The average home — manor, farm, or otherwise — contains only the skulls which are still attached to living inhabitants. This is almost certainly true of your home, at least. (If not, well, get in touch.)

But scattered across the British countryside, otherwise unassuming manor houses and ancestral halls keep human skulls on display. They have to keep them on display, you see, because otherwise the skulls will start screaming.

If you’re cold, they’re cold. Let them into your Elizabethan-era manor house. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Bettiscombe Manor

Bettiscombe is an old manor house in Dorset, built on an ancient site in a small, quiet village. It is known for its gardens and its screaming skull. “Screaming skulls” are human skulls that scream, rattle windows, call forth curses, and otherwise cause bad luck and supernatural mischief when displeased. The chief method of displeasing them is to not put them where they like to be kept.

No one is sure when the Bettiscombe skull arrived at the manor. However, by the time stories began appearing in the 19th century, it had reportedly been there for as long as anyone could remember. It was kept in the house because the other residents claimed it would scream if it was buried in the churchyard.

There was a widely accepted origin story. The skull belonged to an enslaved black man who had died in the house, begging for his body to be sent back to his native land. The owner of Bettiscombe, a member of the Pinney family, instead had him buried in the churchyard.

Immediately, screams began sounding through the house at all hours. Pinney dug up the man’s remains, but instead of returning him as he’d promised, he set the man’s skull up in his house. This was apparently good enough; the haunting ceased. Whenever anyone tried to bury the skull, it started back up again.

It’s a rather terrible story. Luckily, it isn’t true. In 1963, a Pinney descendant sent the skull to the Royal College of Surgeons. Dr. Gilbert Causey declared that it was the skull of a young woman. The Pinneys now believe it belongs to the Iron Age Celtic settlements behind the house. Nevertheless, they think it best to keep it inside the house.

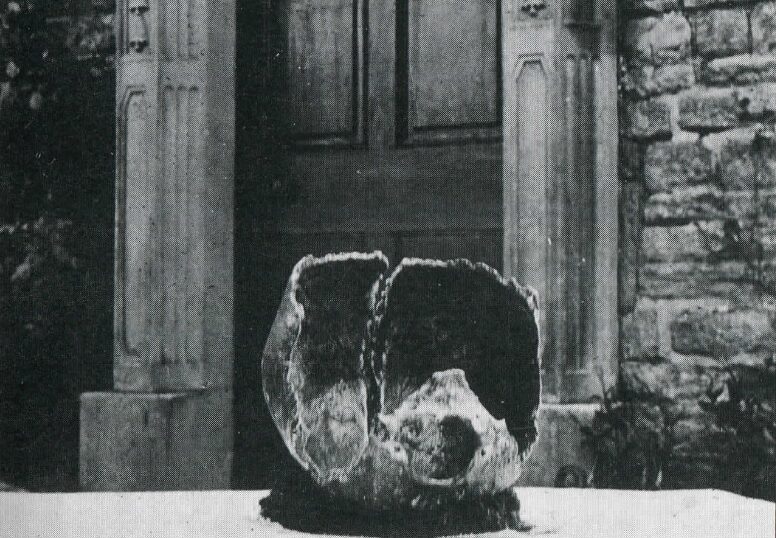

A postcard of Bettiscombe screaming skull. Photo: Victoria and Albert Museum

Tunstead Farm

One skull, which long resided on the windowsill of a lonely Derbyshire farmhouse, became a beloved local character in the late 19th century. The skull was called Dicky or Dickey, and when exactly it came to reside at Tunstead Farm is a matter of pure speculation.

The earliest published account of a skull named Dicky living at Tunstead Farm is from 1809. John Hutchinson wrote about his travels in the Peak District, including an encounter with Dicky. Hutchinson visited the house and saw the skull on the windowsill and interviewed the farm’s owner, Adam Fox. Fox had been raised in the house and claimed the skull had been there for at least 200 years.

Interruptions to that residence produced terrifying disturbances, like ghostly screaming. In general, Fox said, the skull was a sort of guardian. But when it was removed, even temporarily for planned repairs, “There was no peace! no rest! It must be replaced!”

Stories of these incidents are numerous and mostly hearsay. One, for instance, goes that Dicky was thrown into a local reservoir, but had to be removed when all the fish suddenly died.

There are plenty of stories about Dicky’s origin. None of them is particularly likely. Interestingly, as Hutchinson noted, most stories imagined that the skull belonged to a woman, though the skull was invariably referred to in masculine terms.

In 1940, historian William Brailsford Bunting claimed a surgeon had examined the skull and determined that it belonged to a young woman. He suggested it likely dated to the Iron Age, as there were multiple ancient barrows in the neighborhood.

A 19th-century postcard of Tunstead farmhouse, ‘The home of Dickey’s skull.’ Photo: Buxton Museum and Art Gallery

An address to Dickie

In 1863, Dicky got involved in local politics. The people who lived and worked around Tunstead had long reported that Dicky was deeply concerned with the area’s goings-on. Supposedly, he warned of burglary or illness and woke people to alert them to emergencies.

According to accounts, he was deeply protective of the farm. So when the London and North Western Railway company planned a new line which would run through the farm, he was incensed.

To put in the relevant section of line, the company had to build a bridge. The planned construction ran into constant difficulties with the ground, which repeatedly collapsed and sank into the marsh. Finally, the company was forced to build their bridge somewhere else, rerouting the line to avoid the farm. The new bridge was henceforth called “Dickie’s Bridge.”

The incident became regionally famous, inspiring Samuel Laycock, a Lancashire poet of that era. The following is the first section of his poem, printed in the Buxton Advertiser in July 1863:

Neaw, Dickie, be quiet wi’ thee, lad,

An’ let navvies and railways a be;

Mon, tha shouldn’t do soa– its to’ bad,

What harm are they doin’ to thee?

Deod folk shouldn’t meddle at o’,

But leov o’these matters to th’wick;

They’ll see they’re done gradeley, aw know–

Dos’t’yer what aw say to thee Dick?

In his heyday, Dicky was the subject of poems, ballads, and plays. You can’t see him today, however. Sometime around 1977, he was buried in secret by a new owner who did not care for him. The new owner moved away soon after.

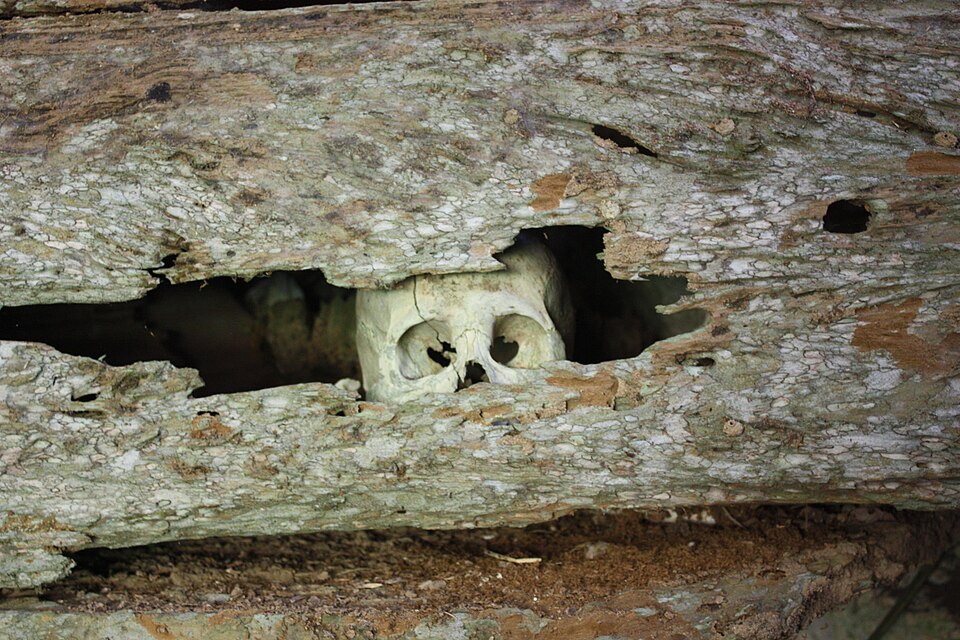

Dicky was in place well into the 20th century. Photo: Clifford Rathbone ‘Goyt Valley Story’ 1955.

Wardley Hall

While it is now home to the Catholic Bishop of Stanford, Wardley Hall was the property of the Downes family starting from 1601. By 1745, both the hall and its owners had fallen on hard times. Troops of the would-be English king, Bonnie Prince Charlie, had sacked the Hall during his invasion of England.

Matthew Moreton, who held a life-lease on the Hall, decided to kill two birds with one stone. He’d tear down the most badly damaged section and install hand looms. He hoped the money from the weaving business would keep him afloat. He did not hope to find a skull, but we can’t always get what we hope for.

When workmen tore down the wall of the old chapel, they found a small chest containing a human skull. It purportedly had a good set of teeth and “a good deal of auburn hair.”

The verifiable timeline is vague. We know at least that Moreton kept the skull in a special niche in the staircase. There it mostly remained, while a local legend sprang up around it. Oral tradition reports the usual skull admonitions: It must not be moved from its place, or screaming will be heard throughout the house.

In 1782, a Manchester antiquary named Thomas Barritt reported that he’d been part of a group that removed the skull one night. Soon afterwards, “such a storm arose about the house, of wind and lightning…!”

Wardley Hall was constructed during the reign of King Edward, on top of an older, 13th-century building. That building sat atop an even older hall from before the Norman Conquest. Photo: Shutterstock

The Saint in the wall

Moreton thought the skull belonged to a persecuted Catholic, executed in the previous century. Local legend offered another, more romantic explanation, involving a nobleman’s murder. But in 1799, the nobleman’s body was exhumed and found to have its head firmly attached.

Wardley Hall was sold to the local diocese in 1930. They favored the martyr theory, and had a specific martyr in mind: Father Ambrose Barlow, now (since 1970) Saint Ambrose Barlow.

Barlow was an auburn-haired priest living and preaching near Wardley during the 17th century. This was a risky business to be in, as waves of Catholic persecution swept the country. Barlow was a cousin of the Downes, who sheltered him and even allowed him to give forbidden Catholic masses in Wardley Hall.

But in March of 1641, King Charles I ordered all Catholic priests out of the country by the end of the month. Barlow stayed and was arrested on Easter Day. At his trial, he did not deny his Catholic faith, but defended his right to practice it. The judge was not convinced. He was hanged, and then, since apparently that was not enough, he was beheaded, quartered, boiled in oil, and had his head put on a pike.

Many locals, including the diocese, believed that Francis Downes had taken his cousin’s head back to Wardley and hidden it in the chapel. Secreting away the heads of murdered Catholics was very much the done thing at the time.

In 1959, the skull went to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London for testing. The physical clues support the Barlow theory: The skull belongs to a man in his fifties, the same age as Barlow, who had been beheaded and piked.

In 1961, the Diocese officially recognized the skull as that of the martyr Ambrose Barlow.

The skull at Wardley Hall. Photo: Chetham Library, Mullineux Collection

The ‘Cult of the Head’

In the folklore of the United Kingdom, the human head and the skull in particular seem to hold a place of special importance. The motif of the severed but conscious head appears over and over across the British Isles.

An index of folk story motifs records tropes like “Return from dead to punish theft of skull,” “Severed head cannot be moved from helmet,” “Severed head of saint speaks so that searchers can find it,” and “Severed head moves from place to place” all come from the region. Then there is the “beheading game,” appearing most famously in the Arthurian Middle English poem, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Some archaeologists and historians think this focus on the skull has deep cultural roots. Classical sources and physical evidence suggest a Celtic “cult of the head.” Ancient Greek historian Diodorus Siculus wrote that Celts would collect the heads of defeated enemies. The ancient warriors would then take the heads home, preserve them in cedar oil, and keep them in their homes.

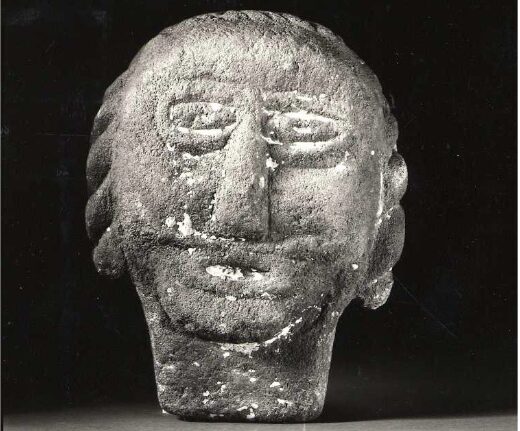

Carved stone heads appear all over Iron Age Celtic sites. These life-sized heads were still being produced in Britain into the 17th and 18th centuries, at the same time all these screaming skulls were showing up.

And they kept showing up — the few I’ve outlined here are only a selection of the most well-documented. We know of dozens more. Perhaps the cult of the head does live on.

This dashing fellow was found in Lancashire in the 19th century, and is believed to date from the Iron age. Photo: The British Museum

‘Alas, poor Yorick’

There’s something rather special about a human skull; it seems to hold a unique fascination. Somehow, one just can’t see Hamlet waxing poetical to a tibia or rib cage.

Severed head historian Frances Larson writes that “Once a fragment of the human body is preserved and kept above ground for any length of time…it develops an identity of its own and tends to resist its own burial.”

She wrote this in relation to Saint Oliver Plunkett, who has a very similar story to Saint Ambrose Barlow. Plunkett’s decapitated head didn’t scream, but it did communicate to the living through the performance of miracles.

The head is the seat of the brain and thus, the intelligence. People forced to survival cannibalism will often avoid eating the head, because even after death, they cannot separate it from a living person. The skull is both an object and a person. Like an object, it’s kept in a place. Like a person, it’s liable to scream if that place is not where it likes best to be.