peculiarities. While this leaves room for future physicists to etch their name in history, it would be a lot simpler if Einstein had just figured out everything for us.

He didn’t. General relativity on the quantum (read: atomic) scale continues to confound us, not least because testing it in the lab is fiendishly difficult.

Fortunately, the new ACT data release is precise enough to contain clues about quantum gravity in its polarimetry. We just have to decode them.

The new polarimetry measurements of the Cosmic Microwave Background may enlighten us about quantum gravity. Photo: ACT/Princeton