While Egyptian kings and queens are the most famous examples of mummification, the practice wasn’t just for pharaohs. It expanded over time until everyone from the poor up were being preserved for eternity.

So, where are all the mummies? Well, unfortunately, 700 years of rich Europeans ate them. For their health, of course.

From a 12th-century translation error, a massive trade kicked off, depopulating the tombs of Egypt to populate European apothecaries -– and starting an underground market in fake mummy powder.

Bitumen and mūmiyah

Why did Europeans think that eating mummies was a good idea? It’s all to do with bitumen. Bitumen is a viscous petroleum product, which occurs naturally in a semi-solid form. Bitumen is particularly common around the Dead Sea, and is useful for waterproofing and as a glue. Archaeological evidence shows that both early humans and their Neanderthal cousins used bitumen tens of thousands of years ago. It even appears in the Bible as the mortar which was used in the tower of Babel.

By the classical era, bitumen was used in everything from shipbuilding to jewelry. People also started using it as medicine. Pliny the Elder, a Roman author and naturalist, lists 27 discrete medicinal applications for it. These include staunching blood flow, diagnosing epilepsy, treating leprosy, dysentery, and gout, and curing toothache.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Muslim scholars took pains to preserve classical learning. By the Middle Ages, Arabic authors were considered the foremost medicinal experts throughout Europe and the Middle East. The tradition of using bitumen as medicine continued through the works of scholars like Avicenna, who prescribed it for concussions, paralysis, and more. He didn’t call it “bitumen,” though. He called it mūmiyah, from the Persian word mum, meaning wax.

According to the Bible, the Tower of Babel was built using bitumen. If there is one thing I know about building materials, it’s that it is also good to eat. Photo: Pieter Brueghel the Elder per Wikimedia Commons

A medieval game of telephone

The Ancient Egyptians didn’t use bitumen for their mummies. However, the dark resin they used resembled bitumen, leading many classical and medieval observers to believe that bitumen coated Egyptian mummies. So the same word came to refer both to naturally occurring bitumen and the dark waxy coating found on Egyptian mummies.

In the 12th century, an Italian translator of Arabic texts named Gerard of Cremona came across Rhazes of Baghdad’s reference to mūmiyah. Gerard said the product was created when “the liquid of the dead, mixed with the aloes, is transformed and is similar to marine pitch.”

Another European, Simon Geneunsis, translated a work by Arab physician Serapion the Younger that referenced medicinal bitumen as “mumia.” Geneunsis interprets the word along the same lines as Gerard of Cremona, calling it “the mumia of the sepulchers,” which is formed when the aloes and spices used to prepare the dead mix with the liquids the corpse itself expels.”

Meanwhile, crusaders were bringing back the bitumen medicine fad from the Islamic medical traditions of the Middle East. Unfortunately, the easily accessible supplies of bitumen in the area were limited. Shrewd Alexandrian merchants realized that there was all this mumia lying around, coating the bodies of the dead. They began raiding tombs, breaking the resinous bodies up, and exporting them to Europe.

The fact that the mumia came from corpses didn’t bother people much, possibly due to the confusion between medical mumia and Egyptian mummies. Before long, mumia stopped being the substance on the mummy and became the mummy itself.

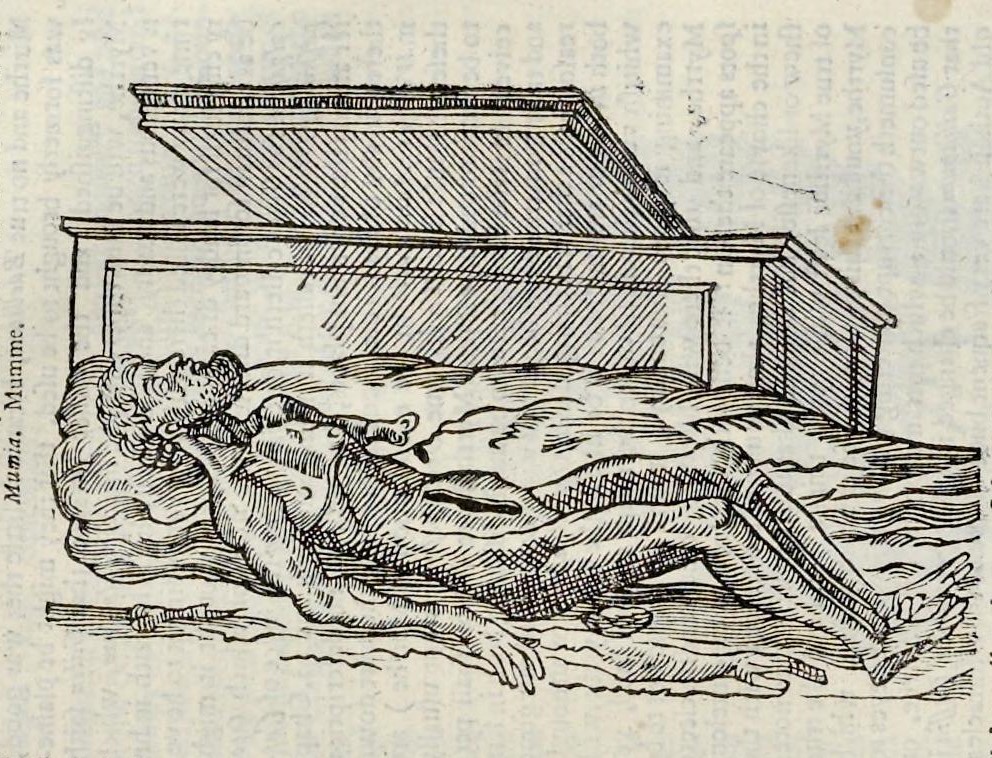

The blackened, waxy appearance of many mummies led observers to conflate them with the black and waxy bitumen. This mummy is one of over 100 held in the British Museum. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

It’s good for what ails you

Mumia became a wildly popular remedy in Europe, sold in every well-stocked apothecary. One influential pharmacopeia, Theatrum Botanicum, contains a long list of conditions mumia is useful for, including headaches, colds, coughs, seizures, heart problems, poisoning, scorpion stings, snake bites, bladder ulcers, paralysis, and retention of urine. Treatments involved combining mumia with other ingredients, usually a liquid like wine or goat milk.

Genoese physician Giovanni da Vigo considered mumia an essential medicine for ship’s physicians and village doctors. He claimed it promoted wound healing and staunched bleeding. Sir Francis Bacon, the eminent English philosopher, and the physicist Robert Boyle, both considered it useful for wounds, falls, and bruises.

The French king, Francis I, was a habitual mummy consumer; contemporaries reported that he always carried a mixture of rhubarb and mumia on his person, just in case. Nicasius Le Febre, chemist to England’s King Charles II, recommended mummy from Libya specifically.

By the way, if you were wondering how it tasted, the English College of Physicians has the answer. Mummy was listed in their official pharmacopeia from 1618 to 1747, where it is described as being “somewhat acrid and bitterish.”

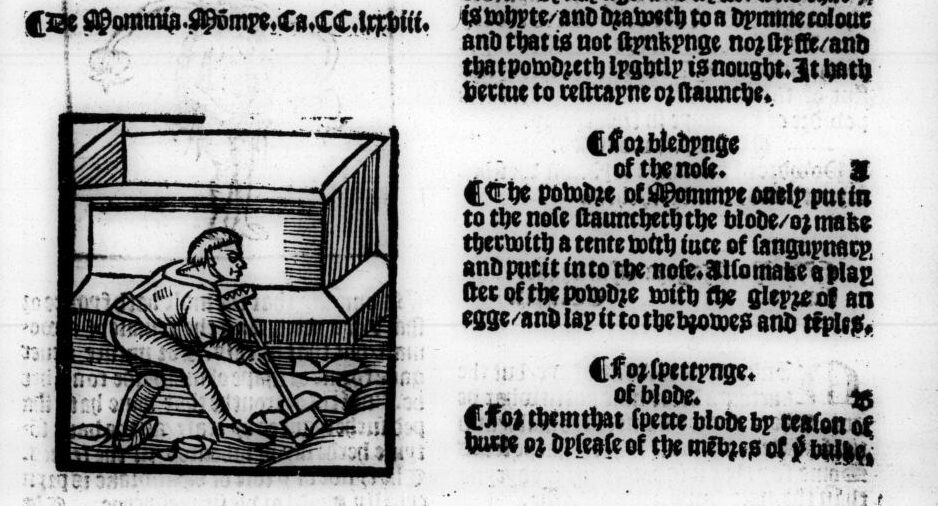

A 1529 herbalism guide shows a man digging up a grave beside text explaining the many medical uses of mummy. Photo: ‘The grete herball,’ 1529

Supply chain issues

Egyptian authorities were not actually keen on all the grave robbing and corpse exporting that was happening. In 1428, authorities in Cairo captured and tortured several people connected to a mummy scheme. They confessed to robbing tombs, boiling the mummified bodies in a pot, and selling the oil which rose to the surface.

It was illegal to export Egyptian mummies out of Egypt. But enforcement could be lax, especially if you had money to grease the wheels. Englishman John Sanderson visited Egypt in 1586, where he explored a sepulcher and broke off chunks of blackened mummified flesh. He applied the correct bribes and compliments, and sailed off with 600 pounds worth of “divers heads, hands, arms, and feete.”

For every literal boatload of real pillaged mummies, there was at least an equal measure of mummies created specifically for export. Many mummy sellers in Egypt found it was easier to source fresh corpses and dry them than it was to dig up old ones. These fresh corpses mostly came from executed criminals, plague victims, and enslaved people.

The Italian traveler Ludovico di Varthema wrote about the local production of mumia during a visit to the Arabian Peninsula. According to him, there were two kinds; the first was made from the dried-up remains of people who had died recently while crossing the desert. The other, nobler and more pure kind, was “the dryed and embalmed bodies of kynges and princes.”

In truth, even authentic mumia wasn’t made from rulers, but from their subjects. European nobles liked to imagine their healthful powder came from ancient priestesses and kings, but the remains of the poor were far more plentiful and accessible.

Digging mummies up was more work than just making them. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Paracelsus and domestic mummy manufacture

Though a fair amount of the mummy product on the market was inauthentic, the real stuff was still being sold into the modern era. One recent study analyzed the contents of an 18th-century pharmaceutical jar labelled “mumia.” They found that the contents really were the remains of an Egyptian mummy from the Ptolemaic period.

But without our modern analysis tools, the question of mumia authenticity was an ongoing problem for physicians. As the supply became more questionable, some medical authorities began to wonder whether mumia being “authentically Egyptian” was even important.

Some definitions of mumia dropped the ancient Egyptian element entirely, ascribing benefits to any old preserved human flesh. The influential physician Paracelsus, who spawned a legion of followers, believed the medicinal benefit of mumia came from a transfer of life energy. To make his mumia, he left a fresh body out exposed. The best bodies were of young, healthy men who died suddenly. Other recipes in this line were even more specific, preferring a 24-year-old redheaded man who was recently executed.

There was a persistent belief that there was a vital animating force remaining in corpses, and one could benefit from this force by consuming corpse products. In the time of Paracelsus, for instance, executioners would collect and sell the blood of those they executed. People believed that drinking it promoted general health and cured epilepsy. Bandages soaked in human fat were applied to wounds, and powdered human skull was prescribed for headaches.

The broader genre of corpse medicine is beyond the scope of this article, but suffice it to say that mumia wasn’t always the only human-derived medicine available.

One recipe for mumia involved emptying the stomach and filling it with herbs, bitumen and other materials, as pictured here. Photo: ‘Theatrum Botanicum,’ John Parkinson, 1640

Some reasonable concerns

Now I’m not a doctor, but I feel confident in saying that “you should eat powdered human corpses for nosebleeds” is not best practice. By the 16th century, many doctors were starting to think along the same lines.

Ambroise Pare, surgeon to four French kings, published a 1582 treatise decrying the use of mummy. He argued that most mummy sold was actually manufactured in France from the recently dead, and also didn’t work. In his professional experience, it had not only failed to stop bleeding but had unsurprisingly caused the patient to have an upset stomach and bad breath.

Pare’s German contemporary, Leonhart Fuchs, made similar arguments. He also laid out the series of medieval translation errors which had led to the idea of mumia. Fuchs decried the “stupid…credulity of certain doctors of our age,” who still prescribed mummy.

Additionally, some commentators were beginning to recognize the historical and cultural wealth that was being ground up for tinctures. English natural philosopher Thomas Browne opined that “The Ægyptian Mummies, which Cambyses or time hath spared, avarice now consumeth. Mummy is become merchandise, Mizraim cures wounds, and Pharaoh is sold for balsams.”

There was also cannibalism. Michel de Montaigne, a 16th-century French writer and early critic of colonialism, pointed out the hypocrisy of demonizing cannibalistic practices in the New World while taking medicinal human flesh at home. But most people didn’t think of it as cannibalism, any more than people today would consider a blood transfusion cannibalism. Mumia wasn’t food, it was medicine.

Still, as time went on, people were increasingly wondering if it was medicine they should be taking. Mumia mania peaked in the 18th century, but took much longer to fade entirely.

Mumia, found in the basement of a German museum. Photo: Hardy Funk/Deutches Museum

Consuming Egypt

For wealthy Europeans, part of the appeal of mumia was the mystical, exotic associations. For centuries, Europeans treated the bodies of deceased Egyptians with a combination of fetishistic fascination and blatant disrespect. They were curios and collectors’ items, souvenirs of exciting trips turned household decor.

Mummy unwrapping parties were popular in 19th-century Europe, where middle and upper-class men and women would watch a mummy’s bandages be unwound, revealing its body as the finale of the morbid show.

The remains were consumable as a variety of commercial products. A popular paint color from the mid-18th to 19th centuries was “mummy brown.” This pigment was made from ground-up mummified bodies. Art historians believe this rich, warm brown pigment appears in a number of well-known paintings, including Eugene Delacroix’s famous Liberty Leading the People. The last tube of mummy brown was produced, unbelievably, in 1964.

There are also accounts, of varying reliability, that both human and animal mummies were used as fertilizer, paper (from their bandages), and fuel for locomotives. These claims are likely exaggerated, but they speak to the manner in which mummified Egyptian remains were treated at the time. As Imperial plunder, they were, literally, things to be consumed.

This painting from the late Victorian era shows a common scene from the period: a group of curious upper-class Europeans observe a mummy being unwrapped. It is unknown whether mummy brown was used in this painting, but its rich, warm browns suggest the possibility. Photo: Paul Philippoteaux via Wikimedia Commons

The end of the mummy-eating era?

By the end of the Victorian period, mumia had fallen out of popular use. But it was still available for sale, and occasionally prescribed, into the beginning of the 20th century. The last known appearance of the drug for sale is in a 1908 Merck catalogue. The German pharmaceutical advertised, “Genuine Egyptian mummy as long as the supply lasts, 17 marks 50 per kilogram.”

Rich old Europeans didn’t actually eat up all the mummies. Archaeologists are still finding them, for one. It’s impossible to say how significantly the manufacture of mumia impacted the number of surviving mummified remains. It’s safe to say, though, that nearly a millennium of looting Egypt led to the loss of untold historical and cultural knowledge.

The 1908 example is troublingly recent, but we might still be tempted to dismiss mumia as something from another, less enlightened age. Exporting ground-up mummy to eat as a health supplement is something so patently absurd that a modern reader might make the mistake of smugly holding themselves above all those involved in the practice.

It’s true that we don’t eat mummies anymore. But physical and cultural wealth is still extracted from exploited nations for the consumption of the global north.

Most human bones available for sale in the West, as curios or medical teaching tools, come from India, though the export of human skeletons was officially banned in the 1980s. World-class museums still display cultural artifacts and remains of colonized people for the predominantly white public to gawk at. Mummy remains merchandise.