A team of astronomers in Australia searching for radio flashes from distant galaxies has found something a lot closer to home. The defunct communications satellite Relay 2, out of commission since 1965, is chirping at the Earth in radio frequencies.

A mysterious burst from nearby

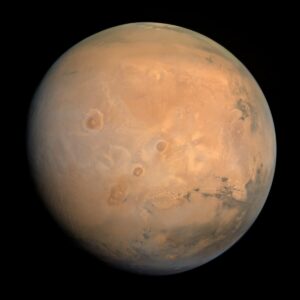

The Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) searches the radio sky for sudden, unexpected flashes. These can come from supernovae or more exotic sources like rotating white dwarfs. But ASKAP is particularly talented at finding Fast Radio Bursts, brief outbursts of radio waves coming from galaxies millions or even billions of light years away.

In a preprint paper released this month, a team at ASKAP reported a signal that looked like a startlingly bright Fast Radio Burst. It lasted the same general amount of time (only 30 billionths of a second) and emitted a broad range of radio frequencies. But unlike Fast Radio Bursts, it seemed to come from right outside the Earth’s ionosphere.

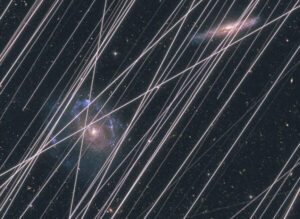

When radio waves travel from faraway galaxies, they interact with electrons floating around in interstellar space. Those electrons slow down low-frequency waves more than the high-frequency waves, causing them to arrive at the telescope after the high-frequency ones. Astronomers call this effect “dispersion,” and it works as a rough proxy for distance. Since we know about how many free electrons there are in every direction, we can calculate how far radio waves must have traveled through those electrons to be delayed a certain amount.

High-frequency radio waves pass through electrons more quickly than low-frequency radio waves. The speed of light is only a constant in a vacuum. Photo: CAASTRO

But for the recent ASKAP burst, there was barely any delay between the high- and low-frequency parts of the wave. The burst came from our own neighborhood.

Radio astronomers have a touchy history with things that look like Fast Radio Bursts but come from nearby. For a long time, mysterious signals called perytons showed up all over the place, until a group realized it was actually the microwave oven in the observatory break room.

Needless to say, microwaves are now kept under strict control at radio telescopes. So what was this new signal?

Tracking down an undead satellite

Reasoning that the only things floating around in nearby space that might release radio waves are satellites, the ASKAP team started searching. They compared the point of origin of the burst to maps of satellites. But the only matching satellite, Relay 2, hasn’t been in operation since 1965.

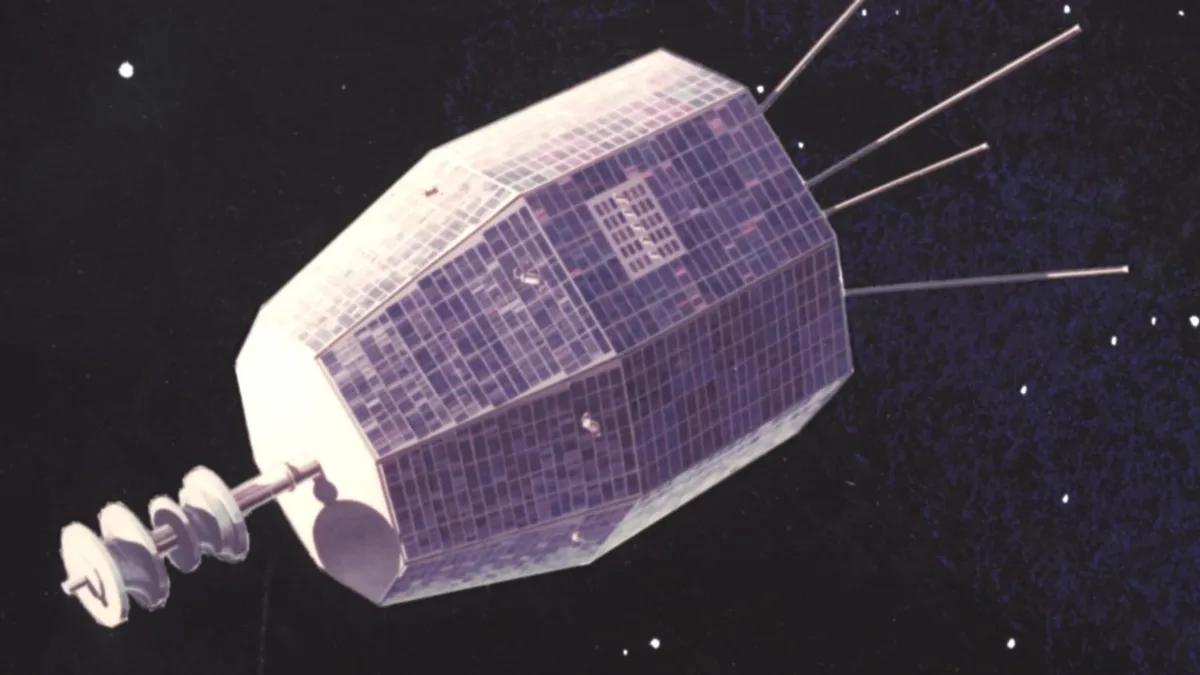

Relay 2 was a NASA telecommunications satellite with a handful of physics experiments onboard, all long since defunct. According to NASA reports, it’s been more than 50 years since anyone has purposefully used Relay 2.

While it’s possible NASA is using Relay 2 secretly, the ASKAP team doesn’t think this is likely. The plans for the satellite are publicly available, and nothing onboard is capable of producing such a short, bright burst.

An artist’s impression of the Relay satellites, launched in 1964. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The explanation

The team proposes two possible explanations for this strange emission. In the first, solar winds slam into Relay 2, building up charge against one plate of the satellite like rocks by the ocean build up salt. When the charge becomes so strong that the scant gas molecules between one plate and another can’t take it anymore, the gas ionizes, releasing a sudden burst of visible light and radio waves. This is called electrostatic discharge. It’s like lightning for satellites.

The other option is that micrometeoroids are slamming into the satellite, creating a cloud of dust and plasma right around the satellite. Then electrostatic discharge can happen even more easily.

It will be hard to tell which of these options is at play without observing Relay 2 over a long period of time. If the radio bursts happen at regular intervals, then they likely come from electrostatic discharge after a buildup. Micrometeoroids, on the other hand, wouldn’t stick to a schedule.

Either way, observing short radio bursts from satellites may be a new way to probe the electric composition of space right outside the ionosphere.