In the late 19th century, settlers pushing into the American Midwest looked up from their newly planted fields to see a black shape covering the sky. The air hummed with the sound of billions of insect wings. Devouring crops, blocking out the sun, and poisoning the rivers and streams: It was as if doomsday had come, and the horseman of the apocalypse was the Rocky Mountain Locust.

The American government feared that successive plagues of grasshoppers would end westward expansion. The frontier farmers and settlers of the Midwest feared starvation. Together, they launched a war against the grasshopper menace.

Settlers burned grasshoppers in an attempt to stem the tide of hungry, buzzing beasts. Photo: Kansas Historical Society

And the locusts went up over all the land of Egypt

For the new settlers of Kansas and the surrounding territory, 1874 needed to be a good year. The westward push had only reached the area twenty years earlier, and many families were planting their first crops.

The past few years had included a series of setbacks, with fires and hailstorms devastating crops, and the ever-present danger of reprisals from the people whose land they’d stolen. But it was a very dry summer, and the farmers anxiously watched the sky for rain. They didn’t think too much about what was hopping about their feet.

Then one hot, hazy day in late July or early August, they looked up to see a veil drawn over the sky. It grew darker and thicker, like a gathering storm cloud, as a thunderous sound filled the air. Lillie Marcks, who was twelve at the time, described how “a solid mass filled the sky. A moving grey-green screen between the sun and the earth.”

Then the locusts descended. Another witness, Mary Lyon, recalled that as they dropped down, it was like a snowstorm, “where the air was filled with enormous flakes.” They covered the earth, four inches deep in places, and visited devastation on anything they touched. Their voracious appetite spared nothing.

A field after the grasshoppers were done with it. Photo: Kansas Historical Society

Biblical destruction

The swarm didn’t just eat the crops; it ate everything. Once the crops were gone, they stripped the leaves from the bushes and trees. When all the growing things were nothing but sticks, the swarm turned to the houses, munching on food stores and anything made of wood. Finally, they literally ate the clothes off people’s backs. The insect’s corpses and excrement polluted the water supply. The swarm was thick enough to stop trains, as mountains of their little bodies, crushed beneath the locomotives, slicked up the tracks to an unworkable degree.

The result was an estimated 200 million dollars in damages across vast swathes of the U.S. and Canada, from Texas to the Northwest Territories.

The newspapers were swarming with stories of the plague. One article in The Donaldsonville Chief compared it to the Great Chicago fire, going on to say that men who woke up rich, ready to harvest their crops, were going to bed beggars.

Regional authorities received piles of letters from settlers begging for aid. One elderly farmer wrote to Minnesota Governor Cushman Davis that grasshoppers had destroyed his crops, and “we can see nothing but starvation in the future if relief does not come in time.”

He was one of many, as a Cottonwood country commissioner reported: “I have in my district many familys [sic] that are about on the verge of starvation.”

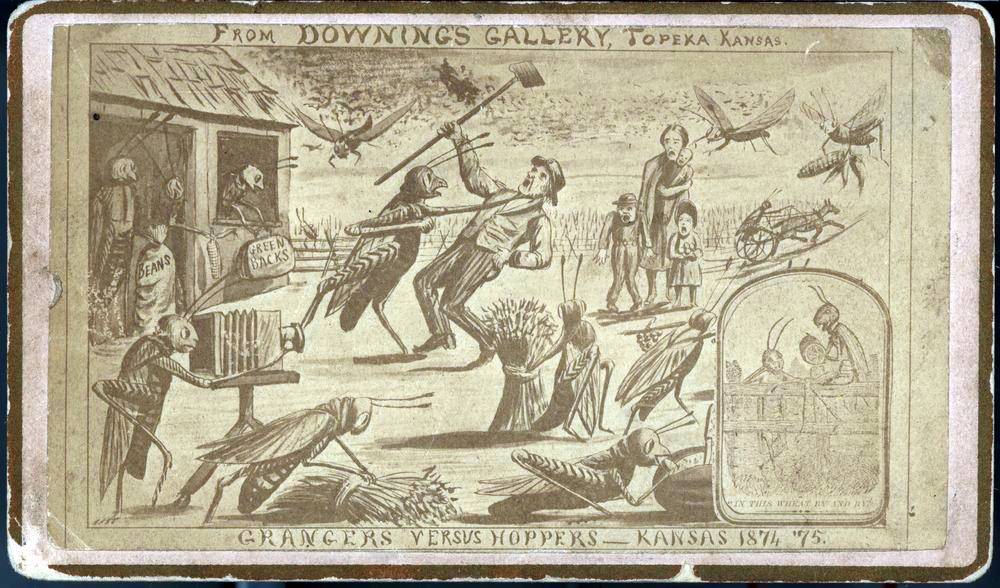

A contemporary cartoon from Kansas showing the struggle between farmers and grasshoppers. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The U.S. vs locust swarm

Across the country, the government organized to protect its starving people, or — if you are a cynic — protect the imperialist project of westward expansion. They also rushed to downplay the problem, fearing that the true scope of the locust plague would deter settlers. As many as one in three of Kansas’ new settlers had packed up and headed back east after that summer, and migration to the Great Plains sharply decreased.

Both private and state aid were distributed. Governor Davis raised $18,959 for relief efforts, and the state government granted a further $5,000 for direct relief. Similar grants were made throughout the affected region, and many philanthropic societies donated clothing to replace the settlers’ locust-eaten garments.

Meanwhile, the settlers themselves tried all they could think of to fight back. At first, they covered their gardens in thick cloth; it was no good, the locusts just ate the cloth. They tried fire, but it had limited effectiveness. Lillie Marcks watched her father and his hired man dig a massive trench and light it on fire, only for the mass of grasshoppers to smother the flames.

Enterprising farmers-turned-engineers invented the “hopperdozer,” a device pulled by horses, and meant to roll over fields catching the locusts. But it only worked on flat fields and was overwhelmed by the scale of the problem. Entomologist Charles Valentine Riley urged people to try eating the grasshoppers, which have been eaten around the world for thousands of years, but it didn’t catch on.

A ‘hopperdozer’ device in the early 20th century. Photo: National Archives and Records Administration

A natural history of the Rocky Mountain Locust

Locusts are a subcategory of grasshoppers. Environmental pressures trigger these grasshopper species to merge into massive swarms. This transformation isn’t just behavioral but physical. Under the influence of the call to swarm, grasshoppers can change color and grow stronger wings, coming together as a huge force that behaves collectively.

The life of a locust is a series of transformations. The Rocky Mountain Locust, Melanoplus spretus, laid its eggs in the dry Rocky Mountains Plateau, emerging in spring without wings. They hopped about voraciously devouring all they could, and when they reached their adult stage, they grew wings and took flight.

Melanoplus spretus was the only North American locust, and the 1874 event was not its first appearance. Smaller-scale plagues had occurred across the region in the preceding half-century. In 1818 and 1819, swarms hit Minnesota and Manitoba, and a year later, one appeared in Missouri. In the 1850s, Texas was hit hard for several years in a row.

But none of these compares to the scale of the 1874 swarm.

This map of the 1874 locust spread shows their breeding area, yellow, and regions they raid commonly (pink) and rarely (green). Photo: Contemporary report by the Chief of the U.S. Entomological Commission

Wrong place, wrong drought

It was a case of bad luck and bad timing for the new Kansas farmers. The exceptionally long, dry summer made perfect conditions for grasshopper eggs. When the many hungry grasshoppers emerged, they found that the drought had withered the plants. A lack of available food triggered their horror-movie style transformation into a ravening horde.

Up to 12.5 trillion individual insects swarmed and took flight. According to one account, the size of the swarm was so great that it blotted out the sun for six straight hours. Modern estimates are that it covered 5,200,000 square kilometers of land.

An introduction to the Missouri entomological reports on the subject wrote that the locust “constitutes today the greatest obstacle to the settlement of much of the fertile country between the Mississippi and the Rocky Mountains.”

When the locusts returned in 1875 — though in comparatively fewer numbers — it seemed the colonial project of western settlement was doomed. In 1877, the Nebraska Legislature went so far as to declare the insect a “public enemy,” which its citizens were now legally obligated to destroy.

But every year, there were fewer locusts. Every year, more crops survived, more farmers came, and the westward push continued. The last confirmed sighting of a living Rocky Mountain Locust was in 1902.

Only a few decades after they were filling boxes and boxes of specimen archives, the Rocky Mountain Locust was gone. Photo: Matt Hayes/Cornell University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

Extinction (we think)

Many factors contributed to the rapid extinction of the Rocky Mountain Locust. But the main cause was likely the large-scale destruction of their eggs. While their range was large, the locusts’ permanent breeding ground was small, only a few thousand square miles. When farmers started turning and irrigating that soil, their trillions of eggs were killed.

Some argue that Melanoplus spretus may still survive in small populations, living and dying in its solitary form. If isolated populations do survive, they’re keeping their heads down. In 2014, the IUCN officially declared them extinct. But they left a mark on American culture, appearing in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s book, On the Banks of Plum Creek.

Few mourned the loss of the Rocky Mountain Locust. But their extinction was certainly a blow to the northern curlew, which lived off the locusts during their annual migration. These once-common birds are now also presumed extinct.

Funnily enough, the de-extinction startups aren’t suggesting they bring back the Rocky Mountain Locust. I get it, but on the other hand, 12.5 trillion locusts might give America an exciting, new problem. Sometimes, that’s the best you can hope for.