The mystery surrounding a recent Nepalese-Chilean expedition to, let’s say, a certain peak in Nepal’s Kangchenjunga region has kept both researchers and this writer busy. Finding out exactly which peak the team climbed has not been easy.

The good news is that we finally have an answer. The not-so-good news is that the peak is not what the climbers thought they climbed. But the team has made a meritable first ascent nevertheless.

The expedition outfitter Xtreme Climbers released a preliminary report on what was supposedly the first ascent of Sharphu IV, part of the Sharphu group of six peaks. The account featured inaccuracies and contradictions about Sharphu IV’s supposed altitude. That wasn’t the climbing team’s fault. Rather, the list of peaks on Nepal’s Ministry of Tourism website is hopelessly confused in this case.

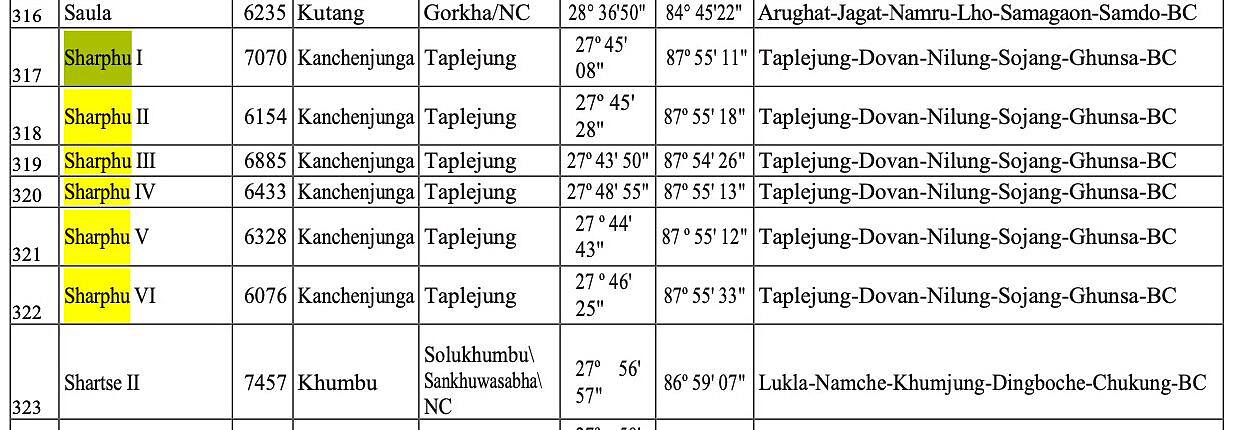

Previous expeditions faced the same confusion because of the wrong altitudes and the little information available about that remote region. Apparently, the Ministry has changed the altitudes and positions of the Sharphu peaks more than once as they updated their lists. The entire 2024 list is here, but for simplicity, consider just the Sharphu section reprinted below.

A fragment of the list of peaks by Nepal’s Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation, edition 2024.

No GPS data

Asked by Explorersweb, Xtreme Climbers did its best to provide further details. Rodolphe Popier, 8000ers.com’s expert researcher, weighed in, and we also consulted The Himalayan Database.

Pemba Sherpa, the outfitter’s managing director, was positive that the peak they climbed was Sharphu IV. However, he admitted that their client’s Garmin device was not working correctly, so GPS data couldn’t confirm exactly where they were.

Pemba explained that the team flew from Kathmandu to Bhadrapur, then drove by Jeep to Sekathum and beyond to Ghunsa-Sharphu Base Camp at 4,610m.

The four-person team consisted of Lhakpa Chhiri Sherpa (Nepal), Ngada Sherpa (Nepal), Hernan Leal (Chile), and Purnima Shrestha (Nepal). For acclimatization, they rotated three times up to higher camps before the final push between March 23 and summit day on March 25.

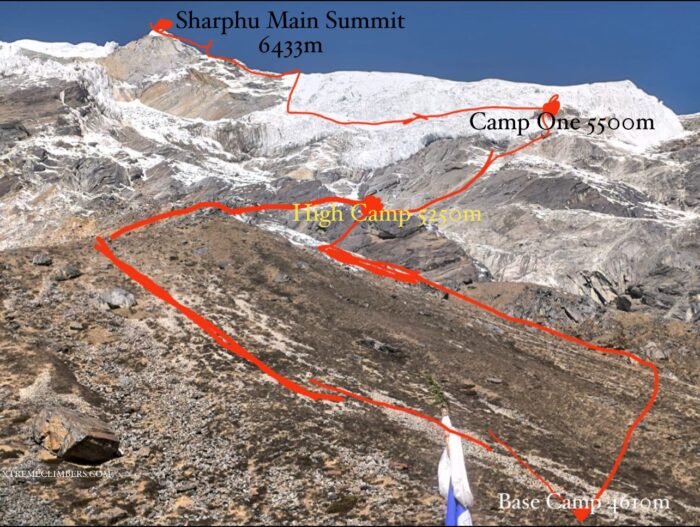

Everyone was elated at what they considered a first ascent. They also forwarded a topo of the climb, below.

Topo provided by Xtreme Climbers, with the peak and the route. Note that the summit does not feature a number. Photo: Xtreme Climbers

The topo just marks the top as “Sharphu Main Summit 6,433m.” However, contrary to Nepal’s Peak Profile website, the only Sharphu peak that reaches 6,433m is not Sharphu IV but Sharphu I. The altitudes are more reliable in other sources, such as previous teams’ reports and The Himalayan Database (THD). Here, the peak identified as Sharphu IV is 6,172m and was first climbed in 1962 by a Japanese team led by Sasuke Nakao.

But that is not the end of the story.

Sharphu what?

Rodolphe Popier told ExplorersWeb that the climbers’ own topo shows that they ascended not Sharphu IV but Sharpu VI (6,076m).

Popier points out that the 2025 team’s pictures also support this. The summit, which they indicated on the photo below (labels added by Popier), is actually Sharphu VI.

Sharphu II and Sharphu VI. Photo: Xtreme Climbers/labels by Gunter Seyfferth

So, where is Sharphu IV compared to the other peaks of the group?

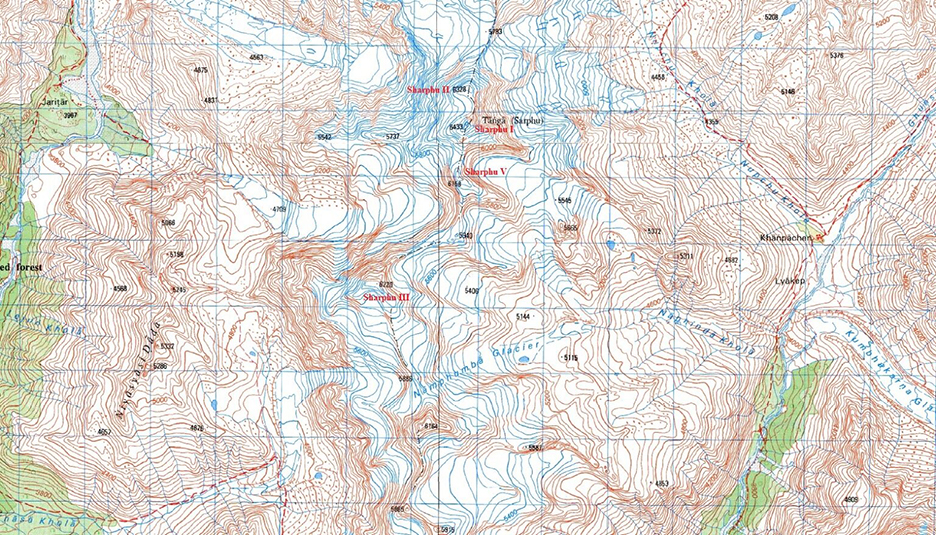

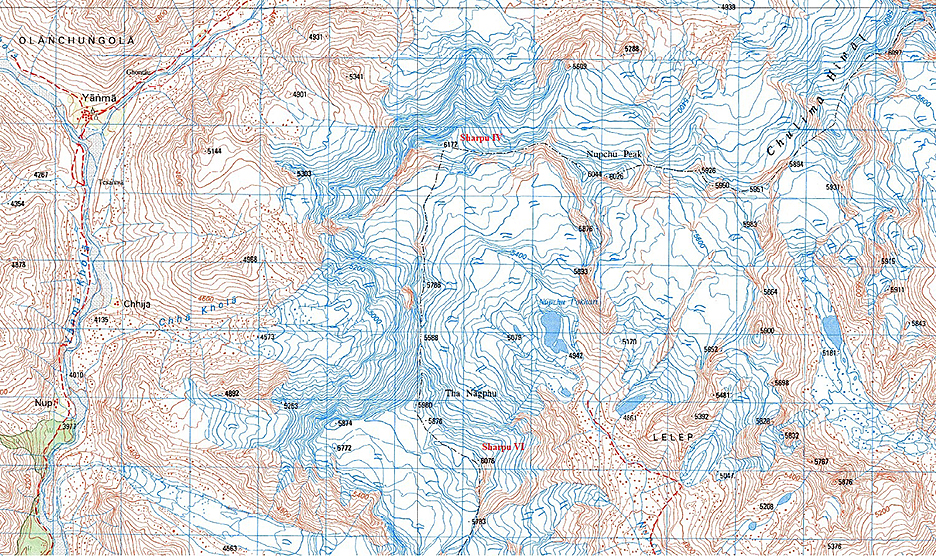

Here is the correct order of the peaks on a map, as sorted out by The Himalayan Database:

The Sharphu peaks I, II, III, and V.

The mistaken peaks, Sharphu IV and Sharphu VI.

Summit pictures show a distant Sharphu IV

Ironically, Shaphu IV can actually be seen in the background of the 2025 team’s summit picture.

Location of Sharphu IV (SPH4) according to Rodolphe Popier, from the team’s summit picture. Photo: Xtreme Climbers

Still a first ascent!

According to THD, Sharphu VI has been attempted only once, and rather recently, by the Japanese Himalayan Camp team led by Takahiro Kaneko in 2023. Their plan was to climb Sharphu VI and then Sato Peak. As they reported to THD, they never summited Sharphu VI: “Abandoned at 6,000m due to impassable crevasse,” they noted.

It seems clear that the recent team wasn’t trying to deceive; their understanding was simply based on inaccurate or confusing official lists. They paid a permit for Sharphu IV. Luckily, without realizing it, they ended up atop another unclimbed peak so they can claim a first ascent.

It remains to be seen what the official summit certificate from the Department of Tourism will call the peak they climbed and what altitude it will indicate.

Mistakes are common

No one mistakes Everest or Ama Dablam, of course, but rarely climbed peaks in remote areas are easy to confuse. The Sharphu group, in particular, has baffled the few teams that have visited the area since the 1960s. Different altitudes assigned to the same peaks have been one of the main sources of confusion.

Many of these altitudes were registered decades ago and may be inaccurate compared to modern systems of measurement. It is especially important for climbers, outfitters, and tourism authorities to correct the altitudes of peaks, especially the unclimbed ones since they will draw the most attention in the future.

A final note: According to the Himalayan Database, Sharphu IV is also called Nupchu Peak. Eberhard Jurgalski of 8000ers.com believes that Sharphu IV, which is slightly separated from the rest, should not be considered part of the group and identified solely as Nupchu. And one more fact: The Japanese team that climbed Sharphu IV in 1962 (according to THD) was also mistaken. They thought they were climbing Ohmi Kangri.