Every year, mountain rescue teams from the Rockies to the Scottish Highlands issue the same warning: Adventurers should be self-reliant and responsible for their own safety. The message usually follows another late-night helicopter evacuation of a stranded hiker.

As digital tools have seeped into the outdoor world, paper maps and compasses have slipped out of many backpacks. For confident navigators with backup batteries and redundant systems, that’s not necessarily a problem. But for those less skilled with aligning digital navigation with the land in front of them, relying solely on a smartphone or GPS can turn from convenience to liability.

Online guidebooks and navigation apps have reshaped long-distance trails in the United States, encouraging some hikers to outsource decision-making to their devices. At times, the results are comical: Hikers who walk a few feet off the path because that’s where their GPS insists the “real” trail was. At other times, wayward digital advice becomes dangerous. In Scotland, people have followed Google Maps straight into precarious terrain.

Now with artificial intelligence (AI) increasingly offering to plan holidays and travel itineraries, some travelers are turning to AI to plan their wilderness adventures. This summer, veteran Swedish adventurer Mikael Strandberg was trekking in Kyrgyzstan’s Karakol Valley with his two daughters when he came across two young men who he learned had planned a 7 to 9-day trek entirely using AI.

Strandberg in Kyrgyzstan. Photo: Mikael Strandberg

Trek planning with ChatGPT

The two men, who were from Saudi Arabia, wandered into Strandberg’s camp late one day, as darkness fell. The first indication that something was off was when one of them erected a very small tent.

“They had these tents where they couldn’t stretch out, that you buy your kids when you’re going to go down to the beach. And that was a suggestion from AI,” Strandberg explained.

“They didn’t find the brand they were looking for,” he continued, “so they took something that looked like it. It also became apparent that their fuel allocation had been recommended by ChatGPT.”

Strandberg’s camp in the Karakol Valley. Photo: Mikael Strandberg

“They asked AI, how much fuel do they need to take for nine days, because we can’t carry too much. Okay? So AI thinks, ah, we will help them by telling them what they want to hear,” said Strandberg.

“They had two small gas bottles for nine days,” said Strandberg, who was not judgmental but concerned about their welfare. “They hadn’t even been able to pull out the stand on the stove that you screw on…So they put a pot on it…in the morning, and obviously it fell over.”

Overloaded and undercooked

Further conversation revealed the two men had done a few day hikes, but never a multi-day hike in a remote area. So when AI suggested meager food rations and unnecessary items to weight down their packs, they were none the wiser.

“They had something like 25 to 30 kilos of weight in the backpack…[but] they brought five kilos of food between two people, including snacks, for nine days.”

Photo: Mikael Strandberg

They also had no paper maps (they’re hard to find in these post-Soviet regions) or navigation skills, relying on AI and GPS, which had plotted routes that Strandberg suggested were ill-advised. When back home, the 63-year-old Swede tried out ChatGPT for route planning himself to test out its accuracy.

“What I got back was just rubbish,” he said. “So I asked my AI buddy, why are you doing this, this is dangerous? He didn’t answer immediately because he was offended. And then he came back. ‘I just wanted to make you happy. I just gave you something which was quite close.’ It was 25 kilometers off. So you have to be able to ask the right questions.”

A worked example

Unlike the Saudis’ trek in remote Kyrgyzstan, many trails are well documented online. When I asked ChatGPT some basic questions, its answers were surprisingly close to my actual experience. This suggests that the usefulness of AI depends heavily on the trail and the trekker.

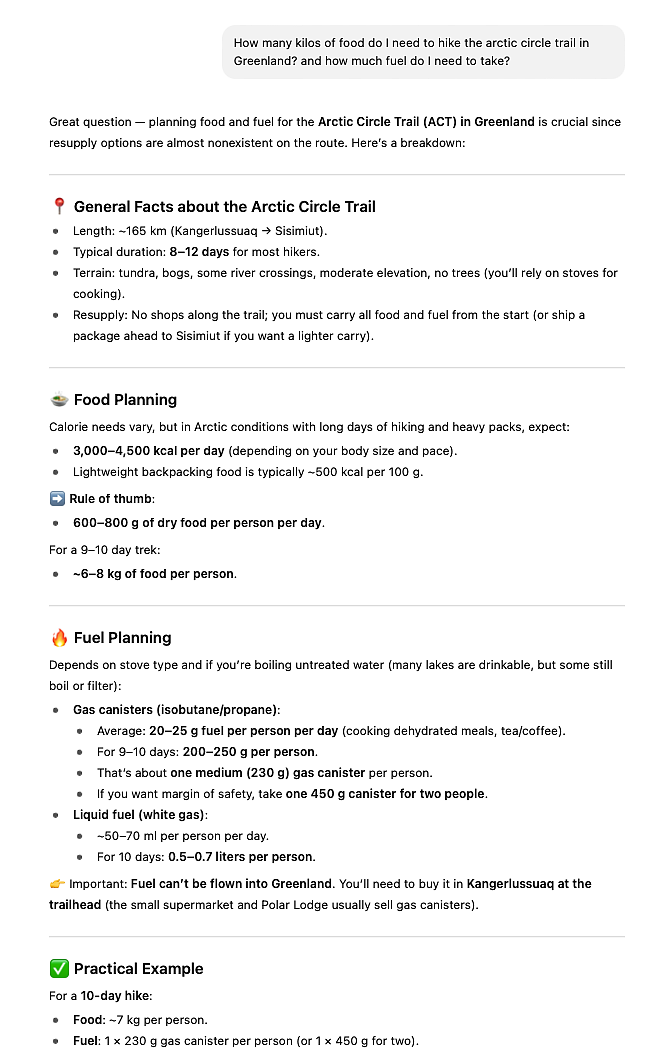

I tested out ChatGPT by asking it the following question: How many kilos of food do I need to hike the Arctic Circle Trail in Greenland, and how much fuel do I need to take? In a rather long-winded answer, AI estimated that I would need 6-8kg of food and one 230g gas canister.

When I hiked an extended version of this trail over 11 days in 2023, I took 7kg of food and a 230g gas canister, and a smaller spare. In this case, ChatGPT’s advice was pretty good. Perhaps with the right questions and route, AI is a useful starting point as a planning aid for those experienced enough to discern fact from fiction.

A cautionary tale

Returning to Kyrgyzstan, when the two Saudi men left camp, they struggled to cross the nearby river, and so one of Strandberg’s teenage daughters helped them across. The Swede had bid the two Saudis farewell, pointed them in the direction of the nearest road, and suggested they rent horses and a guide. Perhaps not surprisingly in this tale, they had little money on them to pay for guides and horses, having entrusted ChatGPT to plan the trip finances.

The veteran Swedish adventurer does not know what became of the two men, and they may well have safely found their way back to civilization with a few tales to tell at the local watering hole. But his experience with these two novice hikers serves as a cautionary tale on the potential risk of handing over adventure and expedition planning to AI if you have little experience in the field.